-

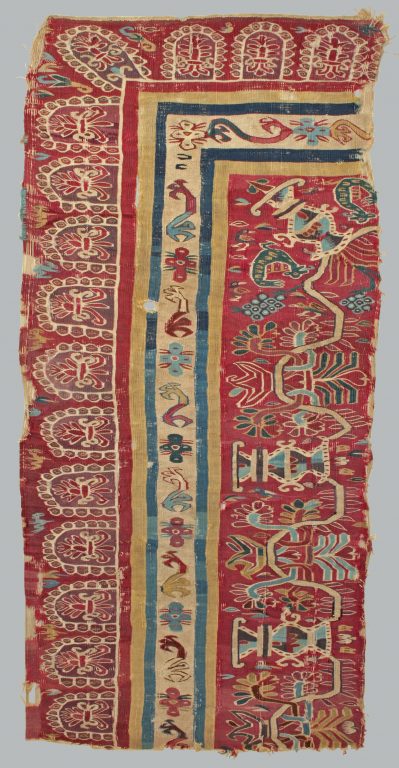

Objecttextile (towels, carpets, etc.): Tapestry fragment

-

Type of arts & crafts

-

MediumCamelid hair, cotton

-

SizeH. 48 x W. 23 in. (121.9 x 58.4 cm)

-

Geography details

South America -

Country today

-

Datelate 16th-17th century

-

CulturePeruvian

-

Type of sourceDatabase “Metropolitan Museum of Art”

-

Fund that the source refers toMetropolitan Museum of Art

-

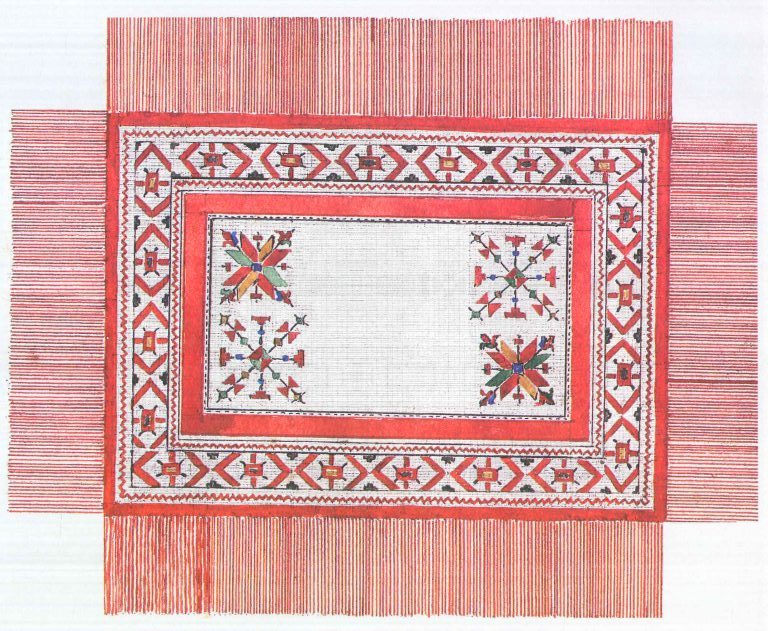

This lively and colorful fragment was once part of a large, tapestry-woven table cover, bed cover, or wall hanging. Its size, proportions, and basic organization may have been similar to the large Peruvian tapestry with figurative scenes in the collection of the Metropolitan (56.163).

The composition of the fragment consists of a series of major and minor borders, separated by guard stripes. Throughout, red is the predominant color; this is typical of Andean textiles both before and after the sixteenth-century Spanish invasion, and was probably achieved through the use of dye extracted from cochineal, an indigenous American insect. Off-white, yellow, blue, green, and purple also appear. The fragment’s outermost minor border consists of a red ground decorated with off-white, oblong scallop designs meant to imitate bobbin or needle lace (bobbin lace is made by braiding and twisting together lengths of thread, usually linen or silk, wound onto bobbins, while needle lace is made using a needle and thread). The interior of each scallop has a purple ground with an ornament, in red outlined with white, reminiscent of a fleur-de-lis.

In the interstices of the scallops are flora and fauna native to the Andes: yellow and light-blue ñucchu flowers (members of the Salvia genus), viscachas (Andean rodents that are part of the chinchilla family), and, along the warp heading, a bird. Red ñucchu flowers, including Salvia tubiflora Smith and Salvia dombeyi Epl, were sacred to the Inca; both Salvia dombeyi Epl and another red ñucchu, Salvia oppositiflora Ruiz and Pávon, have been used in Holy Week and Corpus Christi processions in Peru and Bolivia since the viceregal period (the mid-sixteenth century to the early nineteenth century). There are several related Andean Salvia species with blue flowers, though they have no known ceremonial or sacred uses. The weaver probably intended to evoke red ñucchu flowers, choosing non-standard colors for aesthetic reasons: yellow and blue provide a pleasing contrast to the border’s red background.

Moving inward, toward what would have been the center of the textile, we find a narrow, second minor border with a set of narrow guard stripes on either side. On the outer edge there are three stripes in red, yellow, and blue and on the inner edge there are two stripes in blue and yellow. This second border features an off-white ground and alternating quatrefoil and inverted s-shaped designs in blue, off-white, yellow, and red. The quatrefoil, a design popular in Gothic and Renaissance Europe, entered the Andean decorative vocabulary after the Spanish invasion. Here, the quatrefoils can be read as abstract designs, though they also suggest a bird’s-eye view of a four-petal flower. In addition, the weaver of the textile, who was probably a native Andean, may have been attuned to the quatrefoils’ affinity with the four suyus, or geographic and cultural regions, of the Inca empire, Tahuantinsuyu. The superimposed dots at the center of each quatrefoil would therefore evoke Tahuantinsuyu’s capital city, Cusco, which was, for the Inca, the center of the world. This association should not be understood as an explicit act of subversion on the part of a weaver and patron who were subject to Spanish rule; rather, it speaks to the endurance of Precolumbian Andean culture—despite Spanish opposition—in the viceregal era.

At either end of the s-shaped designs are hooks, usually three-pronged (one is two-pronged, though this may have been a mistake on the part of the weaver). The s-shapes are executed in two contrasting colors, one color for each half of the design. These shapes are reminiscent of the inverted s-shaped designs seen on several viceregal Peruvian women’s mantles, called llicllas (including one, 1994.35.67, in the Metropolitan’s collection). These designs are most likely an abstraction of the scrolling, flowering vine (a European motif) seen, for example, in the borders of a viceregal Peruvian tapestry in the Museum of Fine Arts Boston (04.123).

The innermost area of the fragment, with its vase and scrolling vine motif, is most likely the main border; the fragment’s affinity with a large tapestry in the Brooklyn Museum (40.134), which also features an imitation-lace border, supports this assertion. This area of the fragment consists of a red ground decorated with urns or vases bearing blooming flowers and plants; these vessels are connected to each other by a leafy, scrolling vine. Interspersed around the urns are bunches of berries, flowers, birds, and two fantastical, winged, dragon-like creatures flicking their blue tongues. The urns and vines are European motifs, and testify to the presence of Renaissance ornament—in architecture, prints, textiles, and decorative objects—in sixteenth- and seventeenth-century Peru.

The visual etymology of the dragons is more complicated. Dragons and basilisks (mythological monsters often depicted with the head, body, and clawed feet of a bird, wings—sometimes feathered, and sometimes reptilian—and the tail of a serpent) appear in European architectural decoration, manuscripts, and prints from the medieval through the early modern periods. The creatures on the fragment, however, most closely resemble not these European precedents, but rather the basilisk figures seen on some Peruvian keros, or ritual drinking cups. While such creatures appear only on keros made after the Spanish invasion (and are therefore associated with introduction of European imagery), scholars have also noted their affinity with the amaru, a mythological Andean winged beast with the head of a feline, bird-like claws, and a serpent’s tail. In fact, the beasts on the textile fragment may have been intended, not unlike the quatrefoils of the second border, to simultaneously evoke European and Andean motifs. Finally, it is possible that the weaver drew additional inspiration from Chinese textiles, especially those made in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries for the Iberian and greater European market; such textiles also arrived in Spanish America on the large ships, called galleons, that sailed between the Spanish-controlled Philippines and Mexico beginning in the late sixteenth century. Indeed, the open mouth, extended tongue, and claws of the creatures in the fragment are reminiscent of the paired dragons in the central field of a Chinese export coverlet in the Metropolitan’s collection (1975.208d).

Although the fragment’s flower, bird, and viscacha motifs do not appear in Precolumbian Inca textiles, the designs of which are usually geometric and abstracted, they do appear regularly in viceregal textiles and should be understood as uniquely Andean. Indeed, the ñucchu flowers in the fragment’s innermost and outermost borders also appear on a variety of viceregal Andean tunics (including a miniature tunic in the Metropolitan’s collection, 2007.470). A viscacha can be found on the abovementioned mantle; birds of a similar style are also found on this mantle as well as on another lliclla in the Museum’s collection (08.108.10). Although viceregal authorities in Peru sometimes banned the depiction of animals on keros, silver objects, relief sculpture, wall painting, and textiles made by indigenous artists—such motifs were thought to encourage, and be evidence of, non-Christian religious practices—these regulations were neither uniformly followed nor enforced. The weaver of the textile from which this fragment was cut, like the weavers of the mantles featuring native fauna, does not appear to have feared such laws.

The fragment has two uncut edges and two cut edges. The two uncut edges, which make up one of the original corners of the textile, consist of an interlaced warp heading (the short edge) and the weft selvage (the long edge). In textile weaving, the warp is the set of lengthwise yarns held in tension on the loom and the weft consists of the yarns that are woven crosswise, over and under the warp yarns. Tapestry-woven textiles are weft-faced, which means that the weft yarns completely cover the warp yarns in the finished weaving. The missing weft yarns along the weft selvage of this fragment have exposed the warp yarns, giving us a clear sense of the textile’s structure. The edges of the tapestry would have originally been embroidered, as indicated by the two surviving sections of embroidery along the weft selvage.

This textile was probably made for a wealthy resident of one of viceregal Peru’s urban centers, perhaps Cusco. Its materials are typical of Andean weaving both before and after the Spanish invasion: cotton was used for the warp, and camelid fiber (spun from the wool of native Andean animals such as llamas, alpacas, vicuñas, and guanacos) was used for the weft. These materials indicate that the weaver had access to the products of both coastal Peru, where cotton was grown, and highland Peru, where camelids lived.

It is possible that the person or people who commissioned or first owned the tapestry had connections to both the indigenous cultures of Peru, as evidenced by the appearance of Andean flora and fauna, and also the newer, Europeanized cultures of the region, as evidenced by the imitation lace of the outer border and decorative elements of both the intermediate and the innermost borders. Indeed, the tapestry’s patron may have been a local indigenous lord, or an individual of mixed European and indigenous parentage. The incorporation of local and European motifs, along with the pronounced use of blue and purple, which was rare in Precolumbian Inca weaving, confirms the fragment as a product of viceregal Peru.

In this context, the lace design of the fragment’s outermost border is particularly intriguing. Lace, usually imported from Europe (Spain, Italy, and Flanders were all lace-making centers), was very popular in viceregal Peru. For example, a French traveler in the early eighteenth century described Peruvian women adorned with pearls, jewels, silks, and “a prodigious quantity of lace,” and paintings from the period show statues of the Christ Child dressed in sumptuous fabrics embellished with lace collars and cuffs. Although lace was widely available in Peru, imitation-lace designs were also woven into a variety of textiles, including large covers or hangings like the one from which this fragment was cut, as well as llicllas. These designs were not meant to be faithful copies of intricate lace patterns. Instead, the incorporation of lace-like designs was an aesthetic choice that added visual interest to the textile and evoked the luxuriousness and sumptuousness of actual lace. Furthermore, the viscachas and ñucchu flowers interspersed with the imitation lace on this fragment suggests a patron or owner who was eager to align him- or herself with both the native Andean and European strains of elite Peruvian culture.

The type of lace that the fragment imitates helps us to date the textile. The earliest surviving pieces of scallop-shaped lace date to the later sixteenth century, though the design reached the height of its popularity in the seventeenth century. We also see scalloped lace designs employed as borders in other media in seventeenth-century Spanish America: a ceramic basin, made in Puebla, Mexico around 1650 and now in the collection of the Philadelphia Museum of Art (1907-310), features a scalloped lace design around its rim, and several wall paintings found in churches in the Cusco region of Peru include painted scalloped lace borders.

It is likely that the weavers, potters, and painters who executed these designs adapted them from samples of actual lace. However, pattern books featuring designs for lace, strapwork, and other decoration also circulated widely in the period. In 1616, the Italian designer Isabella Catanea Parasole dedicated one of her books, which features a variety of scalloped lace designs, to Isabella of Borbón, the young wife of Prince Philip of Spain (he would become, in 1621, King Philip IV). A copy of this book is in the Museum’s collection (19.51, 1-46). The association of the book with the Spanish royal family makes plausible its circulation in Spain’s American realms, including Peru, and could therefore have been an additional—and prestigious—source for the imitation lace designs seen in this fragment.

Kate E. Holohan, Andrew W. Mellon Fellow, Department of the Arts of Africa, Oceania, and the Americas, 2016

References

Frézier, Amédée-Francois. Voyage to the South-Sea and along the Coasts of Chili and Peru in the years 1712, 1713, and 1714 (London: Printed for Jonah Bowyer, 1717), 219.

Gisbert, Teresa, Silvia Arze, and Martha Cajías. Arte textil y mundo andino. Buenos Aires: Tipográfica Editora Argentina, 1992

Jenks, Aaron A. and Seung-Chul Kim. “Medicinal plant complexes of Salvia subgenus Calosphace: An ethnobotanical study of new world sages,” Journal of Ethnopharmacology 146 (2013): 219-221.Further Reading

Cummins, Thomas B.F. Toasts with the Inca: Andean Abstraction and Colonial Images on Quero Vessels. Ann Arbor: The University of Michigan Press, 2002.

May, Florence Lewis. Hispanic Lace and Lace Making. New York: The Hispanic Society of America, 1939.

Flores Ochoa, Jorge A., Elizabeth Kuon Arce, and Roberto Samanez Argumedo. Qeros: Arte Inka en vasos ceremoniales. Lima: Colección Arte y Tesoros del Peru, 1998.

Padilla, Carmella and Barbara Anderson, eds. A Red Like No Other: How Cochineal Colored the World. New York: Skira, 2015.

Phipps, Elena. “Garments and Identity in the Colonial Andes.” In The Colonial Andes: Tapestries and Silverwork, 1530-1830, edited by Elena Phipps, Johanna Hecht, and Cristina Esteras Martín, 16-39. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2004.

—. “The Iberian Globe: Textile Traditions and Trade in Latin America.” In Interwoven Globe: The Worldwide Textile Trade, 1500-1800, edited by Amelia Peck, 28-45. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2013.

Speelberg, Femke. Fashion & Virtue: Textile Patterns and the Print Revolution, 1520-1620. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2015.