The Return to the “Russian” in the Art of the 19th – Early 20th cc.

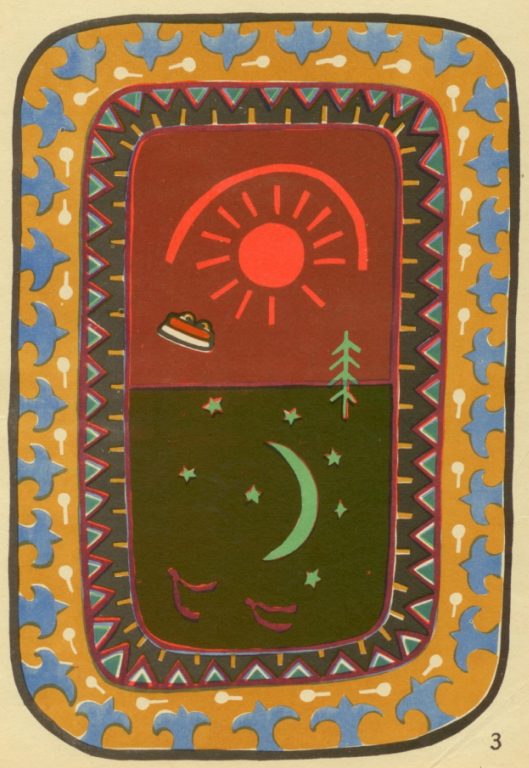

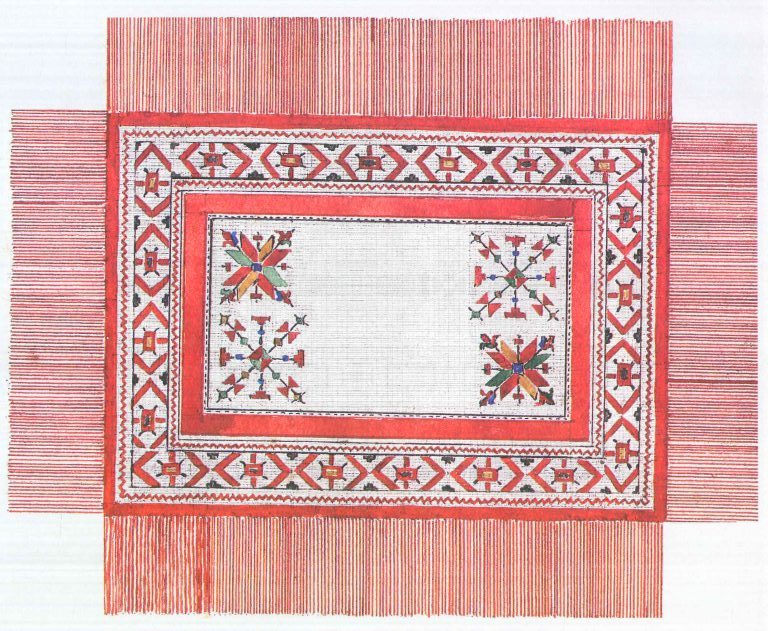

The search for national origins and identity in culture was the distinguishing feature of nineteenth-century art in many European countries. In Russia, the growth of national consciousness was spurred by the victory over Napoleon in 1812. The interest of educated elites in the history and culture of Ancient and Muscovite Rus’ with its architecture and applied arts contributed to the formation of a new, national-romantic taste. The “Russian style” with its adoration for the culture and folk crafts of Rus’ before it was modernised by Peter the Great grew on this basis. Architecture and applied arts inspired by this style reproduced motifs of peasant embroidery, ornaments of ancient manuscripts, and traditional painting.

After Alexander III came to power, the “Russian style” de-facto became an “official” art movement. The Russian Academy of Arts adjusted its programmes to the taste of the Emperor; more attention was paid to the history of pre-Petrine Rus’, and pieces made at the request of the royal court provided guidelines for Russian artists and architects.

The “Russian style” gave rise to the Neo-Russian (Russian Revival, or National Romantic) movement within the Art Nouveau style of the late 19th – early 20th cc. Its characteristic features are the generalisation and stylisation of traditional motifs, plasticity, and theatricality. Residences of Abramtsevo and Talashkino were important centres that supported the development of this style. There were art clubs that united artists, musicians, litterateurs, and theatre practitioners who admired folk culture.

The “Russian Style” in Enamelling of the Second Half of the 19th – Early 20th cc.

The spread and development of the “Russian style” coincided with the revival of enamelling. Vitreous enamel with its rich colours fully matched the style’s passion for carved decorations, which stemmed from a distinct movement in the architecture of the 17th century known as Uzorochye (which literally means “patternwork”). The abundance of decorative elements, fancy ornaments and unusual compositions were the most characteristic features of the Uzorochye.

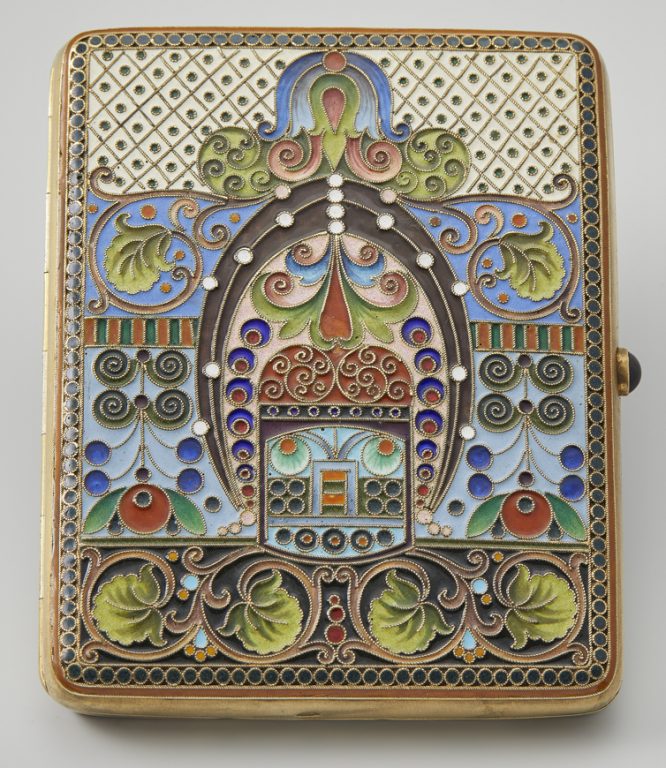

Throughout the second half of the 19th and early 20th cc., various jewellery brands in Moscow used enamel to decorate accessories, everyday items, and furniture. Making sketches for their pieces, designers drew inspiration from folk arts. They decorated their works with abstract figures, spiral swirls, stems, fantastic flowers, and geometric patterns, such as squares with grids and dots inside.

Items made in the “Russian style” replicate not only ornaments, but also the shape of objects of ancient Russian and folk arts: dippers and salt cellars, jewellery boxes that looked like ancient caskets or chests. Such articles were decorated with elements typical for the pre-Petrine era, for instance floral patterns with swirling stems, flower garlands, or geometric patterns that were borrowed from peasant embroidery and woodcarving.

The Revival of Enamelling in Russia: The Firm of P. A. Ovchinnikov

To a large extent, the revival of enamelling in Russia was spurred by the activity of Pavel Ovchinnikov, who produced items of gold and silver in his jewellery factory opened in 1853 in Moscow. His craftsmen worked with all jewellery techniques, but he earned his fame selling polychromatic enamels. The brand of Ovchinnikov offered articles made in such techniques as cloisonné, champlevé, and plique-à-jour. The factory also produced painted (pictorial) enamels, including paintings on skan’ and relief surfaces.

Ovchinnikov’s enamels of the 1860s – 1880s exemplify the beauty of the traditional Russian Uzorochye. Grids, rosettes, jagged figures, images of birds (cocks), and floral patterns copied ornaments from ancient books, handwritten “Antiquities of the Russian State” by Fyodor Solntsev, and folk art objects of the Pre-Petrian period. Such ornaments adorned rizas (revetments) of icons, jewellery boxes, cigarette cases, chests, salt cellars, dippers, tea glass holders, and jugs.

Images of roosters adored by many artists of the “Russian style” decorated various items produced by Ovchinnikov’s firm. Geometric and abstract figures in combination with fantastic blooms, carved leaves, and stylised flower rosettes were characteristic features of the Neo-Russian style.

In later products of the firm made at the turn of the 20th century, geometric ornaments gave way to lush, brightly coloured flower garlands made in the combined skan’-and-enamel technique. Floral patterns with a flower bud in its centre decorate the lid of this cigarette case. Curling stems filled with pearls, luxuriant leaves, circles and skan’-made swirls frame the composition.

The Capital of Enamel Art: The Firm of I. P. Khlebnikov

Ivan Khlebnikov, who opened his firm in Moscow in 1870-1871, also considerably contributed to the development of the national style. His firm that focused on casting, chasing, and carving produced enamels, too. Workers of Khlebnikov’s firm also borrowed patterns from folk arts. They decorated their products – polished and chased teapots, tea glass holders, various dippers and cigarette tins – with rosettes, grids, and flowers.

Khlebnikov’s products were often adorned with text – proverbs or adages written in Vyaz’ (a type of ancient decorative Cyrillic lettering). The central area of this sugar bowl contains the following text (written in Old Russian): “A TASTY PIECE WILL NOT CLOY, NOR… (incomprehensible) A GOOD FRIEND WILL PALL.” Floral and geometric patterns decorate handles and facets of the bowl’s flap cover. Its knob is made in the shape of a double-headed eagle.

The jug above is made of silver and stylised as a clay vessel – a traditional milk pot with a spherical, slightly flattened belly, a stemmed, cylindrical base, a tall wide neck, and a vertical scroll handle.

There is a piece of text written along the central part of the ewer and stylised as Vyaz’: “OUR ANCESTORS ATE SIMPLE FOOD AND LIVED FOR ONE HUNDRED YEARS.”

Rich, beautifully combined colours were the distinctive feature of items produced by Khlebnikov’s firm. Flowers with soft pink petals on a bright turquoise background with large, green, swirling offshoots decorate all four panels of this casket. The enamelled pattern that adorns the casket’s cover and panels is supplemented with smooth convex cabochons (shaped and polished gemstones).

The Workshop of F. Rückert and the Rise of Russian Enamel

The workshop (later it grew into a factory) of Fyodor (Friedrich) Rückert (1851-1918) was one of the best firms in Moscow that worked with enamel at the turn of the 20th century. Rückert was one of the first manufacturers to use enamels with multicoloured spots (“splashes”) and to decorate his products with amalgam and “knots” made in the skan’-and-enamel technique.

The workshop produced small and big dippers in great numbers. They were inspired by peasant ladles, dippers for pouring liquids from Veliky Ustyug and Vologda, and dippers in the Kozmodemyansk style with their tall handles decorated with geometric openwork.

Quite often products were adorned with miniature enamelled paintings on matte surface. They copied pieces of famous artists of that time (V. Vasnetsov, K. Makovsky, S. Solomko, et cetera). These paintings became known as en plein. For example, this jewellery box is decorated with an oval panel that reproduces the painting of Konstantin Makovsky “Working at a Tambour Frame” (1888).

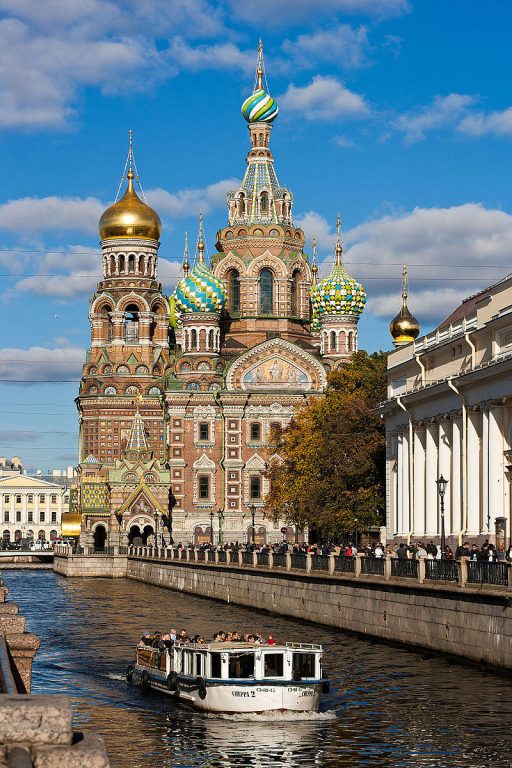

An enamelled miniature made in the en plein technique decorates the back of this spoon. It reproduces the painting of A. Beggrow “A View of Petersburg from the Neva.” The miniature is framed with floral and geometric patterns with circles, triangles, waves, and leaves. The colour scheme here is based on blue, green and grey shades and tones.

We worked on this article about the “Russian style” in enamels of the 19th – 20th cc. in cooperation with the Museum “Collection.” You can find some of the Museum’s objects in the archive of Ornamika. We would like to thank Yulia Lisenkova for helping us prepare this material and describe ornaments of enamels from the Museum’s collection.

Works cited:

- Bitsadze N. V. Churches in the Neo-Russian Style (in Russian). Ideas. Problems. Customers. Moscow, 2009

- Kirichenko E. I. The Search for the National Identity and Its Manifestations (in Russian). Nation and Nationality. Moscow, 1997

- Kovarskaya S. Ya. Products of Klebnikov’s Firm from Moscow (in Russian). Moscow, 2001

- Muntyan T. N. Fyodor Rückert & Carl Fabergé (in Russian). Moscow, 2016.

- Oser J. Talashkino. Wooden Articles Made by the Workshop of Princess Maria Tenisheva (in Russian). Moscow, 2016

- Savelyev Yu. R. The New Concept of Tsarism and the “Russian Style” (in Russian) // Vestnik of Saint Petersburg University. History. №. 4, 2006

- Smorodinova G. G. Products of Ovchinnikov’s Firm in the Collection of the Historical Museum (in Russian). Moscow, 2016

- Salmond Wendy R. Arts and Crafts in Late Imperial Russia: Reviving the Kustar Art Industries, 1870-1917. Cambridge, Melbourne, and New York: Cambridge University Press, 1996

Editors of this article: Elizaveta Berezina, Madina Kalashnikova.