THE CHUVASH

The Chuvash people (endomyn: чăваш (çăvaş); Russian: chuvashy) are a Turkic ethnic group, the fifth largest ethnic group in Russia. According to the 2010 census, there are 1 435 000 Chuvashes in the country; more than half of them reside in the Chuvash Republic (Chuvashia). Although Chuvashes may be found in almost all regions of Russia, the majority of them lives in the Volga Region. Researchers distinguish three main groups of Chuvashes depending on where they live in relation to the Volga: the Upper Chuvash (also known as Virjal or Turi) who live in the west and northwest of Chuvashia, the Lover Chuvash (Anatri) from the southern territories and surrounding areas of the Republic, and the Mid-Lower Chuvash (Anat Jenchi). These groups used to vary in their modes of life and material culture in the past, but now these differences have become less marked.

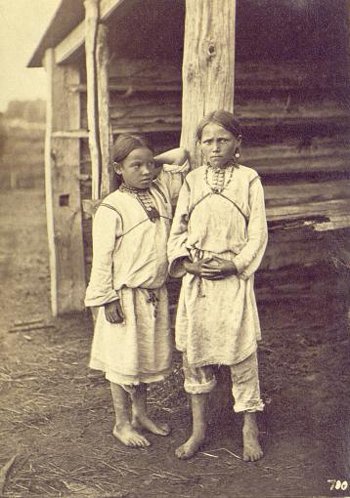

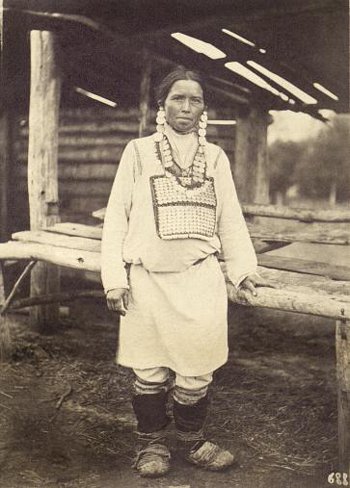

This article focuses on a specific topic – the Chuvash wedding ornaments. Let us start by looking at some photos from the real Chuvash weddings of the late 19th – early 20th centuries (any older materials could not be found).

FROM A MEETING TO A WEDDING

Young men and girls from different villages usually got acquainted with each other during various celebrations and games. Apart from that, a prospective spouse could also be met on a nima – an event when several families gathered to perform laborious tasks such as harvesting or forest transportation. After young people got to know each other and the matchmaking was over, the families started wedding preparations.

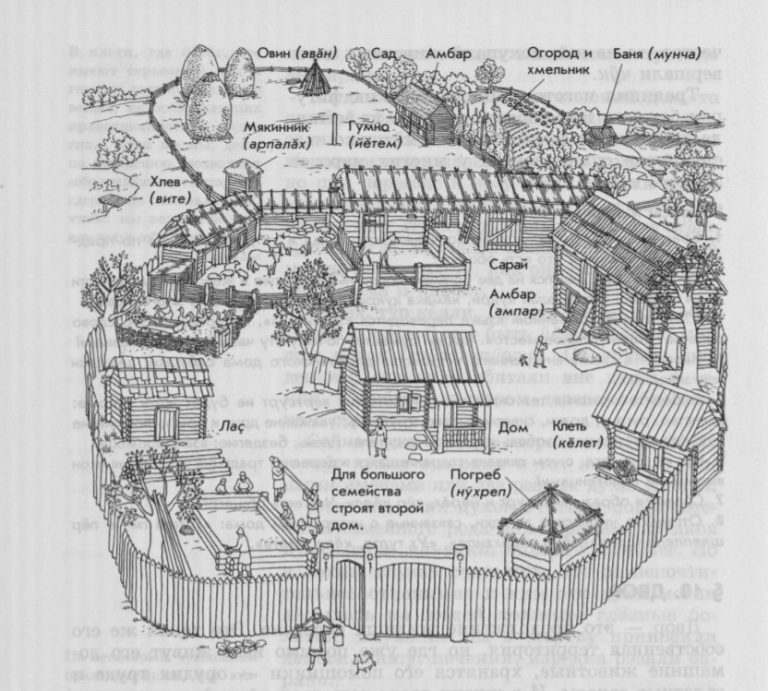

Newlyweds got their own house, which was placed close to the home of bridegroom’s parents. The dwelling was built in the centre of a yard surrounded by various outbuildings. This way Chuvash villages used to grow and develop until the 1870s, when new regulations prescribed to construct straight, linear streets and orient the buildings’ facades to them.

A traditional Chuvash wedding would last for several days. It was a big celebration for both villages (as usually future spouses were from different villages) with many people involved from both the groom’s and the bride’s sides. The roles of guests were predefined and clear to everyone. The most important people were the head of the wedding procession, the senior groomsman (druzhka; usually a brother or a best friend of a groom who helped regulate the procession), the junior groomsman, the carrier of the wedding bag, bridesmaids, musicians, hăjmatlăh (a married couple selected to perform different rituals), văj(ă) puşö (an unmarried relative of a bride), et cetera.

People in senior positions controlled the actions and behaviour of others and were in charge of wedding rites. However, not only rituals were used to protect newlyweds from evil and guarantee the prosperity of their partnership. Household items and the items of clothing also had various symbolic meanings, apart from their practical functions. Wedding costumes were richly decorated with ornaments that symbolised procreation and were believed to protect those who wore them.

THE BRIDE’S COSTUME

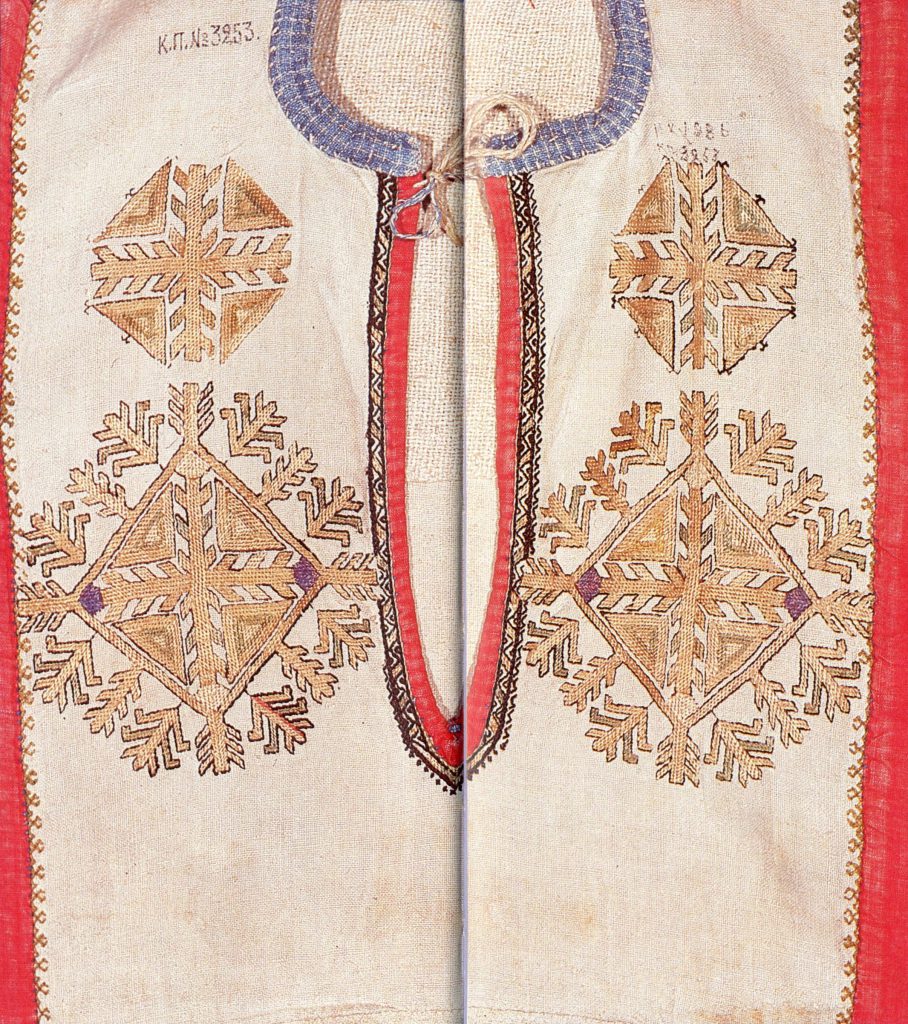

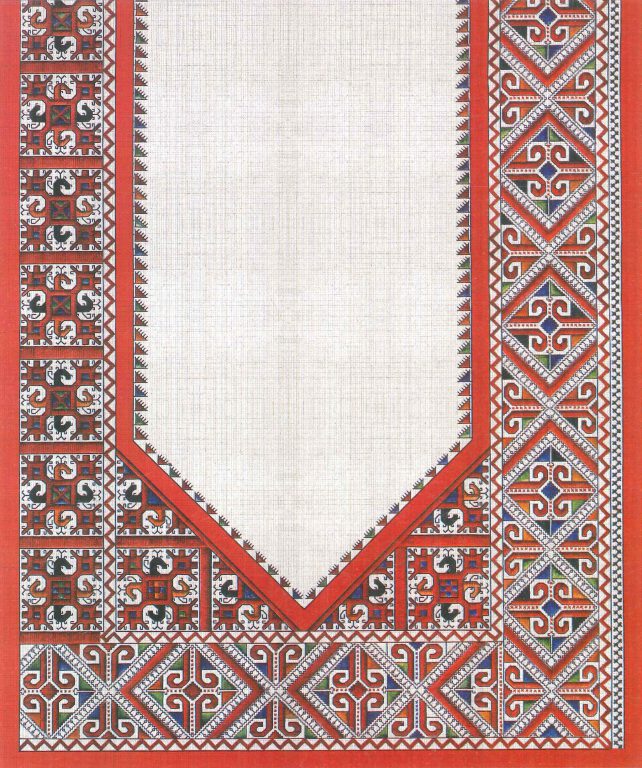

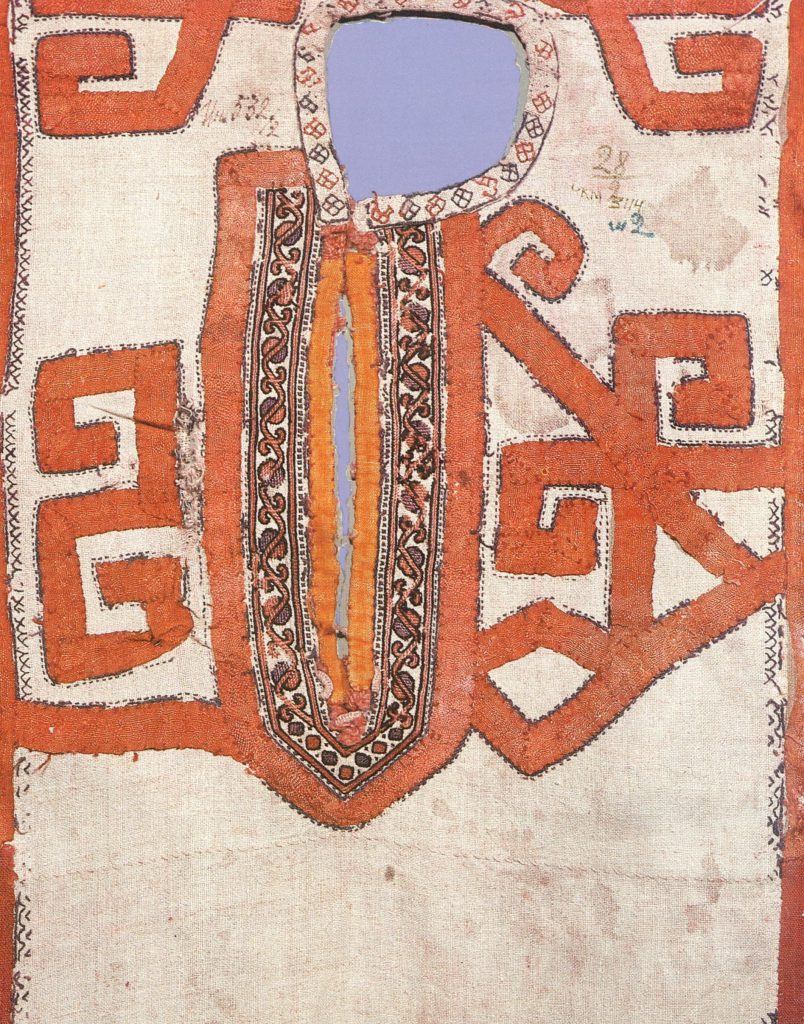

A Chuvash bride should have dressed in a non-residential part of a house, usually in a lumber room or in a granary. Bridesmaids helped the girl to put all the items on; a groom’s sister or the so-called proxy parents (those who were not the real parents of newlyweds, but who were chosen to perform some significant functions) had the upper hand. The bride dressed in new fresh clothes – a white burlap shirt decorated with embroidery, and an apron. She wore her best accessories and put on a caftan made of black or blue thin fabric with a lining (pustav, jölen) or a white robe with rich embroidery (šupăr).

The chest embroidery was what distinguished a shirt of an unmarried woman from that of a married female. The ornaments on maiden shirts usually had asymmetrical compositions of skewed lines and rhombi decorated with embroidery (suntăh). The chest slit was positioned on the right side of a shirt. According to Igor Petrov, a researcher of the history, ethnography, and folk art of Chuvashes from the Ural-Volga Region, the asymmetrical composition signified that the owner of a shirt was not married but had reached puberty.

In contrast to unmarried women, married females wore shirts with two, four, or more symmetrical patterns made in the shape of eight-angled stars and placed on the both sides of the chest slit. On the first day of the wedding, the bride would wear the maiden attire, and only after the first wedding night she could change it to the apparel of a married woman.

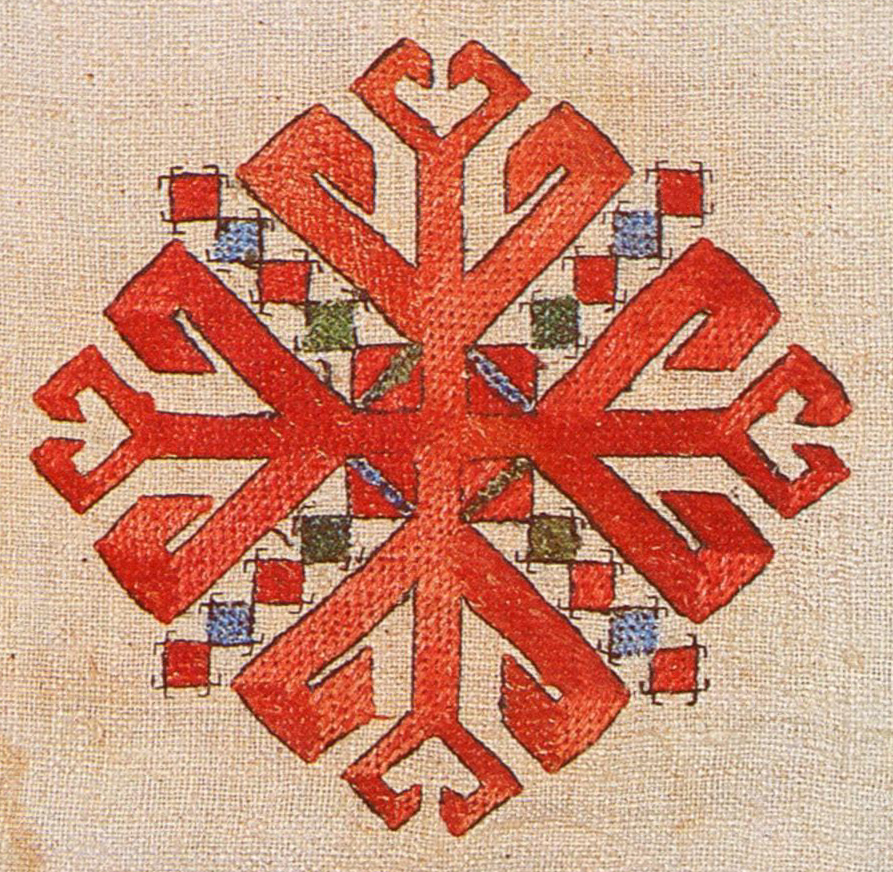

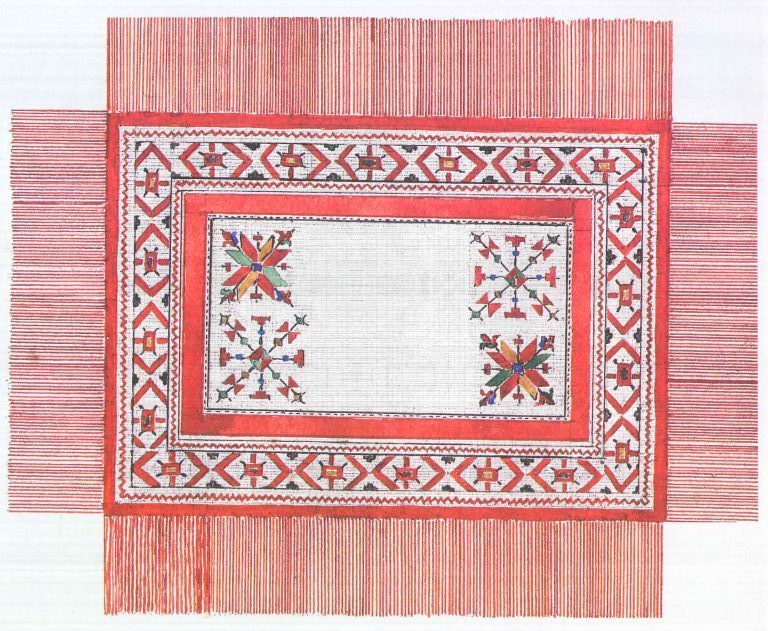

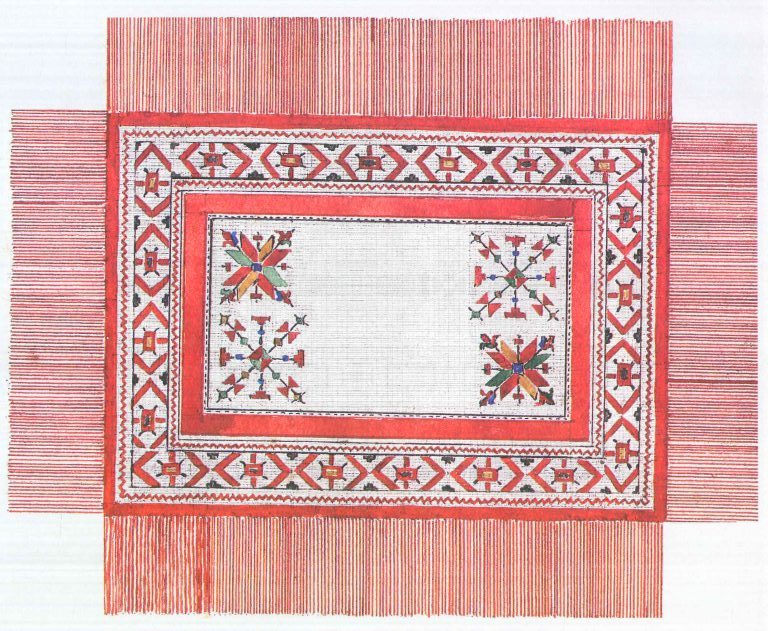

A pörkençök, a wedding scarf, is another important article of the Chuvash bridal costume. It is a large rectangular piece of fabric (approximately 150 x 120 cm) made of several strips of white thin canvas stitched together. The pörkençök veiled the bride’s face and covered her body. The edges of the scarf were decorated with silk or cotton ribbons and sophisticated ornaments in the form of eight-angled stars placed on the both sides of the article.

The pörkençök covered a maiden hat (tuhja). According to the tradition, the bride had to refuse to put on the scarf: she stripped it off three times, and only after that she veiled her face. After this ritual, the girl went to an izba to lament – this action symbolised her transition to the other world (the family of her groom) and the parting with her family. The pörkençök was put off only when the bride entered the house of groom’s parents, and when the newlyweds tasted a special soup. This ritual is called the maiden salma. Vasily Sboev (1810-1855), a writer and an ethnographer who created the first monograph about the Chuvash people, described the ritual with the following words:

‘The closest relative of the bridegroom takes a tree branch and, encouraged by clapping and screaming guests, dances and hops to the music, moving from a threshold to benches, squatting and standing up again. When he approaches the bride, he touches her veil with the branch; he does it again, and then, for the third time, he finally takes it off with his branch. Holding the scarf, he leaves the izba for a while.’

This man, the druzhka, hid the pörkençök in a klet’ (the non-residential part of the house connected to the izba via an entryway). The scarf was protecting the bride while she moved from her parents’ dwelling to the house of her parents-in-law. The ornamentation of the pörkençök symbolised the power of her ancestors and the family she left, and protected her during her transition to the new family. After the rite was over, the bride took off the maiden hat (tuhja) and put on a surpan or a hušpa (the headwear of married women).

THE KÖSKÖ ORNAMENT

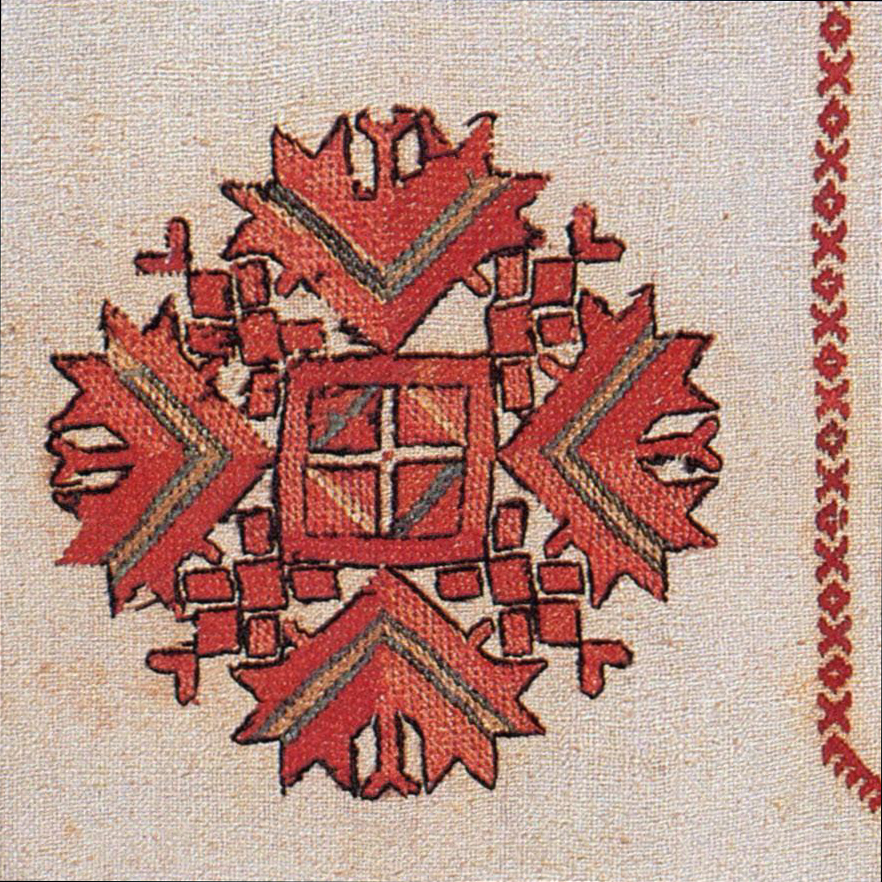

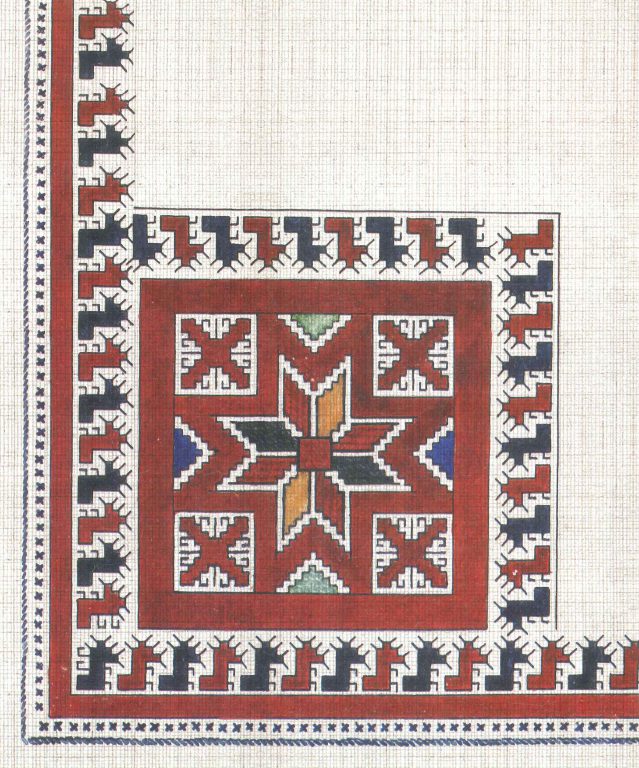

The chest embroidery of female shirts (köskö) exemplifies the beauty of Chuvash ornaments. It was made with intricate stitches, with silk or woollen threads. The motifs of köskö embroidery are very rich: they include geometric, animal, and floral ornaments. Combined together, they comprise an eight-angled pattern with an octagon or a square in its centre. Some researchers tie these eight-angled figures with spoke-like lines spreading from their centre to the image of the Sun as a source of life. In its early versions, the pattern could have a round-shaped composition: the Sun represented by a circle with spreading rays is a common motif in crafts of many nations.

The eight-angled köskö stars might be understood as:

a) the Sun;

b) the flourishing World Tree;

c) the ornament that guarantees a well-being of the owner and emphasises her connection to her ancestors;

d) the ornament that represents the Chuvash conception of the world, the universe;

e) the ornament that has a purely decorative function.

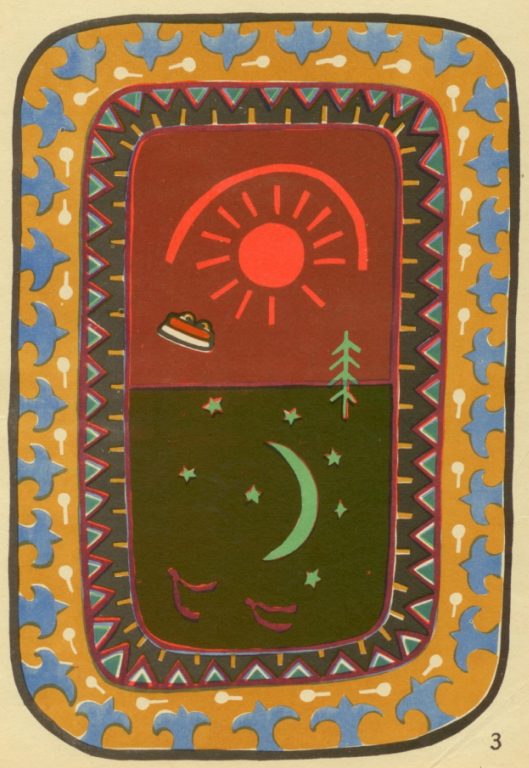

Researchers argue that the köskö pattern reflects the ancient image of the world. According to the old beliefs of Chuvashes, the universe has a square-like form with 4 or 8 angles (two squares put one on another) and consists of three subworlds (layers):

1. The Upper world. It has three or seven levels inhabited by gods and benign spirits. Celestial bodies (the Sun, the Moon, and stars) also live there.

2. The Bright world. This is where people and animals live. It has a world mountain (ama tu) in its centre with a world tree (ama jyvad) growing on it. The tree’s crown grows up to the Upper world, while the roots go down to the Lower world. Tree’s branches reach all the angles of the world, thereby supporting the firmament.

3. The Lower world. It has three or seven levels inhabited by evil spirits and monsters; it is seen as the remaining of chaos.

Later the Upper world was connected to the concept of Paradise (datmah, adtamah), and the Lower world was compared to Hell (tamak). All these beliefs are reflected in Chuvash folk songs, such as this one:

…Oh, the eight-angled Universe,

There are eighty eight seas in this eight-angled Universe,

And there is a golden island in the centre of these eighty eight seas.

There is a golden mountain on the golden island,

There is a golden fence on the golden mountain,

The golden fence surrounds the oak tree,

And this oak tree has seven roots.

The seven roots reach the underworld.

The trunk of this oak tree is golden.

The golden trunk stretches towards the seventh sky.

This oak tree has eight branches,

The eight branches reach the eight angles.

THE BRIDEGROOM’S COSTUME

The bridegroom’s wedding garment was the type of male holiday costume. Like in the bridal clothing, in the groom’s attire there were many elements that had a protective function. A groom should also have dressed in a non-residential room – in a klet’ used for storing grains. He put on a new fresh shirt, and woollen or broadcloth sharovary (a type of pants). Usually the wife of his elder brother or other relative, or the wife of a senior groomsman, or the wife of the bride’s elder brother helped the groom to get dressed. Sometimes the bridegroom’s shirt was decorated with an elegant detail – a white delicate perevit’ (a type of an openwork embroidery). Male wedding shirts were long, wide, with straight sleeves and a chest slit on the right side, a red gusset, and richly decorated bottom edges. A caftan or a robe girded with kushak (a type of a waistband) served as an outer garment.

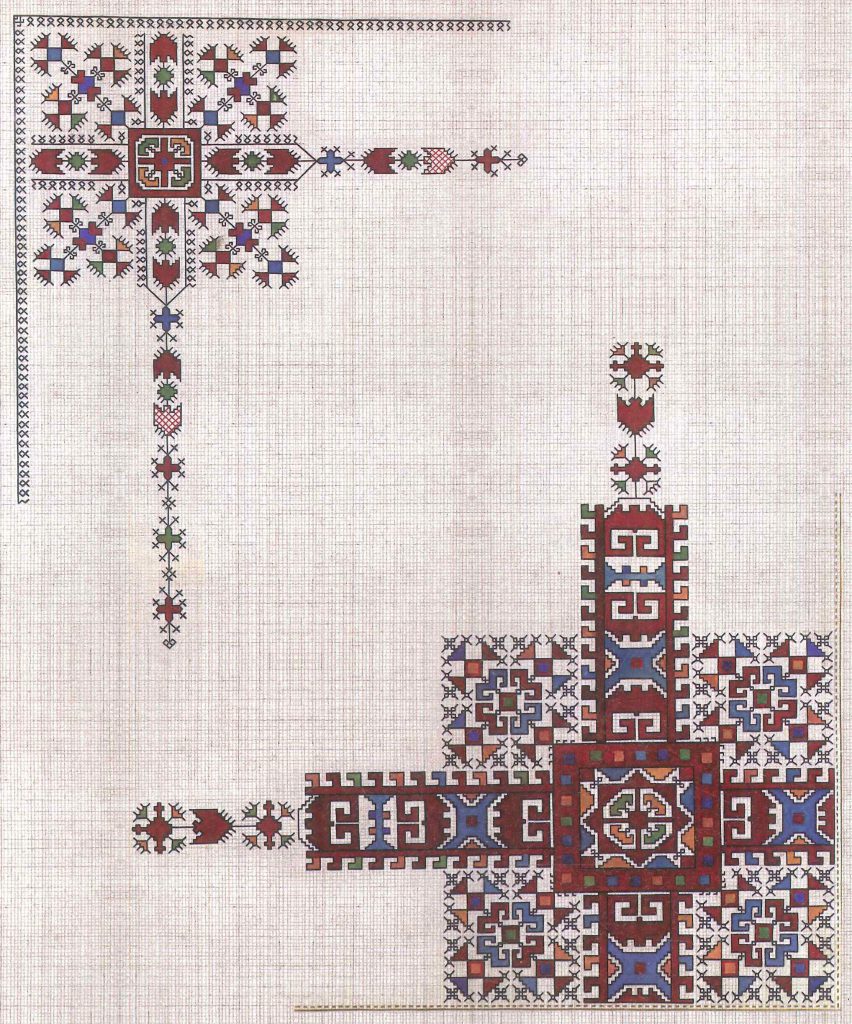

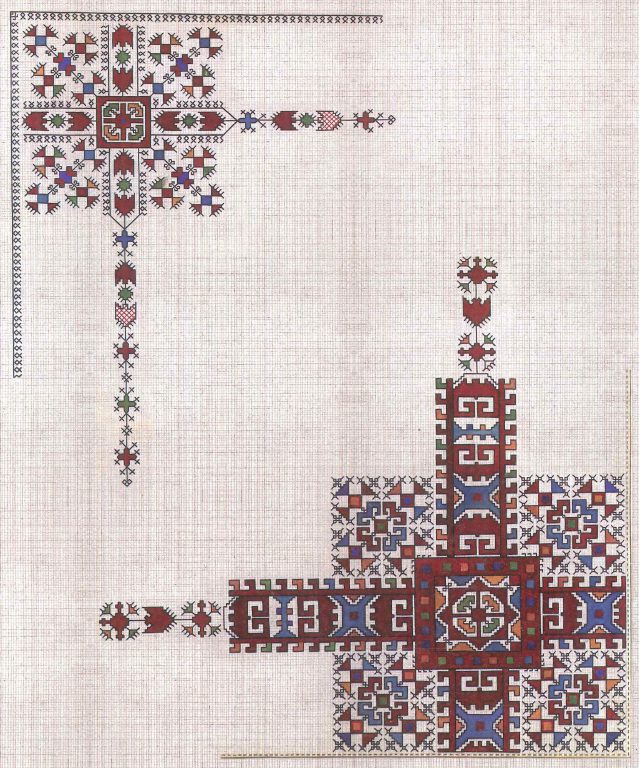

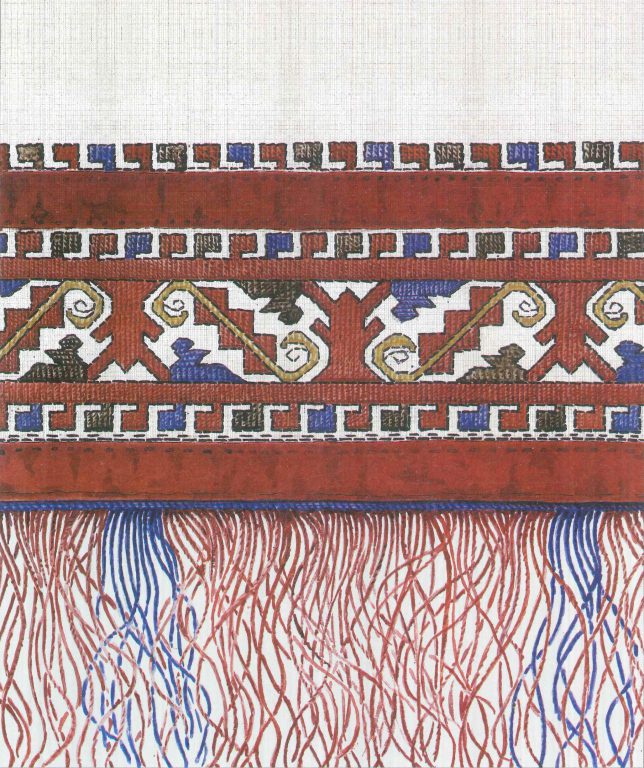

A special cover called şulăk played a significant role in the bridegroom’s attire. A white scarf with a fringe made of scarlet silk, it was folded in a triangle shape and then attached to the back of the outer suit. Two angles of it were sewed on to shoulders, while the third one was left plain. Usually decorated with embroidered geometric patterns, şulăks were used only for the wedding ceremony – this fact emphasises their ritual significance and the importance of the protective ornament. Anton Salmin, an ethnographer and a researcher of Chivash rites and beliefs, claims that in ancient times, şulăks were embroidered only in nights of the full Moon. This might prove the sacrosanct role of the decoration. A scarf was embroidered by a bride: it was one of the presents she gave to her groom’s family in the end of the matchmaking ceremony. This way a girl showed her skills and gave her consent to get married. During the wedding ceremony, when a wedding procession was gathering in the house of her father-in-law, the bride cut the şulăk off and kept it with her.

Ornamental details of the scarf’s angles are akin to the köskö pattern commonly used in the decoration of female shirts, pörkençök bridal veils, and wedding pillows. On scarfs, köskö ornaments were outlined with black threads that made the decoration appear flamboyant on white homemade canvas. This way the pattern acquired a more distinguishable shape and looked like a peculiar mosaic.

THE TECHNIQUE OF CHUVASH EMBROIDERY

Chuvash embroidery is an example of a counted-thread technique: it means that in order to create a pattern, a master should count the fabric threads. It is a very laborious task which demands permanent concentration. There are more than 30 types of stitching techniques in the Chuvash embroidery. They were usually named after other things and natural objects whose form they resembled: ‘a horse’s forehead,’ ‘the pattern of a sorbus tree leaf,’ ‘a stallion,’ ‘deer horns.’ A girl learnt the stitching techniques starting from the simplest ones – whipped and outline stitches. Usually edges of a composition are stitched first, and then the process reaches the centre of a pattern. Every stitch in the Chuvash embroidery has its place and role, and there are special stitches for every article. They differ in their design, technique, complicacy, style, method, and colour. For the decoration of wedding items (such as a groom’s scarf, a bridal veil, or surpan – the type of a head cover), double-sided stitches were used. These are jöpkön (an outline stitch), šulam (a whipped satin stitch), erehle (a spaced cross stitch), isma (a double-sided stitch), çărmalla (a regular satin stitch), kasnă šătakla (a coloured perevit’). Embroidered ornaments made this way looked the same on the both sides of an item.

NOTES

Wedding ceremonies differ from region to region. Researchers try to create the generalised model of wedding traditions, but the real life is more diverse and cannot be narrowed down to any schema. Moreover, it is important to note that the information we have on the life of Chuvashes in the late 19th – early 20th centuries was provided by travellers and – later – ethnographers who were not of Chuvash origin, but were interested in this rich culture.

Works Cited

Matveev, G. B. ‘Wedding’ (in Russian) // The Chuvash Encyclopaedia

Nikolaev, V. V., Orkov-Ivanov, G. N., Ivanov, V. P. The Chuvash Costume from Ancient Times to the Present Day (in Russian). Moscow, Cheboksary, Orenburg, 2002.

Petrov, I. G. Symbolic and Signal Functions of Clothes and Household Objects in Wedding Rites among the Chuvash of the Ural-Povolzhie Region (in Russian) // Etnograficheskoe obozrenie, №1, 2008, pp. 145-162.

Salmin, A. K. The Folk Rituals of the Chuvash (in Russian). Cheboksary, 1994.

Salmin, A. K. System of the Chuvash Folk Religion (in Russian). Saint-Petersburg, Nauka, 2007.

Salmin, A. K. The Traditional Ceremonies and Beliefs of the Chuvash (in Russian). Saint Petersburg, Nauka, 2010.

Sboev, V. A. The Life, History, and Religion of Chuvashes; Their Origins, Language, Rituals, Beliefs, Legends, Et Cetera (in Russian). Moscow, 1865.

Trofimov, A. A. The Ornamentation of Chuvash Folk Embroidery. The Issues of Theory and History (in Russian). Cheboksary, 1977.

Zhacheva, E. N. Chuvash Embroidery = Çăvaš Törri: The Technique, Methods, and Patterns (in Russian). Cheboksary, 2006.