The Unique Archaeology of the Ust’-Poluy Sanctuary

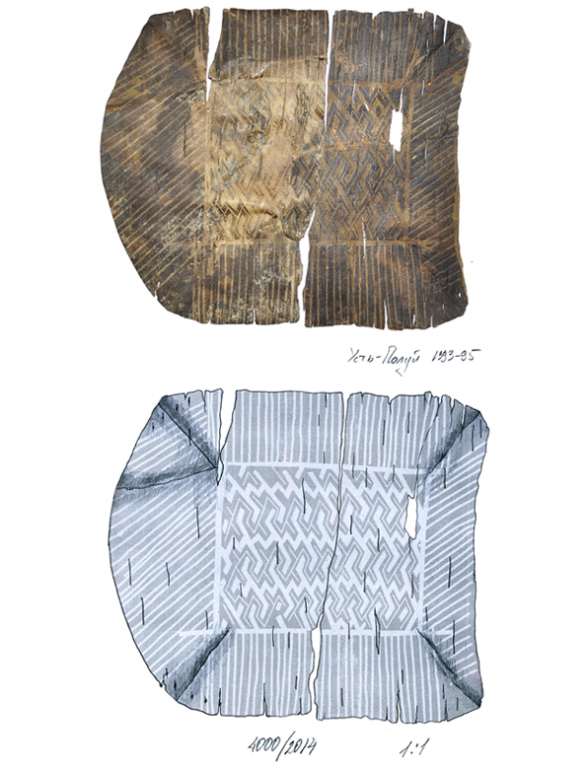

Have a look at this subtle and accurate pattern, feel its rhythm. This ornament is more than 2000 years old.

The ornamentation on the surface of this birch bark box has survived due to the natural conditions of the Extreme North, efforts of archaeologists, and diligent work of restorers.

Citizens of Salekhard, a town situated on the shore of the river Poluy near the Ob, have frequently found unusual objects, such as tiny figures made of bone and metal, arrowheads, or knife handles. Right underfoot, close to a road, garages, and other outbuildings, there is a unique archaeological site of the Iron age – the sacrosanct and manufactural centre of Ust’-Poluy (II c. BC – II c. AD).

First excavations carried in 1935-1936 by Vasily Adrianov (1904-1936), a young archeologist from Leningrad, were a true revelation. The findings included well-preserved objects made of bronze, stone, horn, bone, and ceramics. There were also some fragments of birch bark, but they were of no interest for the researches at that time.

However, when 75 years after that the team of archeologists under the guidance of Andrey Gusev started excavating a moat around the sanctuary, they found more than a hundred bark boxes. Some of them were decorated with fine and complex ornamentation.

Veronika Mogritskaya who was involved in excavations comments on the findings:

The Birch Bark Boxes from Ust’-Poluy and Their Ornamentation

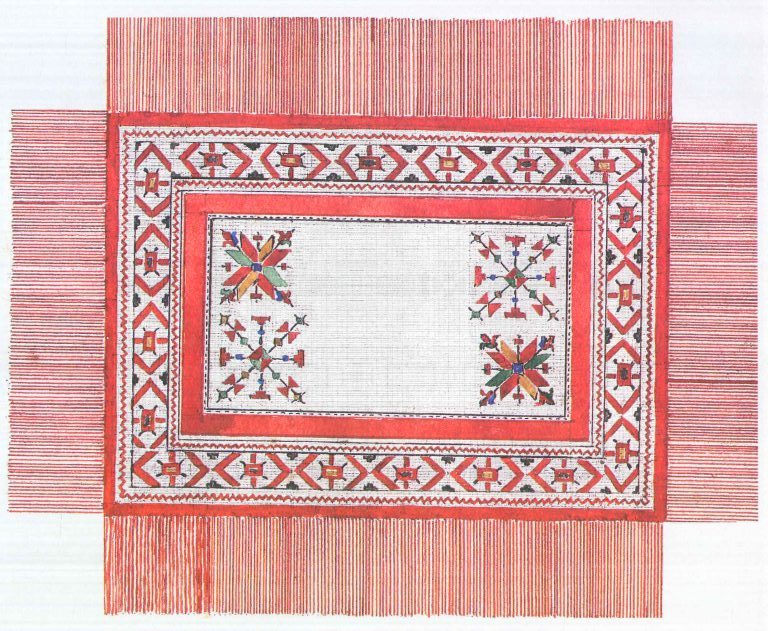

Just like the historic site itself, the ornamentation of the birch bark boxes dates back to the II c. BC – II c. AD. The quality of work is amazing: artisans who created these boxes centuries ago worked accurately and rigorously, making fine straight lines and inclining all the elements of the pattern at equal angles. The overall composition was made with delicacy and precision: some lines and elements are only 2-3 mm thick. However, some later findings show incomplete and rough lines and inaccurate patterns – this fact designates the subsequent degradation of the craft.

An archaeological object

The sacrosanct and manufactural centre of Ust’-Poluy

To produce these ornaments, artisans scraped the dark layer on the inner side of bark with a sharp tool. Scraping the material, a craftsman could not avoid pressing it, which resulted in the pattern being slightly convex. Nowadays the same technique is used to decorate items made of birch bark.

An archaeological object

The sacrosanct and manufactural centre of Ust’-Poluy

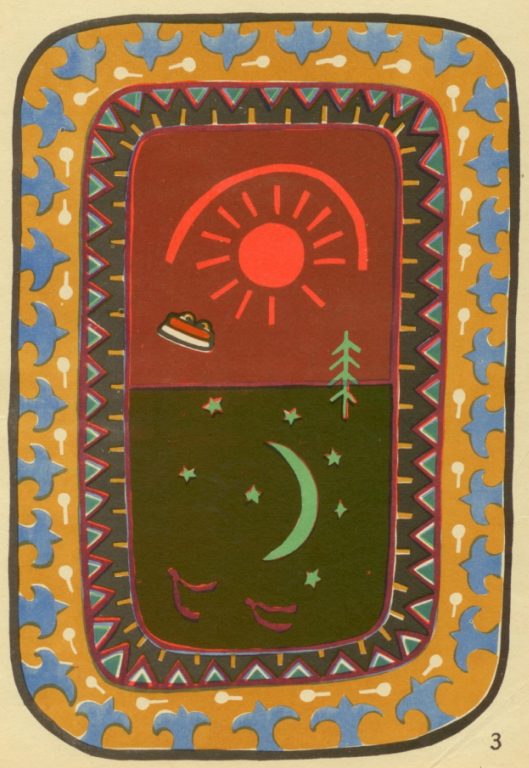

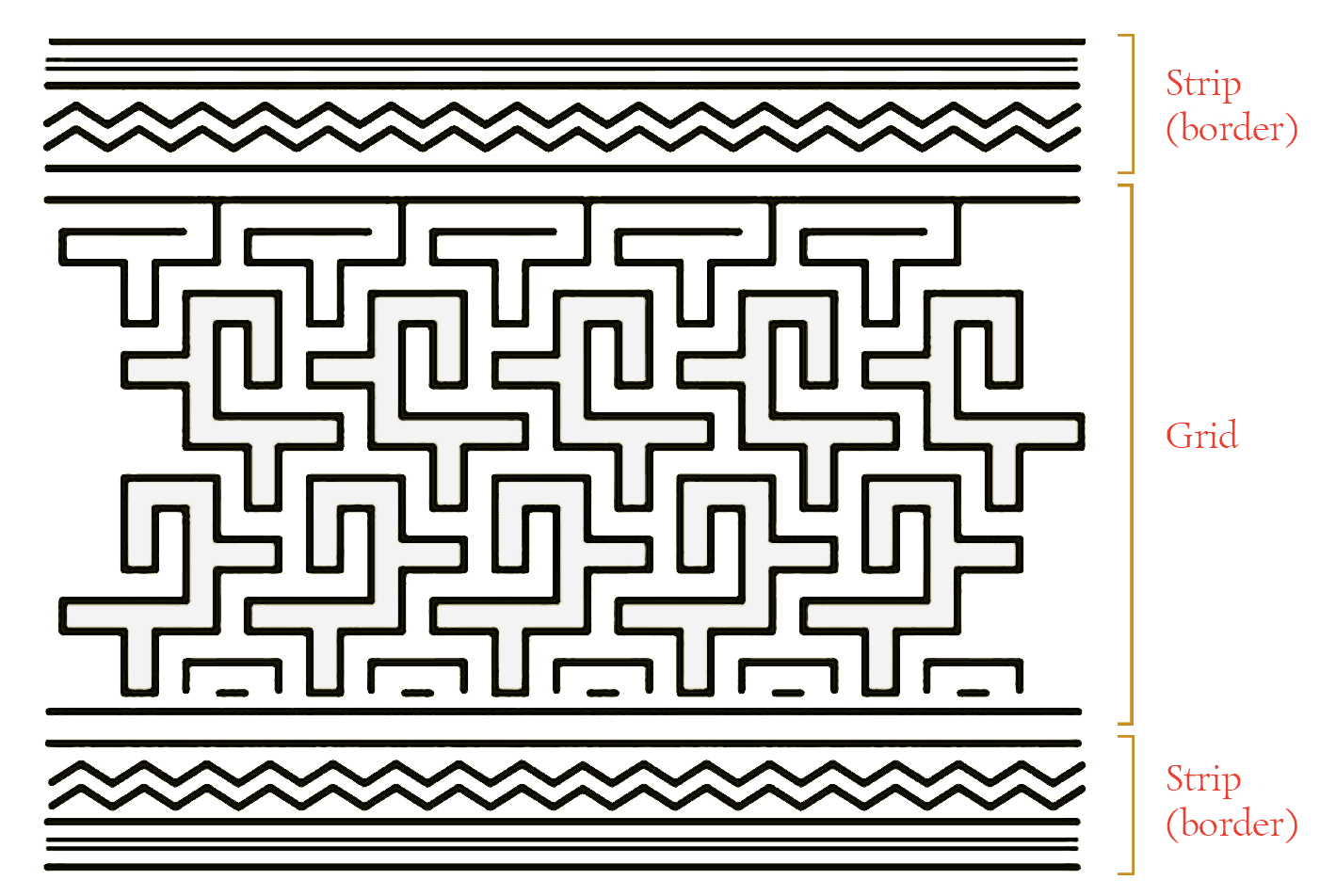

There are two major motifs characteristic for the decoration of Ust’-Poluy boxes – these are strips and grids (see the picture below). Both resemble geometric patterns; their variations are based on the angle inclination of lines. One of the most typical decorative elements is a meander – the pattern constructed from continuous lines positioned at a right angle.

The ornamentation consists of enclosed and open compositions. Some boxes found also contain complex enclosed patterns with images of birds or animals placed in their centre. For some ornaments, a swastika served as a constitutive element.

An archaeological object

The sacrosanct and manufactural centre of Ust’-Poluy

The shape of these boxes is quite unusual: their sides are finely curved and widen towards the mouth. Artisans from Ust’-Poluy could make a whole box using only one piece of birch bark. Sometimes they sewed together two layers of bark to produce a more solid item.

Some boxes have a cylindrical shape. They have a round bottom, and their sides are made of a bark strip. The diameter of such containers and their height can vary, but the precision of their design and the accuracy of stiches remain unsurpassed even today.

An archaeological object

The sacrosanct and manufactural centre of Ust’-Poluy

Special Properties of Birch Bark and the Conditions for Its Preservation

The observation of teared fragments of birch bark allow assuming that some boxes were purposely damaged. Undamaged boxes found by archaeologists contained animal bones, fur and textile pieces; one box even contained a mummified bird’s carcass. Researchers think that all these items could be used for rituals and rites of sacrifice.

The sacrosanct property of these boxes is designated by the material used for their production. Many peoples of the North see the birch as a sacred tree; they believe that its bark has protective and cleaning functions. Birch bark was used to make baby cradles, to cover deceased before burials, to produce ritual tableware and hygienic tools.

Now we know that some agents found in birch bark have antiseptic properties. Ancient people probably noticed that food placed in the tableware made of birch bark stays fresh for a long time; they might have also learnt that tar helps cure injuries. This explains why they started using items made of birch bark for both everyday tasks and ritual practices that demanded special hygienic conditions.

Soft organic materials are rarely found during archaeological excavations: fur, fabric, and wood easily decompose in soil. However, the Ust’-Poluy sanctuary is located in the Permafrost area, where only the upper 40-100 cm of soil thaws even in warm months. Even if digging on a hot summer day, one would soon reach a layer of ice. Water concentrated in soil in this area remains frozen all the time, which creates perfect airless conditions for the preservation of organic materials.

Who Were the Ust’-Poluy People?

The settlers of Lower Priobye (one of the regions close to the Ob river) were not primitive savages, although some old ethnographic sources describe them this way. The archaeological findings from the sacrosanct and manufactural centre of Ust’-Poluy prove that its ancient visitors were people with high-developed crafts, beliefs, and the peculiar knowledge transfer system.

However, the Ust’-Poluy people did not have any writing system – that is why archaeological artefacts serve as the main source of information about their life. For example, arrowheads found in the area prove that the Ust’-Poluy people used bows, and tools for bronze moulding allow suggesting that they were proficient in working with metal.

The investigation of the Ust’-Poluy historic site has raised many questions: what was the exact purpose of this place? For which rituals was it used? What was its role in the everyday life of settlers of the Extreme North? Researches still hope to learn more about the culture and beliefs of those who visited the Ust’-Poluy sanctuary.

An archaeological object

The sacrosanct and manufactural centre of Ust’-Poluy

Ornaments can tall a lot about those who created them. For instance, the comparison of patterns used in the decoration of Ust’-Poluy boxes with the ornaments of other ancient cultures helps find connections between different peoples and track their resettlement across Eurasia. Researchers concluded that the ornamentation of Ust’-Poluy boxes is akin to patterns used in the Andronovo culture – the more ancient and southern one. Nevertheless, there is still no exact answer on how the distinctive culture of the Ust’-Poluy people emerged and developed.

(The illustration from: The Archaeology of the Arctic. Vol. 4. “Ust’-Poluy: The Materials and Examinations”: monography in 2 parts, part 2. Edited by O. N. Korochkova – Ekaterinburg. Delovaya Pressa Publishing House, 2017. P. 223)

Among modern peoples, the Nenets probably have the closest connection to the Ust’-Poluy people. There is a tale in the Nenets folklore about a mythical underground folk called sikhirtya (sirtya) that lived in the Arctic area before the Nenets. Sikhirtya are described as stocky people who were talented metal workers, keepers of silver and gold. Perhaps this image of sikhirtya was influenced by the early contacts of the Nenets with the autochthonous inhabitants of this region, who could have been the Ust’-Poluy people. Inter-ethnic marriages and continuous presence of different tribes on the same territory led to the dissolution of the Ust’-Poluy people and their culture among other peoples, such as the Nenets, the Khanty, and the Mansi.

We would like to thank Veronika Mogritskaya, Senior Researcher of the Department of Archaeology of the Shemanovsky Museum-Exhibition Complex, for helping us to write and illustrate this article..