The Cosmos, Time, and Ornaments

Since ancient times, people have been watching the motion of celestial objects. They tried to understand the way the world works and to comprehend the flow of time. Astronomical observations helped people to create first calendars and formed the basis for astral and cosmogonic myths that explained the origins of the world, people, and natural phenomena. However, on April 12, 1961 dreams about outer space came true. To celebrate the anniversary of the first human space flight, we collected patterns with solar, lunar, and stellar motifs.

Source: The Antiquarian. Journal of Art and Collecting [in Russian]. 2013. № 77, October.

The Sun and the Moon

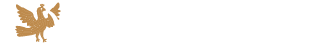

The Sun on a Dish

The surface of this dish from village Ispik in Dagestan is covered with dense painting. Its constitutive elements are round rosettes (solar symbols), flamboyant swirls of floral ornaments, and triangle patterns that decorate plate’s borders. Empty space is filled with dots that unite different parts of the composition into a single whole. Such dishes were not used in everyday life, but had a decorative function. Two holes for hanging an item on a wall were made in a plate’s bottom even before baking.

The Late Transformation of Solar Symbols

Click on the image to see the item’s profile

This well-preserved fragment of headwear comes from the Kostroma Governorate. A circle comprised of rhombi with a solar sign inside forms the upper part of its ornamental composition. Below the circle, there is a female figure flanked by birds. Another solar symbol in the upper part of the pattern is also flanked by two figures of birds sitting on tree branches. Their heads are turned back. In the lower part of the composition there are small birds and floral ornaments.

The Sun in Architecture

Click on the image to see the item’s profile

In architecture, symbolic manifestations of the Sun is a rather common element. The Big Bridge over the Ravine from the Tsaritsyno Palace Ensemble can serve as an example. Vasily Bazhenov who architected this bridge decorated the central part of its façades with rosettes in a form of small suns. By Bazhenov’s design, the façades resemble fronts of Gothic cathedrals with a large central portal and smaller side portals. Ornamental elements above them refer to Gothic rose windows. In the decoration of this bridge and other buildings in Tsaritsyno, Bazhenov also used other similar forms, such as crossed rhombi, zigzags, circles and squares. The architect borrowed these elements from traditional folk ornaments, yet he creatively re-interpreted them to make new compositions. In Russia, such motifs can be found in carved decorations of peasant dwellings, in embroidery on folk dresses, shirts and tablecloths, or in paintings on household utensils.

Click on the image to see the item’s profile

Ancient ornaments also inspired Sergey Malyutin, an artist who designed adornments for the revenue house of Zinaida Pertsova in Moscow. The maiolica decoration includes images of mythological creatures, the Sun and flowers, animals and fish. This sophisticated design reflects the individual style of Malyutin that is characterised by “colourful elements: cornices, bas-reliefs, swirls of monstrous flowers and strange swans with fanned tails, lubok-like suns, waving threads of various circles, stripes, stars, and squares.” Malyutin decorated one of the windows with a sun and radiating rays. Triangles with rounded angles that are placed between the rays create the imagery of the vibrating flow of sunshine.

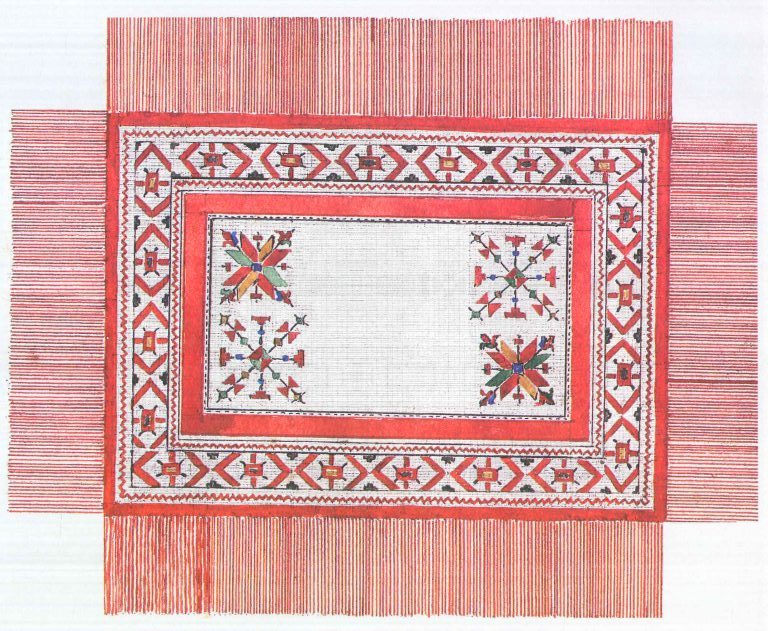

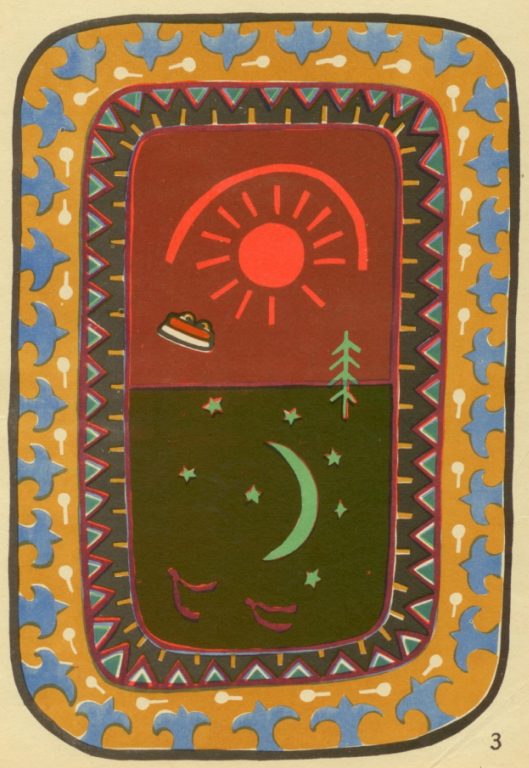

A Lunar Pattern Toleźo

Click on the image to see the item’s profile

In traditional ornaments, lunar patterns are not as common as solar signs. Yet, for Udmurt folk embroidery, ornaments inspired by the Moon, such as an eight-pointed star “toleźo,” are one of the most important motifs. For example, the “toleźo” pattern decorates festive aprons that were an integral part of wedding costume. A bride would put it on when she moved to the bridegroom’s house and changed her maiden clothes to woman dress. The wedding ornament “toleźo” reflects the cult of fertility and the concept of procreation. The pattern consists of four parts, each standing for a particular stage of human life: birth, maturity, ageing, and death. In the mythological image of the world, these stages are connected to lunar phases.

Click on the image to see the item’s profile

The composition of this Altai felt rug might bring to mind colourful appliqués that children usually make. The goundwork of the carpet is divided into two parts. A red sun decorates the centre of the upper part, while a green moon and stars adorn the lower one. In a simple, folk manner this carpet reflects beliefs of an ordinary person, their understanding of day and night cycles, and the idea of eternal recurrence.

Stars

A Firemane Lion and a Bright Start

Click on the image to see the item’s profile

This round golden plate could be used for the decoration of clothes or headgear. The item is adorned with the image of lion and two seven-pointed stars. This ornamentation is both laconic and expressive, its composition is rather simple, while the drawing is quite accurate.

A Rare Icon Made of Nacre

The basis of the composition is an eight-pointed star covered with light beige velvet. Embossed palm branches surround square nacre plates on diagonal grids. Each plate is supplemented with a multi-figured low relief composition on Evangelic motifs, figures of saints and martyrs, and a description. Apart from these elements, there are four cherubim placed in four tips of the star, each accompanied by two angels. The edging of the figure is decorated with small stars also made of mother-of-pearl.

Chuvash Köskö-Stars

The chest embroidery on female shirts (köskö) exemplifies the beauty of Chuvash ornaments. Combined together, patterns comprise an eight-pointed pattern with an octagon or a square in its centre. Some researchers tie the eight-pointed shape of köskö with its radiating spoke-like lines to the imagery of stars or the Sun that embody a source of life.

The Universe and the Cosmos

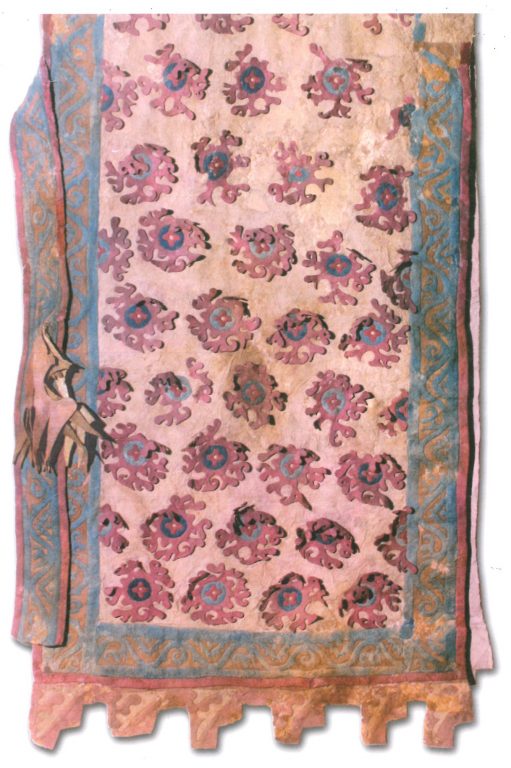

The Cosmos in the Perception of Ancient Peoples of the Altai

Click on the image to see the item’s profile

The Pazyryk shabraque (a saddle blanket) is made of thin white felt and is decorated with ornamentation. Each figure here is a complex element that symbolises the sky and the Sun. They are comprised of a blue circle with a four-pointed red rosette sewn to its centre with white threads. The pattern is framed by five figures in a shape of stylised deer horns made of thin pink felt. Their edgings are not attached to the background, so the horns flutter from the slightest touch, this way making the overall composition more dynamic. The borders of the shabraque are adorned with schematised images of a griffin’s head, lotus flowers, and rippled lines that have small “offshoots” (deer horns). Such ornamentation could reflect beliefs of early nomads about the Universe and the Cosmos, and might be tied to their worldview system.

A Year Cycle in the Decoration of an Ancient Dish

The motif of seasons have attracted significant attention on the part of artists and artisans from different regions. In the 17th and 18th centuries, the subject became especially popular in wood painting, as can be seen on the example of this dish. In the centre of the plate, there are four figures each sitting on a throne. They personify four seasons: spring, summer, autumn, and winter. Various items the figures hold in their hands, as well as their clothes and surrounding landscapes indicate their roles. In the very centre of the dish, there is an image of a lion and a unicorn having a fight. The rest of the surface is covered with floral patterns that depict offshoots growing from jug-like figures. The overall composition shows the complex system of the world order and the attitude of humans toward nature.

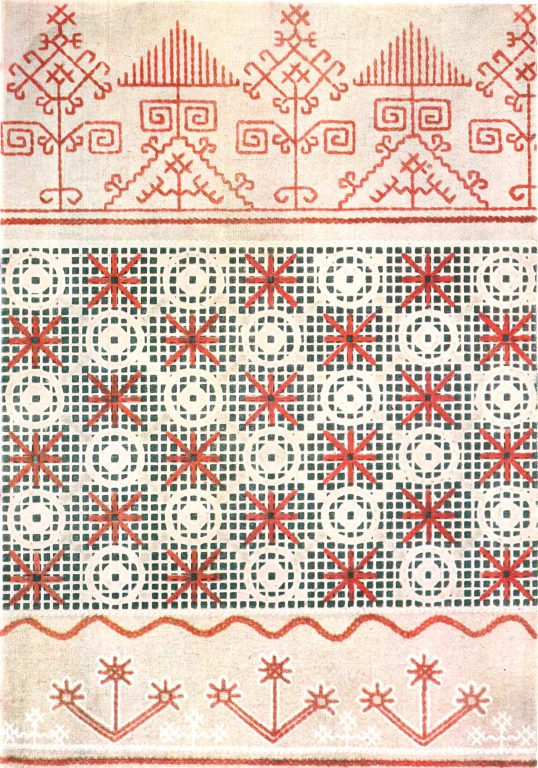

A Sown Field or the Firmament?

Folk embroidery frequently reflects the way people understand the world. This edging from Arkhangelsk has small elements embroidered chequerwise that evenly cover the whole surface of the article. Its three-part composition may have different explanations. Its central part can be interpreted as both a sown field (a symbol of fertility) and as the firmament with stars. Such patterns symbolise harmony in the Universe, which is transferred to the everyday life of people through houseware.

The Universe in Tablecloth Ornamentation

Click on the image to see the item’s profile

Large rosettes that symbolise the Sun, stars that cover the blue surface of the fabric, silhouettes of birds, joined rings, and many other elements in the ornamentation of this woodblock printed tablecloth represent ancient cosmogonic and cult beliefs. People have covered festive tables with an ornamented cloth since ancient times, but in some villages, there was a practice of covering graves with tablecloth. The ritual took place during special celebrations when people came to cemetery to commemorate their deceased relatives. This practice can stem from ancient pagan and Christian beliefs, where “a tablecloth turned into a festive covering of a throne” or an altar. Perhaps the ancient meaning of the ornamentation was lost, and people who produced such tablecloths did not know all the details, but they still followed the old tradition.

Works cited:

- Barkova L. L., Polosmyak N. V. The Costume and Textile of the Pazyryks from the Altai (4th – 3 th cc. BC) [in Russian]. Novosibirsk: Infolio, 2005.

- Ancient Novgorod: Applied Arts and Archaeology [Photo album]. Ed. by Yanin V. L., Kolchin B. A., Yamshchikov S. V. Moscow: Iskusstvo, 1985.

- Durasova G. P., Yakovleva G. A. Pictorial Motifs in Russian Folk Embroidery [in Russian]. Moscow: Sovetskaya Rossiya, 1990.

- Kashkarova Z. D., Rabotnova I. P. Folk Embroidery from Arkhangelsk [in Russian]. Moscow: KOIZ, 1954.

- Ceramic Installation: From the Materials of the Archive and Collections of A. V. Filippov [in Russian] / [research ed.: S. I. Baranova]. Moscow: Eksmo, 2017.

- Medzhitova E. D., Trofimov A. A. Chuvash Folk Arts [in Russian]. Cheboksary: Chuvashskoye Knizhnoye Izdatelstvo, 1981.

- Folk Arts. Research Materials [in Russian]. Vol. 2. Collection of articles. Saint Petersburg: Palace Editions, 2005.

- Chirkov D. A. Decorative Arts of Dagestan [in Russian]. Moscow: Sovetskiy Khudozhnik, 1971.

- Edokov V. I. Altai Ornaments [in Russian]. Gorno-Altaisk: Knizhnoye Izdatelstvo, 1971.

- Experts from the National Museum of the Udmurt Republic named after Kuzebay Gerd.

- Experts from the Tsaritsyno State Museum Reserve.

Editor of this article: Elizaveta Berezina.