The Popularity of Woodblock Prints

A craftsman carves out a pattern on a wooden block, then covers it with paint and apply the impression to different areas of fabric, thereby ‘printing’ an ornament – this is the process of woodblock printing. This craft has been known in Russia since the 10th century – at that time, cities started to grow rapidly, and trade became a well-established practice. Woodblock printing was a more convenient means of producing ornamented textiles, in comparison to weaving or embroidery that demanded more time and efforts. Colourful yet cheap woodblock prints substituted expensive cloths from abroad, such as Italian velvets, and were very popular. For example, woodblock printed textiles were used to produce both male and female clothes, blankets, tablecloths, and curtains; they were also used to make standards and liturgical items; finally, woodblock printed fabric was a popular material for bookbinding and interior decoration.

Here Gury Nikitin and Sila Savin, the painters from Kostroma, depicted harvesters in pants made of Kostroma woodblock printed textiles

(The illustration from: ‘Yaroslavl’ (in Russian) / Voyeykova I. N., Mitrofanov V. P. – Leningrad, Avrora, 1971. – P. 49)

The Technique of Woodblock Printing

In the 16th-17th centuries, there were two methods of woodblock printing: the impression could be made by either relief, or intaglio printing. The difference depended on the type of a wooden block used.

For the first method, relief printing (known as naboyka in Russian), a pattern on a wooden block would be made convex, and only this convex surface, but not recessed areas, was then covered with paint. When such a block was applied to fabrics, the impression reflected the convex part of a pattern.

The second method (known as vyboyka in Russian) was the direct opposite of the first one, as here recessed areas comprised a pattern. As paint was also applied to a surface only, the print was reversed, with only its background being coloured.

Wooden blocks with curved patterns were called ‘manery’ or ‘tsvetky’ and were made of one large piece of wood. Only solid types of wood were used, such as hazel, pear tree, maple, or birch. A pattern was not curved but ‘beaten’ with mallets and hammers; that is why people who make woodblock prints are sometimes referred to as ‘beaters’ (‘kolotilschiki’ in Russian).

A piece of cloth to be printed might be made of any fabric (from satin to woollen), and be both plain or pre-coloured. However, the most typical kind of fabric used in Russian woodblock printing was linen. The most widespread dye was a black pigment made of soot – it was used to outline a pattern. Then the pattern was coloured with several ‘tsvetky’ (wooden blocks) – they differed in which elements of the pattern were (or were not) curved; so several blocks were used to apply different colours. Small and fine details were coloured manually – this task was usually performed by women.

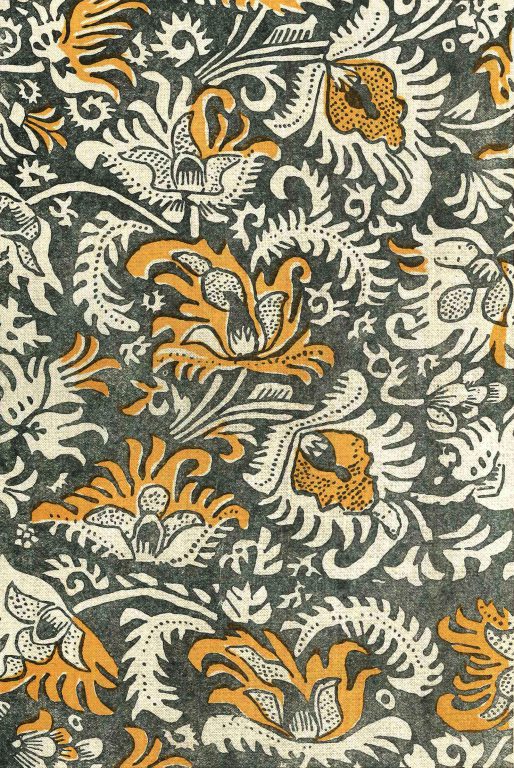

Apart from black, woodblock printers also used red and blue paints – also produced of natural ingredients. The red pigment was derived from cochineals (a species of scale insects) or the rose madder (a plant species), while the blue one was produced from oak bark or woad leaves. Orange (made of minium), yellow (saffron), brown (ochre) shades also were used, although not that often. Sometimes ornaments were additionally decorated with golden or silver powder applied to a glued surface. In the 16th-17th centuries, woodblock printers were more interested in shape and forms of ornaments than in their colours. The majority of patterns of those times were made with the use of only one colour or shade.

There is one more method of woodblock printing – when a special substance resistant to dyes is applied on textiles. This substance, a resist, was called ‘vapa’ or ‘reserv’ – usually it consisted of wax mixed with resin, or clay. It was applied on a piece of cloth with a brush or a stencil; after that the piece was immersed in a vat with dyes. Then the piece would be taken out, and a resist was washed away with water. As a result, the parts of pattern that were covered with this substance retained their original colour.

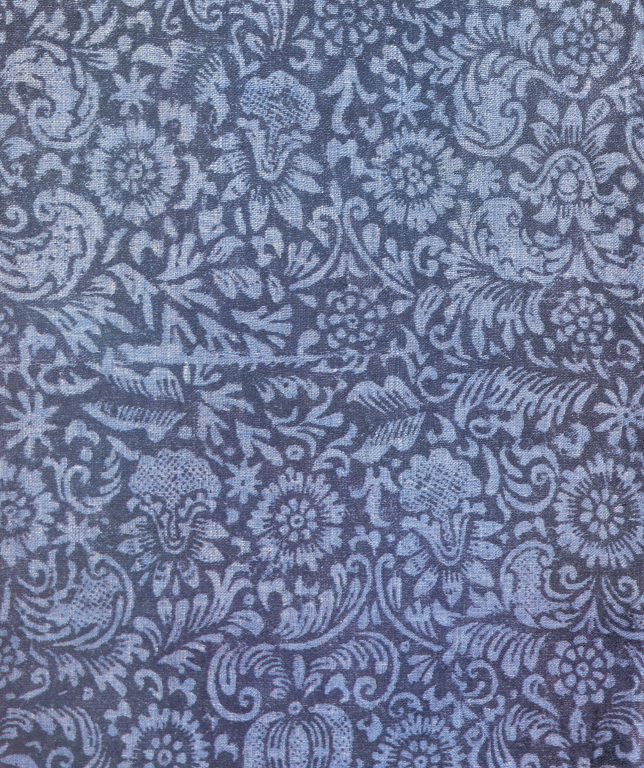

The Ornaments of Woodblock Printed Textiles

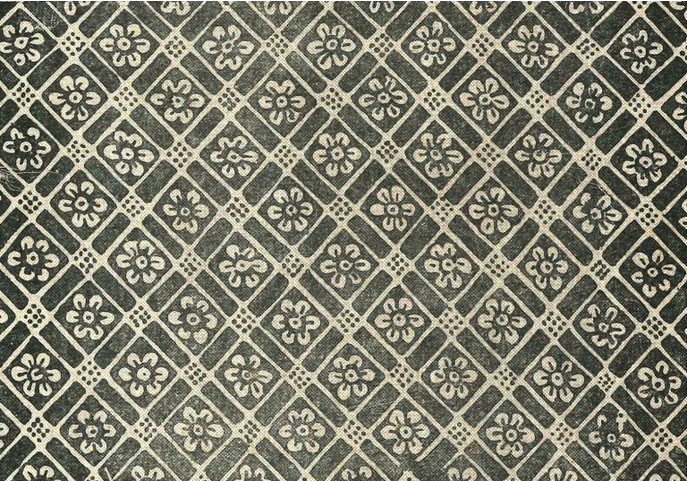

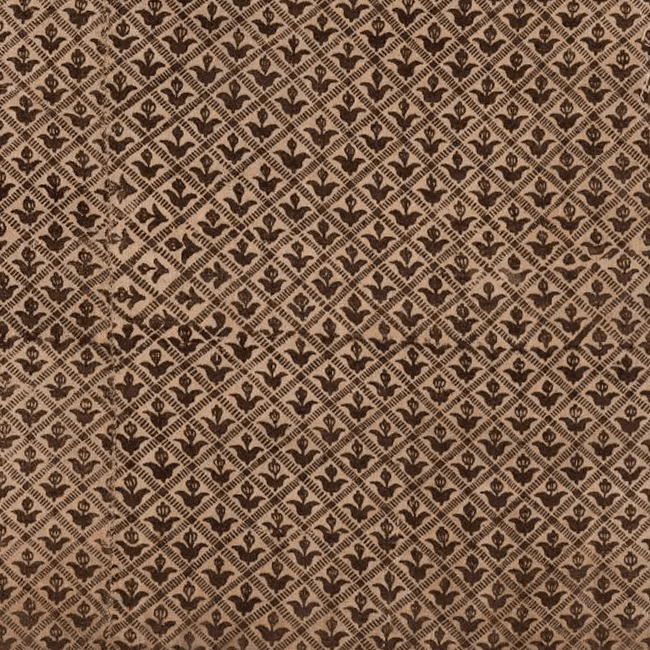

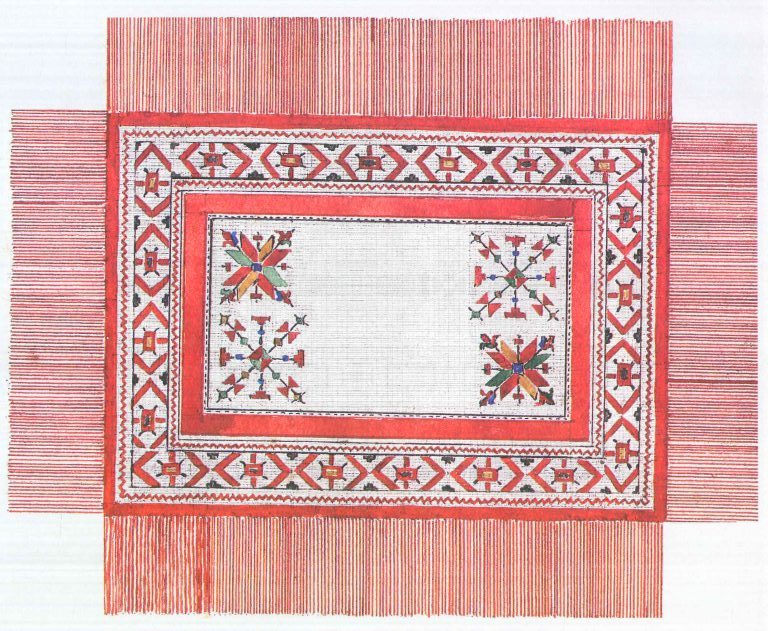

There were two major types of patterns in woodblock printing – a floral and a geometric one, – and quite frequently these two were combined together. Geometric patterns are more ancient: they allow creating dynamic compositions through the combination of simple figures, such as circles, grids, rosettes, stars, et cetera.

It is likely that sloping grids were the earliest pattern to be used in woodblock printing. This type of ornamentation is quite simple: grids are easy to curve, and it was the first pattern that printers’ apprentices learnt to make. Nevertheless, the background of woodblock prints was often decorated with additional small dots, checks, and lines. Different regions of Russia had their own favourite motifs: for example, woodblock printers from Ivanovo Oblast preferred dots, while craftsmen from Kostroma loved to make straight, transverse, and diagonal lines.

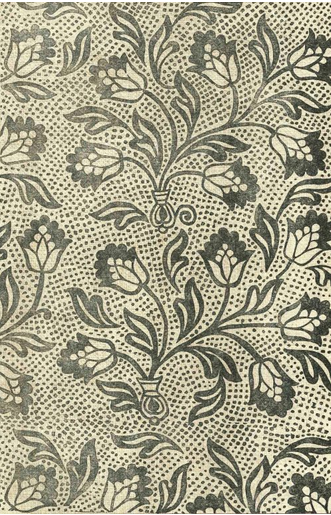

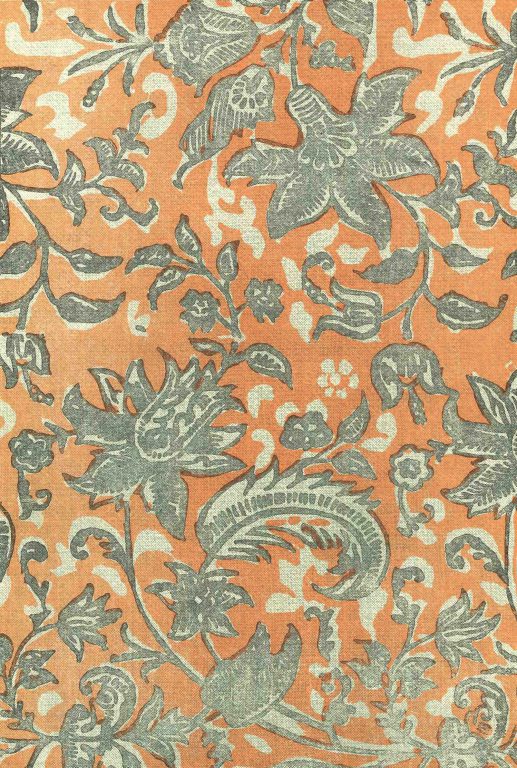

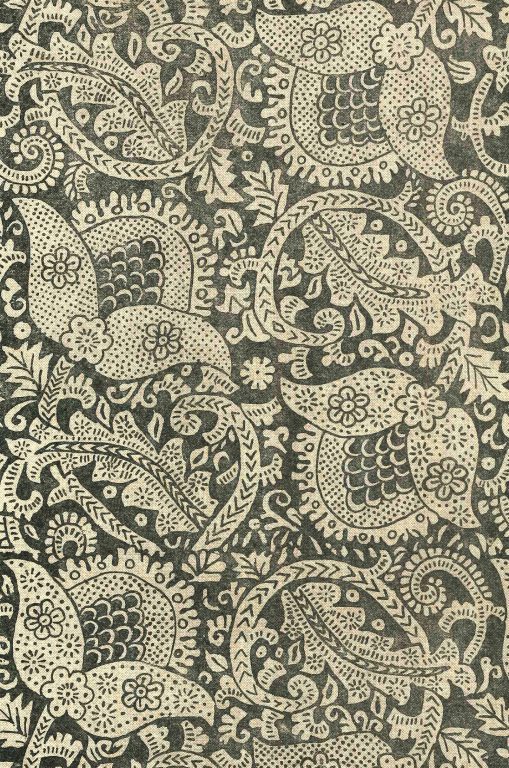

Monumental, sumptuous forms are a defining characteristic of floral patterns of the 17th century. Artisans frequently decorated textiles with baroque scrolls, giant fruits, and flowers with thick stems, large leaves and stamens. The flowers depicted could be both a figment of the printer’s imagination or real plants typical for local nature. For example, a part of the marquee of Tsar Alexis of Russia is decorated with woodblock printed images of blackberries, sunflowers, and knapweeds, with leaves of acanthus and stems shaped into twisted braids. However, Russian woodblock printers sometimes used more unusual motifs, such as images of pineapple or pomegranate. Nevertheless, surrounded by other patterns, these elements looked natural and did not ruin the overall composition.

XVII века

The colour scheme, images of flowers, and the colouring of background reveal the influence of Arabic traditions

The Borrowing of Patterns

Woodblock printers had various sources of inspiration: they borrowed ideas not only from nature, but also from other crafts – embroidery, lace making, rug making, book illustration, stone and wooden architecture. Like in other branches of the applied arts, mythological or fairy-tale motifs were also quite common in Russian woodblock printing: they included images of gryphons, the tree of life, or Sirin – a paradise bird with the face of a woman, wearing a crown on its head. The imagery of Sirin in stone architecture can be found, for example, in the exterior sculpture of Saint George Cathedral of the 13th century in Yuryev-Polsky – one of the centres of woodblock printing, – or in the sculpture of the Cathedral of Saint Demetrius in Vladimir.

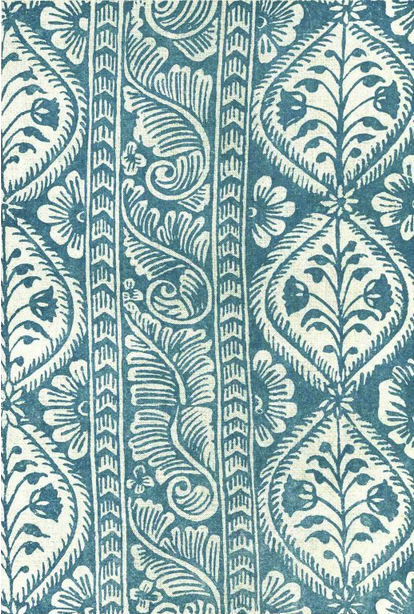

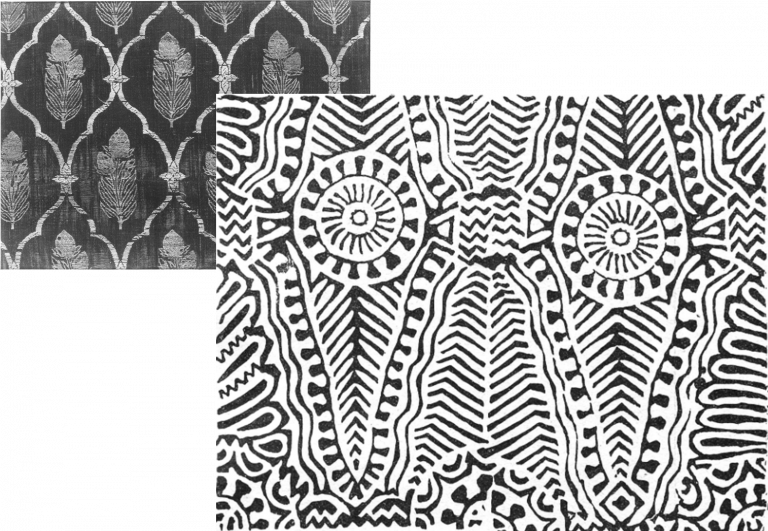

On the right: woodblock printed cloth, 17th century

Some stylistic methods were derived from textiles brought from Italy or the Eastern world: Byzantium, Persia, China. However, Russian woodblock printers did not copy patterns from abroad, but reinterpreted them in accordance with local traditions: some ornaments were altered or supplemented with local motifs, while some were not used at all. The roughness of Russian cloths, especially linen, also affected the overall composition.

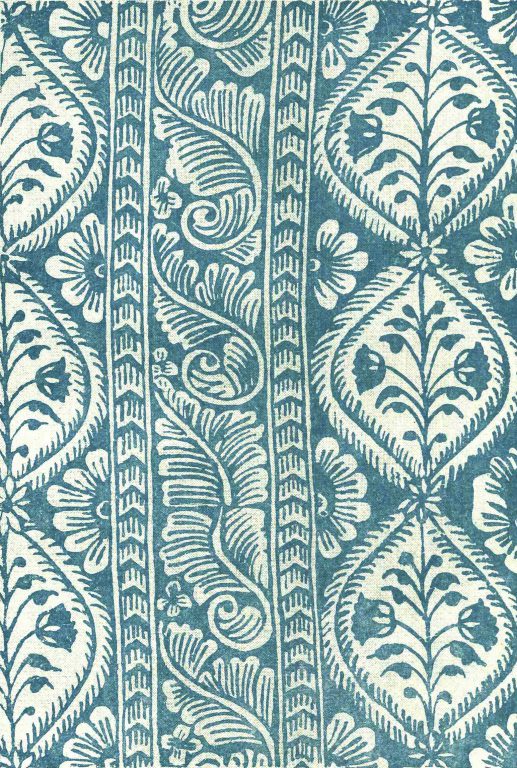

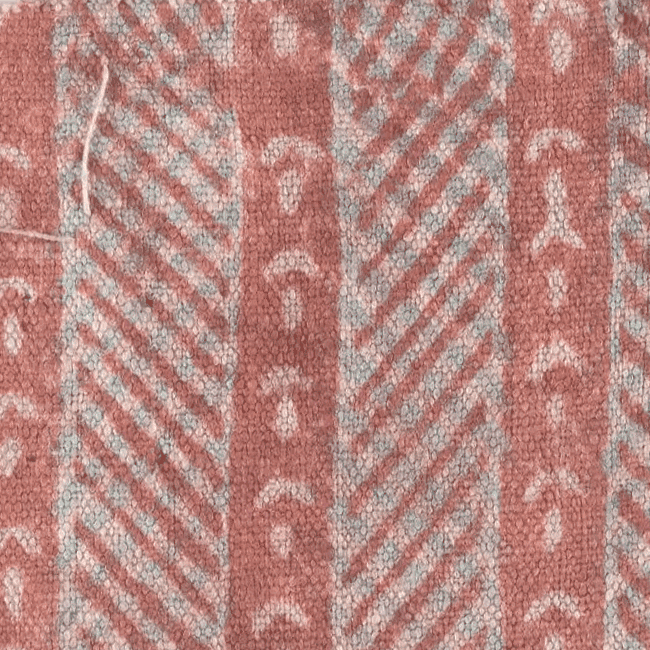

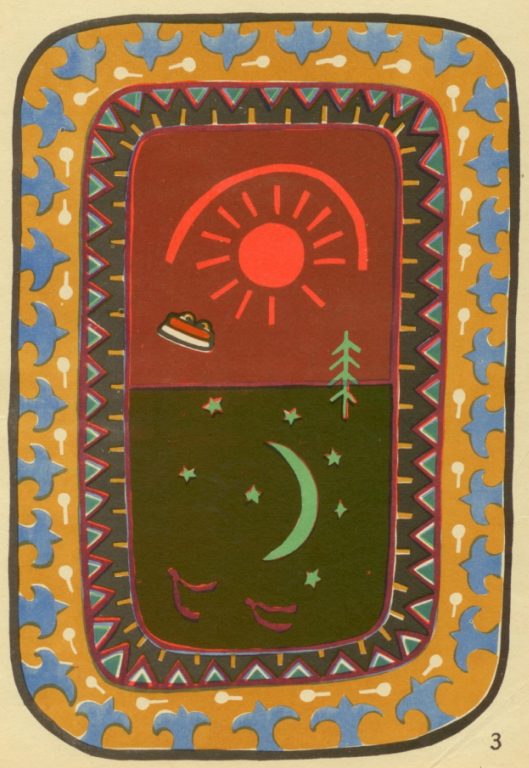

On the Gilan courtyard in Astrakhan, merchants from Perisa used to sell silk cloths with a typical oriental pattern – alternating bright and dark stripes, sometimes supplemented with small flowers. This type of composition became popular in Russia and was known as ‘roads’ (Russian: ‘dorozhka’). Edgings of a textile with this pattern, however, could be decorated with traditional, local ornaments.

(The illustration from: ‘Oriental and European Textiles in the Collection of the State Historical Museum’ (in Russian) / The State Historical Museum – Moscow: Vneshtorgizdat, 1985)

In the centre: the fragment of a curtain with a woodblock printed pattern, 16th-17th centuries

On the bottom: the fragment of a gingerbread board, late 17th century.

The ‘road’ pattern borrowed from the Eastern world is combined with the imagery of a double-headed eagle and peacocks inspired by Russian gingerbread boards

(The illustration from: ‘Oriental and European Textiles in the Collection of the State Historical Museum’ (in Russian) / The State Historical Museum – Moscow: Vneshtorgizdat, 1985)

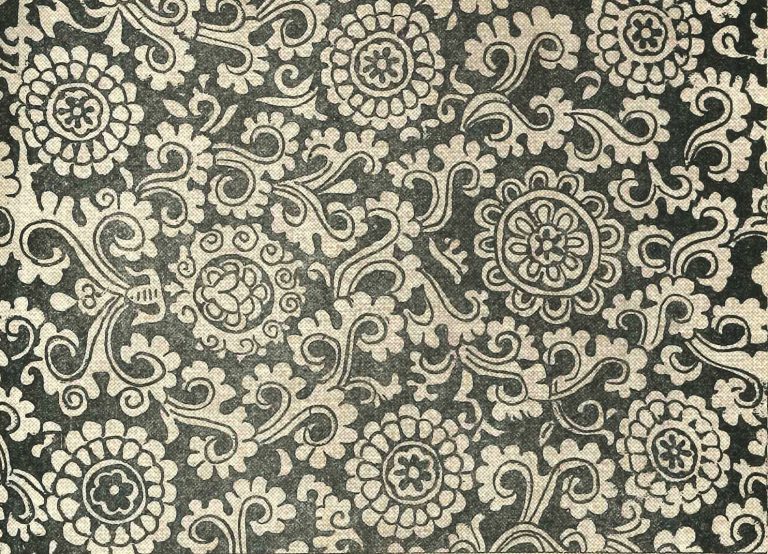

On the right: the fragment of a woodblock print, late 17th – first half of the 18th centuries

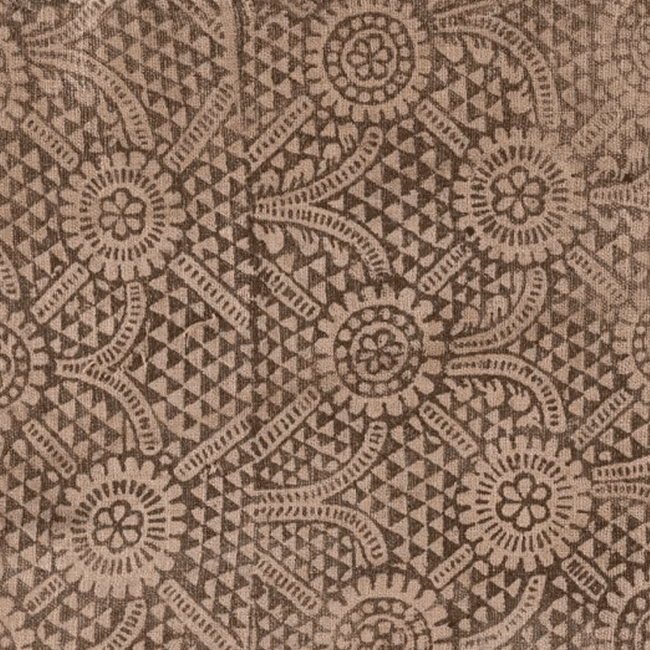

Some patterns that might resemble thin slabs were indeed inspired by Iranian ceramic tiles. The elements of these ornaments are comprised of alternating framed images. Reinterpreting these foreign motifs, Russian artisans tended to create as dense composition as possible, leaving no blank areas. In the image below, the repetitive motif (also known as ‘rapport’) consists of large rosettes framed with wave-like rhombi. Centres of these rhombi are decorated with jagged lines that resemble willow leaves.

(The illustration from: The Metropolitan Museum of Art Collection, Website)

On the right: an impression made with a wooden block (‘manera’), 16th-17th centuries

Russian woodblock printing of the 16th-17th centuries is characterised by a striking paradox. In contrast to other branches of the applied arts, there were no foreign woodblock printers who would teach Russian artisans. Nevertheless, in woodblock printing the influence of foreign cultures was more obvious than in any other craft.

Works cited:

- Voyeykova I. N., Mitrofanov V. P. Yaroslavl (in Russian). Leningrad: Avrora, 1971

- The State Historical Museum. Oriental and European Textiles in the Collection of the State Historical Museum (in Russian). Moscow: Vneshtorgizdat, 1985

- Plotnikova M. V. Relief Printing (in Russian) // Russian Traditional Crafts in the Collection of the State Russian Museum. Leningrad: Khudozhnik RSFSR, 1984

- Sobolev N. N. Woodblock Printing in Russia (in Russian). Moscow, 1912

- Yakunina L. I. Russian Woodblock Printed Textiles of the 16th – 17th Centuries. (in Russian) // Pamyatniki Kultury, Vol. 8, 1954

- The Metropolitan Museum of Art Collection (link)

Author: Valentina Bogdanova

The article will be further supplemented with new information on the Russian woodblock prints of the 16th – 17th centuries found in other sources, and with new images added to the collection.