A “MASLENITSA” PATTERN FROM ARKHANGELSK OBLAST’

Early 20th century. Village Cherevkovo on the Northern Dvina. Wood carving and wood painting

Sleighs like these – colourful and bright, with fancy painting – were produced in villages all along the Northern Dvina specially for youth who would do downhill sledding during Maslenitsa, an Eastern Slavic festival of spring and sun. These festive sleighs are made of wood and are firmed with iron strips on their edges. They are adorned with three squares of relief carving and decorative painting, where shades of red and green serve as dominant colours.

THE GENTLE BLOSSOMING OF NATURE IN SPRING (THE NIZHNY NOVGOROD OR THE VOLOGDA GOVERNORATE)

Nizhny Novgorod or Vologda Governorate. Second half of 19th century. Lace-making

Masters of lacemaking from Nizhniy Novgorod and Vologda tended to create a colourful composition of a background, as can be seen on this lace edging that dates from the first half of the 19th century. Here lush blooming snow-white bushes almost grow out from the setting coloured with ochre shades. This way, using their own specific methods, lacemakers managed to create expressive, distinctive imagery. The sumptuous, sophisticated pattern made by intertwined flowering branches reflects blossoming spring nature associated with snow-white florets of guelder roses, rowans, apple trees, and other plants.

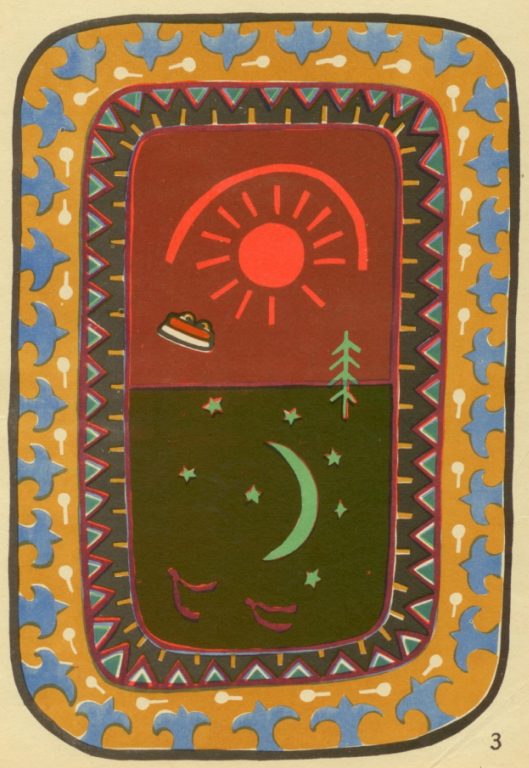

THE ORNAMENTATION OF A TROPHY FOR THE CHUVASH SPRING COMPETITION

Fancy weaving is one of the most widespread and ancient forms of traditional arts in Chuvash culture. Until the first half of the 19th century, the range of most popular articles produced in this technique included belts (the Upper Chuvash), special head covers known as surpans (the Lower and Mid-Lower Chuvash), headwear swathes, coverlets, rugs, and gift surpans sölkö. Sölkö served as a prize for winners of competitions that took place during Akatuj – a festival of earth and plough.

The ornamentation of weaved articles was based on geometric and floral patterns, such as “tree of life,” “firmament,” “luminaries.”

THE PROCESSION OF SPRING AND AUTUMN SUNS IN PATTERNS FROM THE OLONETS AND TVER GOVERNORATES

Second half of 19th century. Embroidery. Olonets Governorate province

Female peasant clothes of Northern regions are particularly colourful and rich decorated. Ornamental compositions here are based on the repetition of a female figure that holds birds in its lifted hands, a stylised female figure in its centre, and an ornamented figure with a rhomboid head and birds inside. Geometrical human figures seem to “grow” out of rhombi and crosses that symbolise fertility and the feminine core of nature. According to folk beliefs, rhombi represent the Sun circle, while a rhombus with a cross and female figures might symbolise the life-giving nature of the Sun. Supposedly, the interchanging images of “maidens” and “mothers” supplemented with floral elements metaphorically represent the cycle of seasons and the movement of the Sun during the September and March equinoxes. As for the technique, masters of the Russian North preferred counted thread method and half cross stitches that allowed creating so-called “paintings” (i.e. very dense compositions) without removing threads from fabric. Masters would embroider silver-shaded canvas with red threads, working tiny stitches horizontally, vertically, or diagonally, this way outlining the pattern. Then they would mark the inner part of the ornament with horizontal and vertical stitches, thereby creating small “squares” and later filling them chequerwise with crosses. This way masters produced dense ornaments comprised of many small elements.

Second half of 19th century. Embroidery. Tver Governorate province

The centre of this three-part composition is formed by an anthropomorphic figure. It is flanked by two female figures with birds in their lifted hands; there are also several birds placed inside the figures. Supposedly, the interchanging images of “maidens” and “mothers” supplemented with floral elements metaphorically represent the cycle of seasons and the movement of the Sun during the September and March equinoxes. The location of ornaments on everyday items is always defined by their form and purpose. Here, the female figure becomes a conceptual core of the towel’s ornamentation, and the two horsewomen that flank it complete the symmetrical composition. Such three-part patterns where all figures are depicted with raised hands might be referred to as “the welcoming of spring.” The idea of light (which symbolised the Universe in Medieval beliefs) is represented through various solar symbols that surround the female figure. Each ornamental motif in the towels’ decoration is an integral symbol, but being placed together, they create a complex artistic message. For instance, a three-part composition of towels’ edges is frequently accompanied by an ornamental frame with images of “maidens,” while its top and bottom are complemented with various small elements, such as plants, birds, and solar symbols that are being reversed with respect to each other. This sequence might resemble a prayer repeated several times, or a spell for a rich harvest. As for the technique, masters of the Russian North preferred counted thread method and half cross stitches that allowed creating so-called “paintings” (i.e. very dense compositions) without removing threads from fabric. Masters would embroider silver-shaded canvas with red threads, working tiny stitches horizontally, vertically, or diagonally, this way outlining the pattern. Then they would mark the inner part of the ornament with horizontal and vertical stitches, thereby creating small “squares” and later filling them chequerwise with crosses. This way masters produced dense ornaments comprised of many small elements.

First half of 19th century. Embroidery

A rhomboid grid with four-leaf rosettes inside each square form the core of this item’s composition. The edging is filled with repeating anthropomorphic motifs. Supposedly, the interchanging images of “maidens” and “mothers” supplemented with floral elements metaphorically represent the cycle of seasons and the movement of the Sun during the September and March equinoxes.

THE IMAGERY OF SPRING SUN IN THE EDGING FROM THE ST. PETERSBURG GOVERNORATE

Second half of 19th century. Embroidery

The upper ornamental band features a repeat design of a peacock and female rider holding birds in upraised arms, with solar rosettes and minor birds as subsidiary motifs. Arranged in the middle band are large birds with one wing raised, flanking a formalized female figure. The repeat motif of the outer edge is a blossoming tree (the Tree of Life motif?) set between two confronted horses with onventionalized ‘bird boats’ fixed on their backs; on either side of the tree opposed zoomorphic subjects (wolves?) are set.

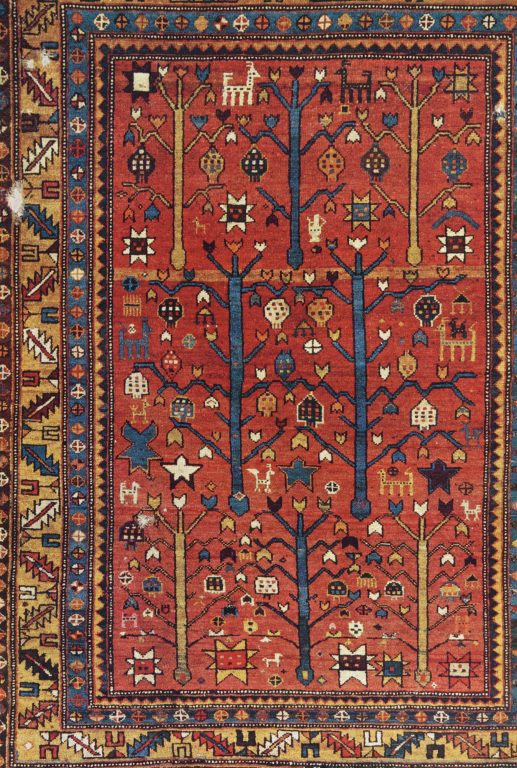

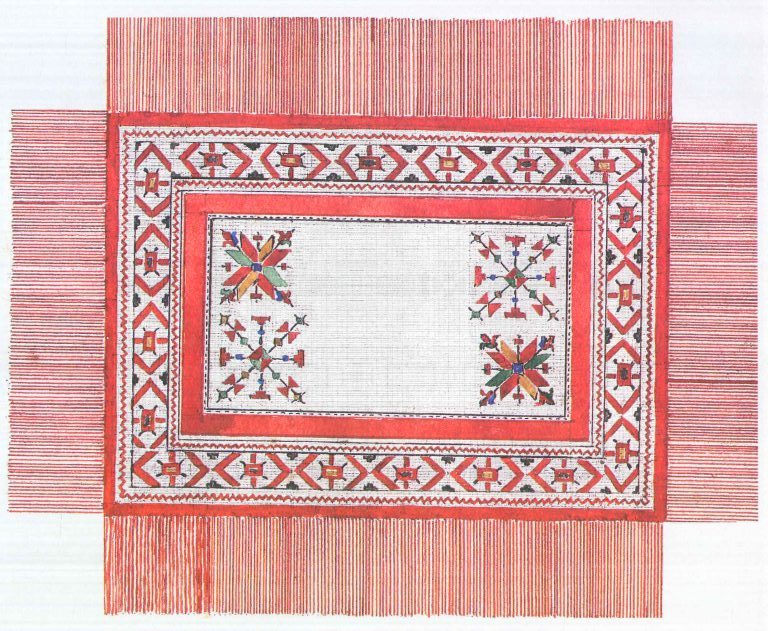

THE SPRING BLOSSOMING OF GARDENS IN DAGESTANI PILE CARPETS

The art of rug making goes back centuries in Dagestan. The production of carpets developed alongside with sheep farming. Tufted (pile) carpets are the most popular type of rugs from Dagestan that is known far beyond this region. It is the main type of rugs produced in the Lezgin, Kurin, and Tabasaran areas of Dagestan. Although Dagestani pile carpets are frequently called by a common name “Dagestan,” or “Derbent,” there are in fact many kinds of rugs that differ in their knot density and ornamentation. For instance, there are eight types of pile carpets in Southern Dagestan alone. Rugs can be classified in several groups based on the technology of their making that determines the length and density of pile. Usually rugs with a very high knot density have low pile (“akhty,” “mikrakh”), and those with a low knot density are defined by high pile (“tlyarata,” “dzhengutaj”). However, there are also carpets that combine both a high knot density and relatively high pile (“rushul,” “kazanice”). Low pile rugs are very elastic and soft; the higher pile a carpet has, the stiffer and firmer it becomes.

Ornamental motifs of Dagestani pile rugs are characterised by the large variety of compositional elements, the diversity of colours, and very rich patterns. A Dagestani carpet is a peculiar reflection of wildlife: in its decoration one can see gardens blossoming in spring, mountains in sultry summer mist, or an autumn abundance of fruits. Ornamental motifs include images of plants, animals, and housewares. Patterns and colours depend on aesthetic values of mountain women, specifics of local culture, and the environment. A soft cherry-red background is decorated with white and pink “almagjul” – apple blossoms, rounded “patnusi” – trays with grape bunches, figured “changi” – leaves, “kushgjul” – a nightingale and a rose, and many other elements. Patterns “ketser,” cats, and “karchary” that depicts horns of a black-tailed gazelle supplement the overall ornamental composition.

Patterns “rushul,” “mecca,” “kaaba” were especially popular in the past: their names refer to the great impact that Islam had on the region. Such terms as “mecca” or “kaaba” (a mosque), “mihrab” (a prayer niche), “lamp” (a lampion) indicate that rugs had a ritual, religious function. The ornamental motifs lost many of their characteristic features when prayer mats had fallen into disuse. Yet, some elements important for the balance of a composition persisted, for example columns of “mihrab” that emphasise vertical lines of a carpet and adorn its edging.

Works cited:

- “Russian Folk Wood Carving and Painting from the Collection of the Zagorsk State Historical And Art Museum-Reserve”, О. Kruglova, 1983

- Album “НFolk Painting on the Northern Dvina”, О. Kruglova, 1987

- “Folk Ornament in the Design of Art Products. Bobbin Coloured Lace”, N. Klimova, 1993

- “Chuvash Folk Art”, E. Medzhitova, A. Trofimov, 1981

- “Russian Folk Embroidery: Pictorial Motifs”, G. Durasov, G. Yakovleva, 1990

- “Decorative Art of Dagestan”, D. Chirkov, 1971