The article is created in cooperation with historical-geographical society “Dzurdzuki” and is based on the materials from the book “Ingush National Ornament.”

FELT CARPETS OF INGUSHETIA

Among all the domestic crafts, woolcraft had a special place in Ingushetia. This was largely due to the fact that in highland areas, it was easier to breed sheep and goats – the main sources of wool.

Handmade felt carpets easily tolerate dampness and dry air – these useful characteristics and their decorative qualities made them a necessary everyday item for many nations. Felt rugs attracted attention of various travellers and researchers of the life of the Caucasians as early as in the 19th century. Otto Marggraf wrote that Caucasian felt is “dyed in different colours and covered with ornaments; or multi-coloured felt pieces of fancy shapes are cut off and then sewed together in patterns. The decoration of these carpets demands great skills and taste.”

In his article “Cities, villages, dwellings,” Veniamin Kobychev, the researcher of Caucasia, described the everyday life of the peoples of the North Caucasus. He wrote that the interior and furnishment of highlanders’ houses were simple, and the location of every item was defined and determined by superstitions. Pride of place was taken by a high-back sofa which was covered with “a carpet, mat, or felt, depending on owner’s wealth.”

In some villages in Ingushetia isting* (* – here and after the asterisk sign refers to the list of terms which can be found in the end of the article) and khijttafertash* carpets were made not only for domestic use, but also for sale. The lowland villages of Barsuki, Plievo, Altievo, Gamurzievo, and the highland village Goust were the well-known centres of felt carpets production in Ingushetia from the second half of the 19th century and until the beginning of the 20th century.

The technique of felt carpets making in Ingushetia was similar to the techniques used in other parts of Caucasia. For centuries, felt had been known in the Caucasus for its healing properties; it was integral to the design of various domestic items and clothes, and was widely used for the heat insulation of houses. That is why having sheep breeding farms was so important. According to Eugeny Krupnov, “in ancient times, the particular breeds of small sheep and goats were especially popular. Some of them are now known as aboriginal breeds and are still bred by the Tushetians (Tush sheep), as well as by the Vainakhs (the Chechens and Ingush) and some other peoples of highland Dagestan.” The breeds mentioned above refer to small sheep with long wool. Fibres of long wool stick to each other better than those of short wool – this capacity contributes to the durability of felt.

THE ROLE OF WOMEN

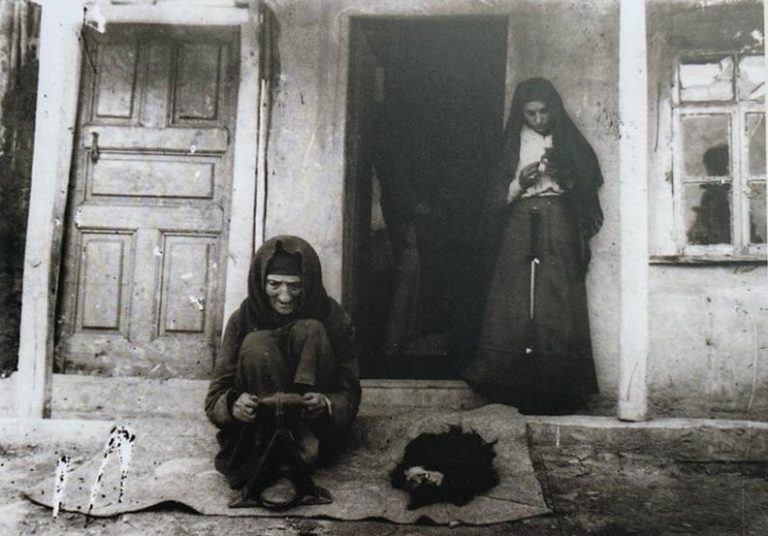

The making of felt carpets was a meticulous and laborious process, and it was executed only by women.

Every woman had been learning the technique of rug making from her early youth. A girl would usually make carpets as her dowry, as rugs were deemed valuable presents for her prospective father-in-law and husband. Isting carpets were mainly used to decorate guest rooms, while more austere rugs without ornamentation would cover tapchans (a type of a large couch combined with a table). Every woman and every family used their own exclusive ornaments which were imbued with particular symbolic meanings. The decoration patterns embodied in leather templates were handed down from mothers to daughters (some families keep these templates even today).

Our respondent, 93 y.o. Boby Khanieva, says that if there was plenty of wool, women would usually card and spin it collectively (but young and mature females worked separately). This practice is known as belkhij (this term describes uncoerced community activities). The most vigorous and active person acted as a coordinator: she would allot a share of wool to each woman and maintain a playful, fancy atmosphere of the working process. There is even a folk adage which describes this labour-intensive practice: “For one person such process is akin to death, for two it is hard work, and for three it is entertainment.”

When belkhij was nearing completion, young men usually came to the working site and organised the lovzar dance. In this situation, one of the women wouldplay traditional melodies on a squeeze-box, and young people would make jokes and set to each other sophisticated riddles which often did not have correct answers. All these simple tricks helped to ease any hard work.

“The mutual understanding between all workers was necessary to produce highquality felt. It was to be done with care and love, protected from bewitchment,” – notes Tamara Shavlaeva.

THE TECHNIQUE OF FELT CARPETS MAKING

Sheep were sheared in springs and autumns, but felt was usually made out of autumn wool. Sheared wool underwent fulling in river waters, and then women dried and carded it. After that, wool was felted and dyed.

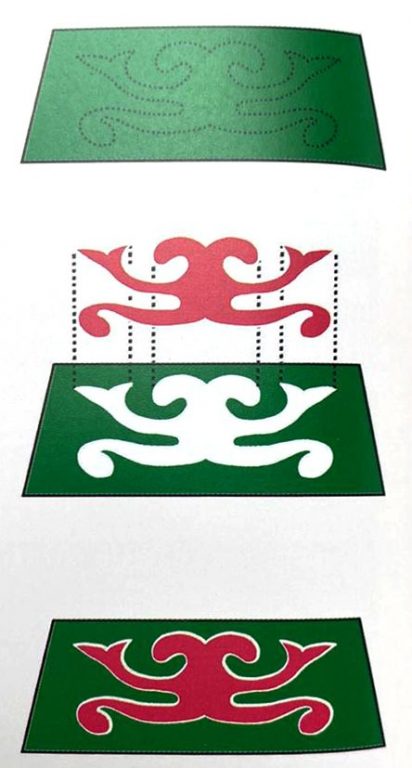

The first step of the felting process started with wool being laid in three layers on a piece of fabric. These layers were tamped with a stick and then sprayed with whey for better grip. After that wool was rolled up, and each roll was put in a warm place for one night. Then the material was rolled over and over again several times, washed with water in an artificially made duct, rolled up and left to dry for several days. Carpets were unrolled while wet to make them dry up. This way several felt pieces were produced and then dyed in different colours. Ivan Shcheblykin, the researcher of Caucasia, notes that “bright yellow, orange, red, bright green, and some other hues” were the most popular tones of Ingush felt carpets. According to ethnographical research, red colour and its shades were popular not only in felt carpets making (where they were used as basic colours), but also in decoration of clothes and headwear. It is likely that red colour conveyed some magical sense, as it was supposed to confer protection against hex and the evil eye. Many other nations of the Caucasus also believed that red has magical properties: for instance, it was said that this colour could protect against smallpox and measles.

The next step was dying. Large pieces of felt were dyed entirely in different colours; durable paints used for this purpose were often made of local plants. For example, black pigment was derived from sea-lavender (limonium), foxtail pricklegrass, glossy buckthorn, the bark of buckthorn and black alder, as well as from birch bark. Yellow paint was made of maple leaves (acer laetum), smoketree, and from stems and roots of barberry. The bark of buckthorn and willow, and the leaves of nettle and smoketree were known to contain brown pigment. Flowers of gentian and Caucasian belladonna, as well as berries of bilberry were used to obtain violet pigment. Thin-leaved peony (paeonia tenuifolia) and berries of bilberry helped to derive green pigment, while bark of buckthorn, roots of sorrel and bilberry berries – red pigment. The carpets werealso dyed with the help of nettle and beech nuts. Of course, once aniline dyes were introduced to Caucasia, the process of dying was facilitated. But whereas these new pigments allowed to obtain diverse and very bright colours, Ingush women continued to follow traditional colour patterns while making felt pieces. This is explainable: the resistance to fading could only be guaranteed by plantbased pigments.

However, not everyone could make their own paints due to the complicacy of the process. Therefore, in almost every village there was a person who collected roots, stems, leaves, and berries of different plants during the year and then produced paints from them. This person could also dye some woollen or fabric pieces for money. Mukharbek Akhilgov, the Elder of the village Goust in the highland region of Ingushetia, remembers an Ingush woman who lived in Angushta in the first third of 20th century (currently this village is known as Tarskoye) and dyed felt carpets: “She could obtain very beautiful colours, but she never told anyone her secrets.”

In the village of Mochkhi-Yurt (now Bazorkino) there was a man called Musi Shakhmurziev who specialised in the dying of felt goods. Skillful dyers could produce bright, colourful, and subdued shades at the same time: white, black, dark and light blue, green, brown, yellow, orange, grey, red, beige, as well as silver and gold, or ash and mouse grey, or even mixed tints (black-and-white or spotted patterns).

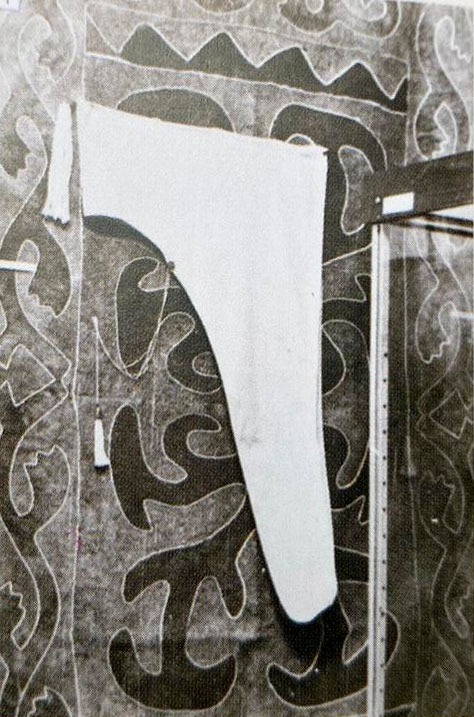

The ornaments were cut out with the help of calfskin templates that passed down from generation to generation. This fact and the deep semantic meaning of the ornaments explain why the decoration of Ingush felt carpets has been sticking to archaic patterns.

After the soaking stage was completed, all parts of a carpet were dried in shadow. “After all the parts are dry, the final fitting is done, and the pieces are sewed together,” – writes Ivan Shcheblykin. “Every single piece of the pattern is trimmed with white woollen inkles.”

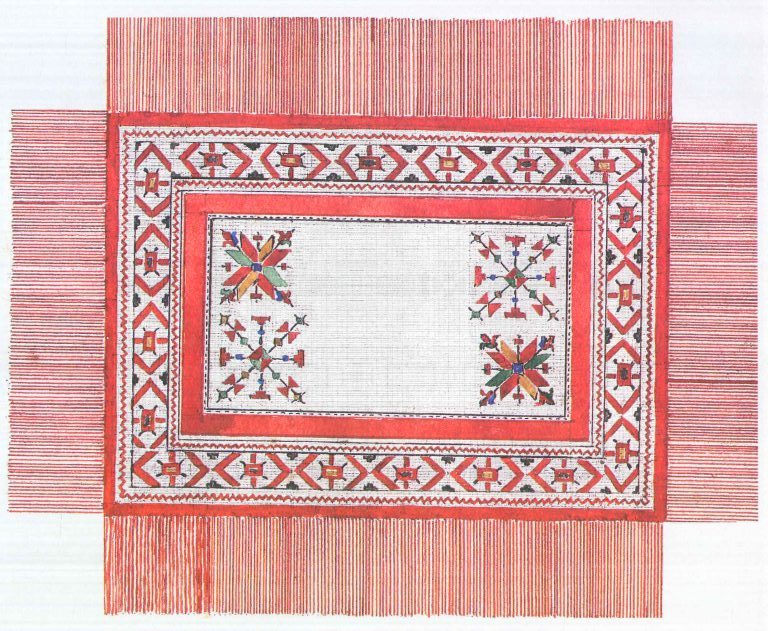

Every element of the ornamentation was trimmed with an outline; the edges were decorated with pieces of fabric sewed to it, or with fringe.

THE MEANING OF ORNAMENTATION

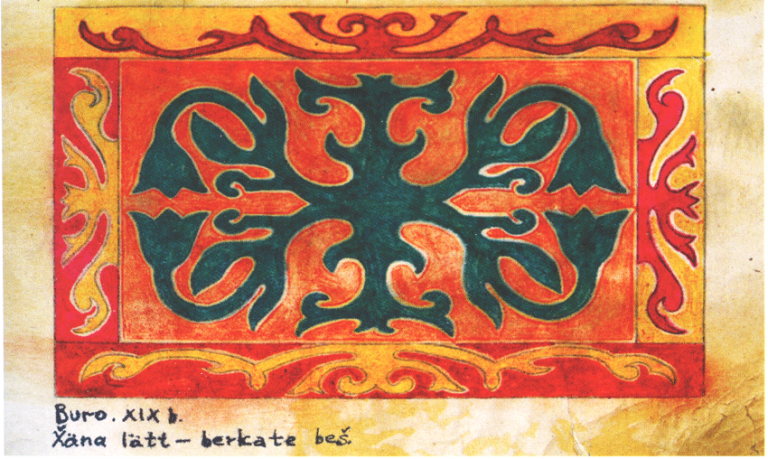

Vera Ivanovskaya describes Ingush ornaments as symmetrical and full of floral elements; she adds that it can be characterised by “rhythmicity and the ‘wideness’ of the rhythm.”

Lidia Fokina notes that in the more recent examples of Ingush felt carpets one can notice “the signs of more and more concrete thinking: figural elements (images of deer, horses) are becoming integrated into zoomorphic, hornlike, or (conventional) floral ornaments.”

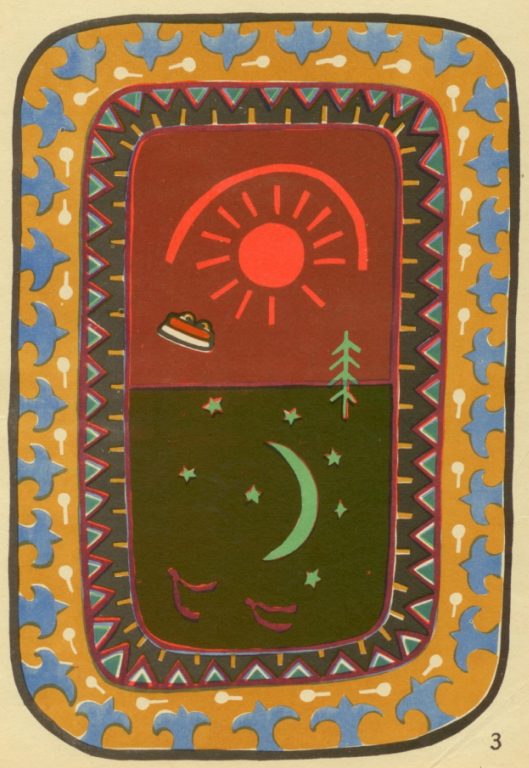

V. Tataev and N. Shabanyats note that the decorative compositions of carpets consist of “stylised ornaments, symbolic figures of a sun, stars, crescents, deer horns, circles – both full and irregular ones, – rectangles, rhombi, swirls, and other motifs that are harmonically combined to comprise a well-rounded artistic image.” Ingush carpets are characterised by “the conciseness of the artistic medium, austere rhythmical composition, outlined conventional patterns, their abundance and decorativeness.”

The stylised figures of animals are the most common element of Ingush felt carpets. For instance, deer horns were the most widespread pattern to be used by Ingush rug makers, and it could be found in all areas of the North Caucasus. The figure of deer had a particular meaning in the cult beliefs of the local people.

Floral patterns of Ingush carpets are usually located in the centre of the rug’s composition and are represented by tulip-shaped flowers, dainty buds, curls and outgrowths that look like bindweed when combined with flowers; sometimes trefoil leaves can also be found.

Many astral and anthropomorphic pictorial elements which are in the core of the Ingush ornamental tradition can be dated back to the pre-Islamic era: examples include figures of snakes or wave-shaped and zigzag lines.

Solar symbols can also be frequently found in Ingush felt carpets, mostly in the compositional centres of rugs’ ornamentation. The image of a sun, as well as waves and triangles had a magical meaning. The role of these sacred symbols in the culture of Ingush people and Ingush carpets demands special attention. Vladimir Markovin wrote about these symbols the following: “It is possible that some of them expressed concrete ideas, in other words, they were pictograms.” Markovin also conjectured that “all these pictures were intended to helphighlanders in their uneasy daily life;” they served as “invocations, entreaties, amulets.”

After the Ingush converted to Islam, the ornamentation of felt carpets gained new elements, such as ‘rosettes’ – stars, crescents, lotus or tulip-shaped flowers.

THE SONG OF PYATIMAT

There is a song in Ingush folklore which is called “The illy of how the tower was built” (illy is a term which refers to the type of Ingush epic songs). This song tells the story of an Ingush woman Pyatimat who created fancy ornaments for her carpet, inspired by the beauty of “mountain meadows,” heavenly body – the moon, and “stars, her friends.”:

“…After that, they started to feast, laying a large felt piece on the grass,

A felt piece made by Pyatimat and the six daughters of hers…

Many nights Pyatimat has not slept, with her eyes being closed she lay,

And her young star was sailing the unchanging blue sky,

And her moon was the highest in the firmament.

Surrounded by small dancing stars, her friends,

Old Pyatimat was roaming around mountain meadows,

Picking up flowers and herbs that she needed so badly!

Three times Pyatimat laid pieces of felt one on another,

With her hands dry as eagle’s feet, she drawn an ornament she saw in her dream,

And a knife touched the felt piece, scrunching, as ploughs in highland fields, –

Her dream came true, it turned into the bright rug of the valley…

Pyatimat was cutting piece after piece, whispering her dreams,

And her six daughters were nodding in tune…

For twelve days these six maidens were sewing

While old Pyatimat told them what she was doing

As she was young… By the thirteenth day, the felt rug was ready,

Pyatimat closed her eyes and fell into the dark, as a moonless night, eddy…

For twelve days the six maidens were sewing,

To outline the edge of the ornament with white fabric.

Then eight young men unfolded the rug made by old Pyatimat:

Behold! The star of her youth spread out five golden arms,

And the young moon, Pyatimat, is here – she flows by and charms,

The young moon, Pyatimat, and six stars next to her sail the sky,

The six stars of her six daughters flow, with sparkling eyes,

The garland from Hud-Huderesh enlaces them, while the stars have created a path –

Flowers, deer horns, and the herbs of mountain valleys – all are there,

All are embraced by the mountain dusk with its bright and crimson lines,

While the spring of life was watched by two hundred and sixty eyes!”

…………………………………………………………….

*Classification and Terminology

There are several types of felt carpets: isting, fertash, and khijtta-fertash.

Isting is a term which refers to felt carpets with sewed-on patterns made of inkles or leather of different kinds. Isting carpets (plural istings) were used to cover beds, tapchans, chests, et cetera. It is still not clear why this term has been used to describe ornamented felt carpets, as its etymology is not known. It is possible though that the term isting is somehow related to istij – this word refers to married women (and it was married women who were predominantly engaged in felting processes).

The term fertash describes coloured pieces of felt without any ornamentation. They were commonly used to cover surfaces of tapchans or wagons, and also as floor carpets and bed mattresses. Fertash felt is very firm and steady, and it is usually thicker than felt for istings.

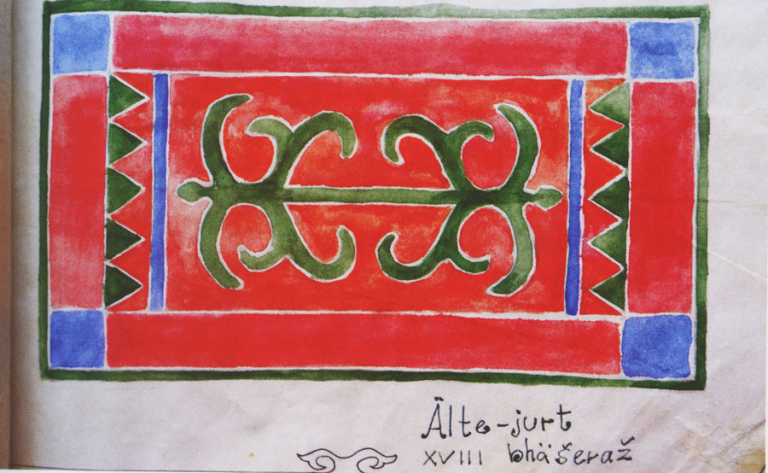

Khijtta-fertash are felt carpets made of several pieces of coloured materials that comprise an ornament. They are sewed together and decorated with white inkles that outline the edges of patterns. These carpets were not used on daily basis and were hanged on walls as a means of decoration.

There are many words in the Ingush language that refer to felt*: *the terms are given in Ingush with phonetic script.

- The word “кIувс” [kʲʼuws] means “carpet” (felt or woven).

- The word “бIегIинг” [bʲɛɡinʁ] means “felt,” whereas the piece of felt is referred to as “бIегIинга чIегилг” [bʲɛɡinʁɑ ͡tʃʼɡilgj].

- “Ферт” [fɛrt] is the term to describe not only felt carpets, but also burkas made of felt.

- “Хетта-ферта” [χɛttɑ-fɛrtɑ] is the word which describes felt carpets made of several patterns which are sewed on one to another. This term literally means “the combined pieces of felt” (as khetta [χɛttɑ] means “combined,” “sewed”).

- “Истинг” [istinʁ] – large pieces of felt, felt rugs (istings).

Other terms:

- “Инз” [inz] – inkles made of white threads. They are used to outline patterns on the isting carpets.

- “Къенж” [qʼjɛnʒ] – short fringe which is used to trim sole-coloured felt carpets.

- “Энж” [ənʒ] – 4-5 cm wide inkle which is used to trim all the sides of a carpet with the inner stitches.

- “Кха-йокъ” [qɑː- joqʼ] – alkali. It was needed to clean the autumn wool of sheared sheep, to wash out fat and sweat from do (d) (animals’ fatty spew, see below). Alkali was produced out of several ingredients: yellow clay, wood ash, and animal fat which were taken in proportion 1:1:1 and boiled for approximately 35-40 minutes (while 1,5-2 hours are needed to produce soap).

- Do (d) – fatty spew which accumulates in the sheep’s wool before the autumn shearing.