-

Object

-

Type of arts & crafts

-

MediumCamelid fiber

-

SizeW. 3 7/8 Г— L. 61 in. (9.8 Г— 154.9 cm)

-

Geography details

South America -

Country today

-

DateA.D. 200-700

-

CultureRecuay

-

Type of sourceDatabase “Metropolitan Museum of Art”

-

Fund that the source refers toMetropolitan Museum of Art

-

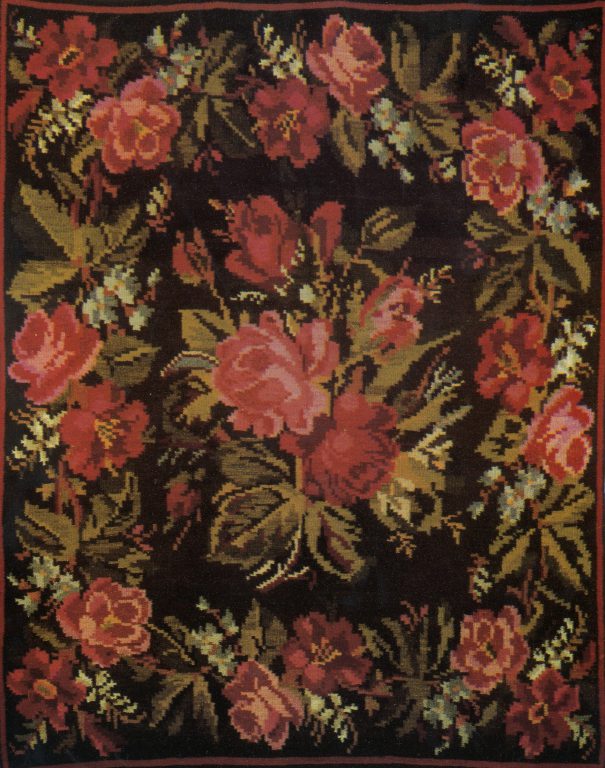

Ancient fabrics from the highlands of the Peruvian Andes rarely survive the adverse weather conditions that prevail there; this Recuay-style belt or chumpi, of extraordinary and complex elaboration, is a rare exception. The Recuay culture (A.D. 200–700) occupied the territory corresponding to the Callejón de Huaylas and the Callejón de Conchucos, a space between the Cordillera Negra and the Cordillera Blanca, in the North Central Andes of Peru. Its development was contemporary to the Mochica (also known as Moche) and Gallinazo cultures of the north coast; Cajamarca, from the northern highlands; and Lima, from the central coast, with whom they interacted from early times. Among these diverse cultures the Recuay stood out for the construction of mausoleum-like tombs and underground funerary galleries. They also created distinctive modeled ceramics, rich in ritual scenes. Some represent male and female characters who participate in rituals related to fertility; others depict battle imagery, including fortified spaces. Recuay artists also made monumental anthropomorphic lithic sculptures as part of a broader practice venerating ancestors, incorporating them into a community’s collective memory. The textile arts, in spite of the limited corpus, show a high technological development—one that distinguishes it from its contemporaries.

This belt was made in a technique known as triple-cloth, for which the weaver uses camelid fiber threads in three colors: red, yellow and green, which were harmoniously combined in the execution of each motif, which in turn were distributed symmetrically along its length. Two general types of images are projected through the intertwined threads of this belt: one is a serpentine, bi-cephalic creature; the other is identified as a Moon Animal, also known as a Recuay Dragon, a mythological figure found in both highland and coastal art during the first millennium, and is especially notable in Mochica iconography. Three types of double-headed serpentine beings are distinguished in the belt, and these designs appear at the ends. Two Moon Animals appear in the center of the belt. The weaver presents us with a fairly stylized and minimalist image of this mythological being, one that highlights two facial features: its prominent mouth with serrated teeth, and a concentric eye, from which a serpent’s head emerges.

Recuay potters modeled and painted their ceramics with great detail, providing a view of how such belts would have been worn. Male and female figures are clearly distinguished by their clothing: women wear dresses (aksu in Quechua) with a checkerboard decoration, secured at the shoulder by large metal pins, or tupus; around the waist they wear a wide belt. The ensemble is complemented by a cloth used to cover the head. Their bodies assume the shape of a vessel, or they are portrayed carrying them on their backs. Such vessels contained chicha, an Andean drink made from fermented corn and consumed during ceremonies. Belts, particularly those with motifs of mythological beings such as those mentioned above, were markers of high social status. Not simply functional accessories, they denoted power and hierarchy. The importance of this type of belt continued into the time of the Inca Empire (A.D. 1470–1532). The chronicle of the early 17th century Mercedarian friar Martín de Murua notes that during the corn harvest the coyas, wives of the Inca, wore a belt that they called sara (corn). The four-part rhombus on the sara belts denoted Tahuantinsuyo (also spelled Tawantinsuyu, literally “four parts joined together”), the name the Inca gave their empire.

Arabel Fernández, Andrew W. Mellon Foundation Conservation Fellow, 2020

References

Castro de la Mata, Pamela, and María Inés Velarde. “La tumba de la una mujer de élite Recuay.” In Señores de los reinos de la luna, pp. 262–265. Compl. Krzysztof Makowski. Lima: Banco de Crédito del Perú, 2008.De Murua, Martín. Historia del origen y genealogía real de los reyes Inca del Perú (1611). Ed. Constantino Bayle. Biblioteca Missionalia Hispánica. Madrid: Instituto Santo Toribio de Mogrovejo, 1946.

Eisleb, Dieter. Altperuanische Kulturen Recuay IV. Berlin: Staatliche Museen Preussischer Kulturbesitz, 1987.

Lau, George. “The Recuay Culture of Peru’s North-Central Highlands: A Reappraisal of Chronology and Its Implications.” Journal of Field Archaeology, vol. 29, N 1-2 (Spring 2002–Summer 2004), pp. 177–202, 2004.

Lau, George. “On Textiles and Alterity in the Recuay Culture (A.D. 200–700), Ancash, Peru. In Textiles, Technical Practice, and Power in the Andes, Denise Arnold Penny Dransart, eds., pp. 327–344. London: Archetype, 2014.

Mackey, Carol J., and Melissa Vogel. “La luna sobre los Andes: Una revisión del Animal Lunar.” In Moche: Hacia el final del milenio. Actas del Segundo Coloquio sobre la cultura Moche, pp. 325–342. Trujillo, 1 al 7 de agosto de 1999. Ed. Santiago Uceda y Elías Mujica. Trujillo and Lima: Universidad Nacional de Trujillo y Pontificia Universidad Católica del Perú, 2003.

Oakland, Amy, and Arabel Fernández. “Tejidos Huari y Tiwanaku: Comparaciones y contextos.” Boletín de Arqueología PUCP No. 4, pp. 119–130, 2000.

Porter, Nancy. “A Recuay Style Painted Textile.” In Textile Museum Journal, No. 31, pp. 71–81, 1992.

Proulx, Donald. “Territoriality in the Early Intermediate Period: The Case of Moche and Recuay. Ñawpa Pacha vol. 20, pp. 83–96, 1982.

Wegner, Steven. Iconografías prehispánicas de Ancash. Cultura Recuay, Tomo 2. Ed. Jorge Luis Puerta. Huaraz and Lima: Consorcio Recursos-Technoserve; Asociación Ancash, 2011.