Patterns in Udmurt Culture

The Udmurts are a Finno-Ugric people who live in the very centre of Russia, between the rivers Kama and Vyatka. 410 000 Udmurts reside in the Udmurt Republic alone, while in total, there are over half a million people of this nationality in Russia. The Udmurts are not a small-numbered people, yet the Udmurt language and culture deserve considerable attention and research.

Traditional patterns and their elements serve as a live chronicle of folk rituals, so their investigation might help understand the life, habits, and customs of the Udmurts.

Researchers find the origins of Udmurt ornaments in insignias and signs of property. The most ancient insignias were painted on bodies: they helped distinguish between members of different clans. Such symbols also had a protective function, as they connected living people with their deceased relatives. The signs of property covered different items that belonged to a clan. Modified insignias and signs of property gave rise to motifs of traditional ornamentation.

Toleźo: The Ornamental Symbol of Udmurtia

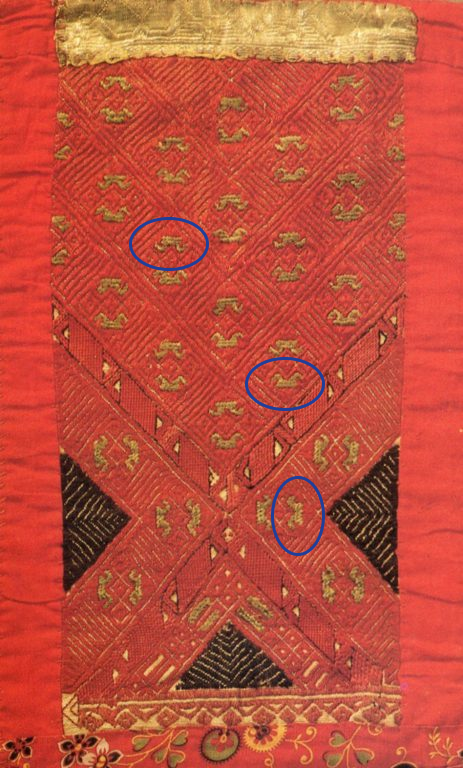

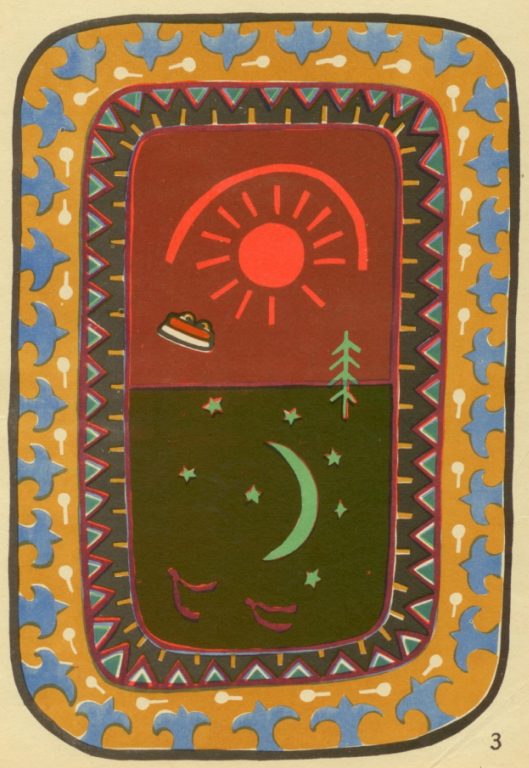

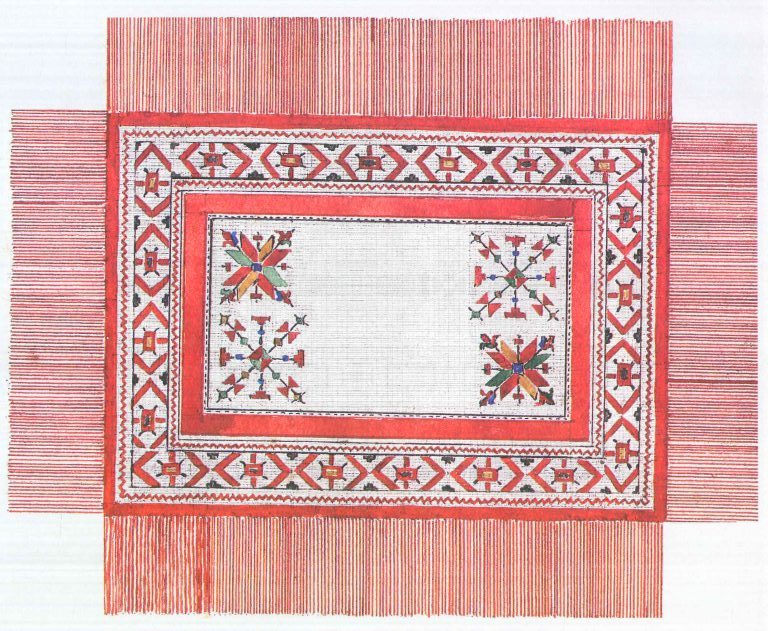

Perhaps the most well-known and recognisable symbol of Udmurtia is a sign called “toleźo,” which means “lunar.” This sign decorates state symbols of the Udmurt Republic, such as the flag and the coat of arms. The eight-pointed star of “toleźo” is an ancient amulet sign. Many peoples of Europe and Asia have similar signs, yet in Udmurt culture, it has a special role.

In the Udmurt language, the word “toleźo” means “lunar,” or “crescent.” Four phases of the Moon correspond to four stages of human life: birth, maturity, ageing, and death. This symbolism is reflected in the pattern: each two points of the star are combined together, thereby creating four rays.

The Meaning of Toleźo in Marriage Rituals

Not any everyday item would be adorned with “toleźo,” as the pattern had a special meaning in the decorative arts of the Udmurts. Wedding clothes had the richest ornamentation. The Udmurts believed that during the wedding ceremony, a girl could be attacked by evil spirits, while ornaments on clothes could protect her against them.

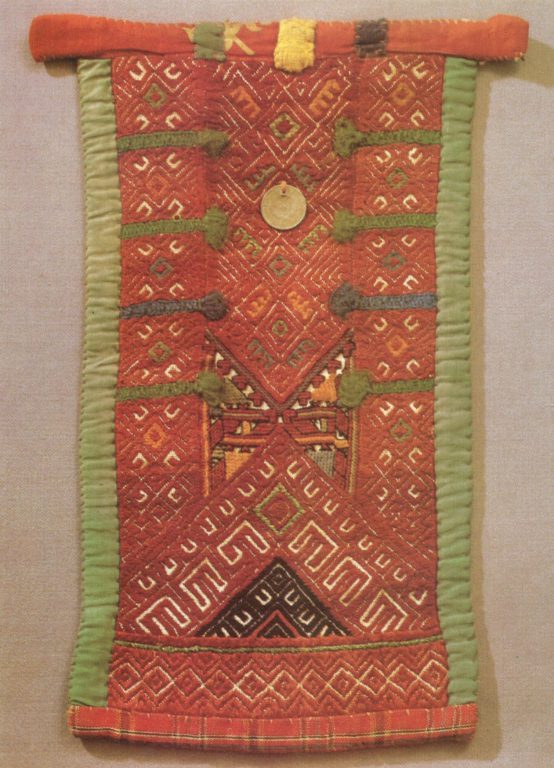

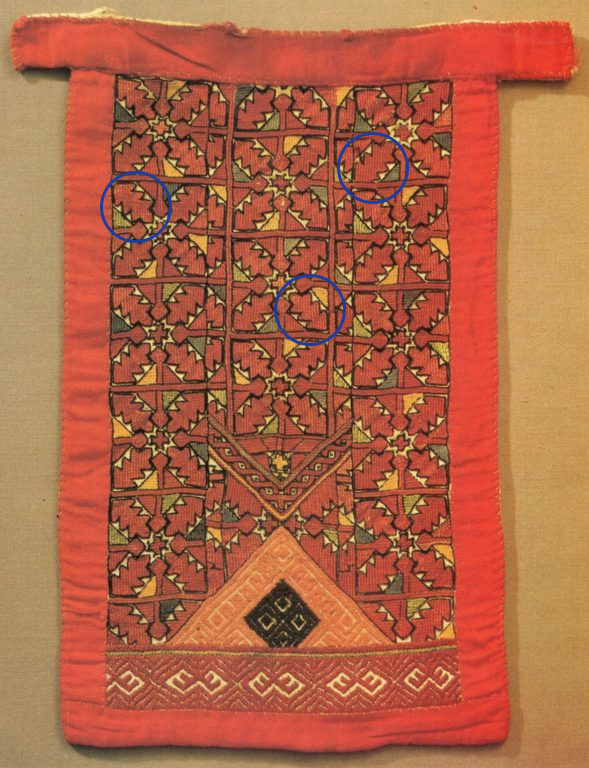

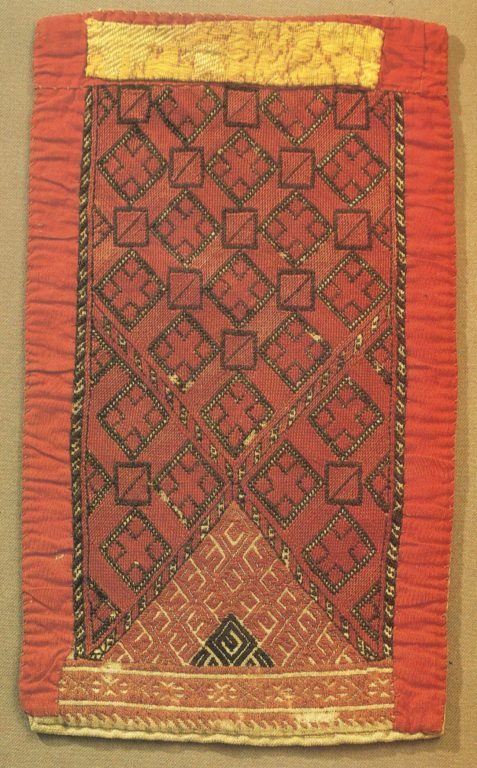

In Udmurt mythology, the Moon is likened to a woman or a mother, so toleźo was the basic pattern in the decoration of a “kabaći,” a female wedding chest apron.

A kabaći was an integral part of the bridal costume. A girl would put it on after she moved to the bridegroom’s house and changed her maiden clothes to woman dress.

In the context of marriage rituals, a red toleźo pattern on a kabaći served as a symbol of fertility. When a girl got married, she started a new period in her life and prepared to become a mother.

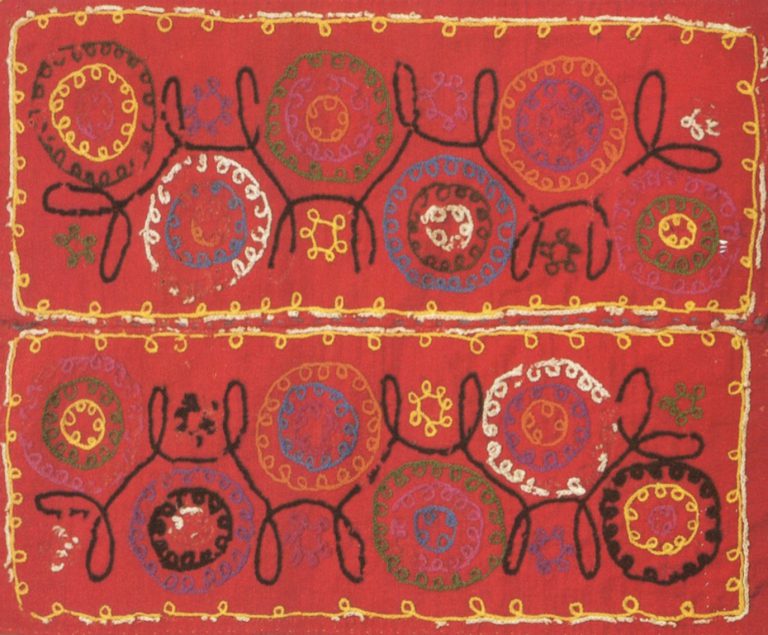

So this ornament has much to do with the idea of protection and procreation. For instance, after a girl got married, she would put on a ćalma – a long towel with decorated edges that served as headgear. Adorned edges of the cloth covered the lower area of a girl’s back, thus the towel symbolically protected the body part that was particularly important for a prospective mother. Women wore ćalmas for the rest of their lives and claimed that without head towels, their backs were “embarrassed” and “not protected.”

Girls started to prepare their dowry from a very young age. Bridegroom’s relatives carefully observed wedding items and gifts made by a girl and assessed her skills in weaving and embroidery. It was important to “protect” the girl’s skills against the evil eye: for that purpose, all items were supplemented with a “ćuk” – a small tassel made of multi-coloured threads and pieces of fabric. The more ćuks an article had, the more skilfully it was made.

The toleźo pattern also decorated festive shirts that a girl would prepare for her future husband as a wedding gift; female festive head towels; and back bags (nypjetah) for carrying babies.

The Most Important Elements in Udmurt Ornamentation

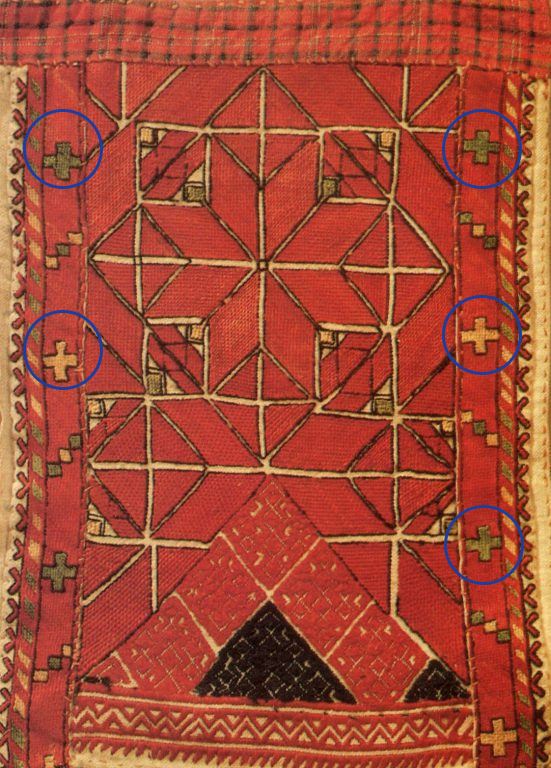

1. Kalmez Pyžy — a Kalmezian Pattern

Kalmez pyžy is a cross symbol. Supposedly, the cross initially was a clan sign of the Kalmezy, a regional group of the Udmurts who lived along the river Kilmez and its tributaries. The Kalmezy settled in the south and the east and later formed a sub-ethnic group of Eastern Udmurts. However, the cross sign gained a prominence among the Udmurts who lived in the north, too.

2. Valo-Valo — a Two-Headed Horse, a Solar Symbol

The image of a two-headed horse has much to do with the cult of the Sun. In Udmurt folklore, there is frequent reference to winged flame horses emerging from water. Heads turned towards different directions symbolise sunrise and sunset.

Along with toleźo and some other patterns, valo-valo referred to the upper world ruled by Inmar – the king of gods in the Udmurt pantheon.

3. Pužym — Pines/Spruces

The Udmurts lived in a wooded area, so trees played an important role in their rituals and beliefs. The cult of a spruce, a pine, and a birch proliferated the most: each of these trees was associated with gods from the Upper, the Middle, and the Lower worlds.

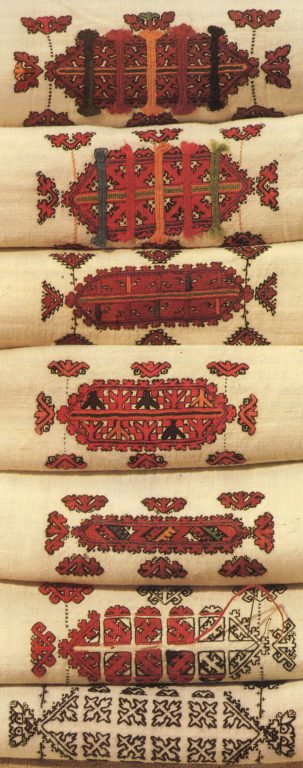

4. Pispu Pužy — the Tree of Life / the World Tree

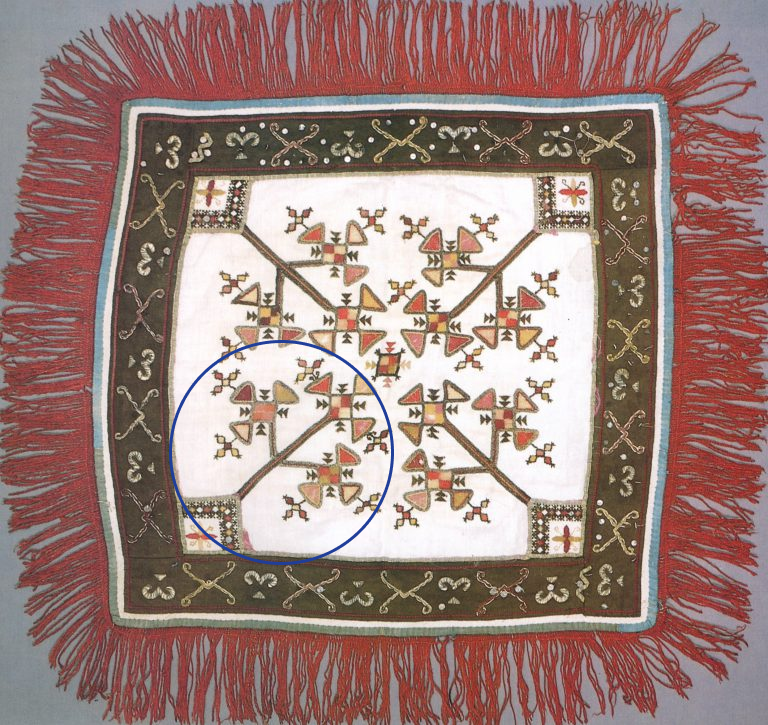

The world tree that connects the Upper, the Middle, and the Lower worlds is a common symbol in many cultures. In Udmurt embroidery, patterns that referred to this concept decorated the edges of a sjulyk, a type of a female head cover that young women put on after they had got married.

5. Ćõž Burd — Duck’s Wings

A duck is another important character in Finno-Ugric mythology. People believed that the duck dived into the pristine ocean and brought in its beak a piece of soil that later developed into earth. A ćõž burd symbol and its modifications are another widespread motif in Udmurt embroidery that refers to duck’s wings.

The Technique of Ornamentation

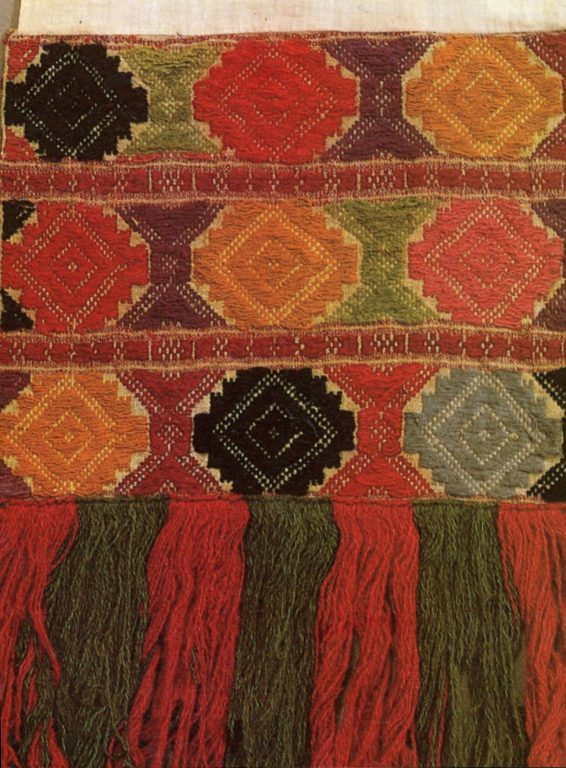

The Udmurts decorated their items with ornaments made in different techniques. Ancient embroidery that adorns chest aprons, head covers, and sleeves is an example of a counted-thread satin-stitch method that is similar to some techniques used in rug making. This method allows making raised patterns that cover the whole surface of an article, so the initial background of fabric cannot be seen. Such ornaments frequently were made without any templates or embroidery hoops.

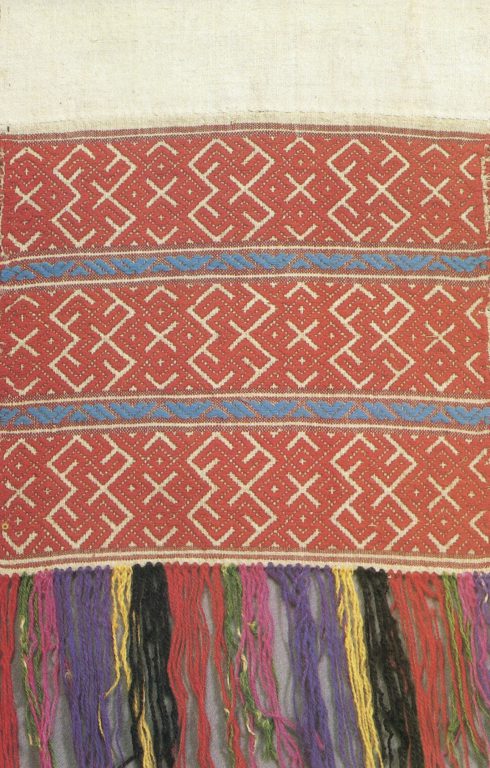

There are several types of the counted-thread technique used in Udmurt embroidery: they include weaving stitch (Russian: nabor), cross-stitch, and satin-stitch. Yet, in the 20th century, free-style embroidery also became quite popular. Udmurt embroiders used 20 different types of stitches.

In the decoration of more modern articles such as muresaz’ aprons, simplified appliqués made of manufactured textile substituted the original embroidery. Yet, sometimes items were also adorned with multi-coloured yarn.

There are two main groups of the Udmurts: the Northern and the Southern ones. They differ in their clothes, for instance in colours they use for decoration. The Northern Udmurts prefer soothing tones and combinations of white, green, and red; red and blue; or blue and brown. The Southern Udmurts use more colours and shades, for instance, bright pink, green, yellow, or orange.

The abundance of embroidery is a distinctive feature of the Northern Udmurt clothes. The Northern Udmurts preferred straight and diagonal stitches with outlined contours. The main colour of their embroidery is terracotta red, but patterns’ edges are always outlined with black threads. Some pieces were also adorned with blue, yellow, and green threads.

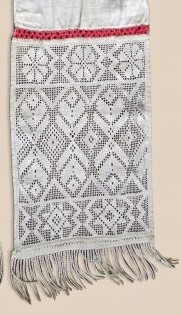

The Northern Udmurts also use such types of stitches as stem stitch, blanket stitch, weaving stitch (nabor), counted satin stitch, cross stitch, braid stitch, perevit’ (openwork technique), and “painting” (Russian: rospis’, a kind of running stitch).

The Kalmezy used a unique technique of embroidery based on removing threads from the warp and/or the weft of a piece of fabric. It is a type of drawn thread work, when the barelaid warp or weft threads are embroidered to create patterns. It decorated hems of dresses, head towels, and sleeves.

Since the late 19th century, the Southern Udmurts tended to use a cross-stitch technique in their embroidery. It adorned chest and regular aprons, towels, and carpets. In some regions, the cross stitch replaced other types of stitches and became the most widespread technique. The cross-stitch embroidery frequently copied Russian ornaments that the Udmurts saw in albums or in traded textile.

Over time, fancy weaving displaced embroidery in the clothes of Southern Udmurts. The most popular techniques included pickup weaving, slit-tapestry weaving, brocade weaving (also known as discontinuous supplementary weft pattern weaving) and a similar method called perebor that differed in the number of shaft bars used. Perebor allowed weaving an ornament in any area of fabric and combining different patterns and colours.

In weaving, patterns are made with the help of coloured yarn. Weavers either got wool from domestic sheep or bought it from traders. Since the 1930s, the Udmurts started to use cotton threads, which they called “dostal” or paper threads, along with yarn.

Works cited:

1. Belitser V. N. The Folk Costume of the Udmurts [in Russian]. Materials on Ethnogenesis. Moscow, 1951.

2. The Udmurt Embroidered Clothes of the 19th – 20th cc. [in Russian]. Ed. by E. N. Kotova. Leningrad, 1987.

3. Kryukova T. A. Visual Folk Art of the Udmurts [in Russian]. Izhevsk-Leningrad, 1973.

4. Lebedeva S. H. Udmurt Folk Embroidery [in Russian]. Izhevsk, 2009.

5. Molchanova L. A. Udmurt Folk Costume (The History and Symbols) [in Russian]. Izhevsk, 2006.

6. Semenov V. A. Udmurt Folk Ornaments [in Russian]. Izhevsk, 1964.

7. Tokareva M. The Toleźo Pattern as an Ornamental Symbol of Udmurtia [manuscript of an article; in Russian], and the description of items with Udmurt patterns (materials shared by the National Museum of the Udmurt Republic named after Kuzebay Gerd).

8. Udmurt Pužjus / Udmurt Patterns [in Udmurt; in Russian]. Ed. by E. D. Klevtsur. Izhevsk, 1994.

Editors of this article: Elizaveta Berezina, Valentina Bogdanova.