-

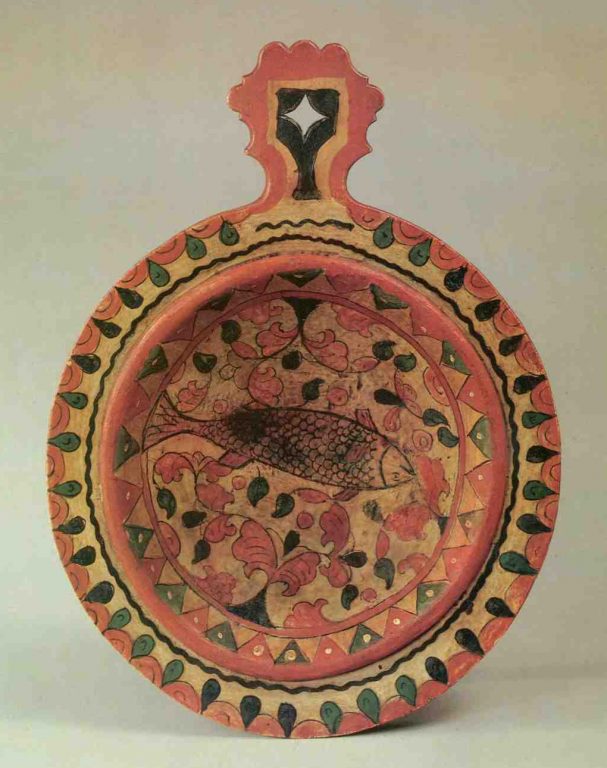

Objecttableware: Dish

-

Type of arts & crafts

-

MediumHard-paste porcelain painted with cobalt blue under transparent glaze

-

SizeOverall, irregular diameter (confirmed): 1 3/4 x 13 x 13 1/4 in. (4.4 x 33 x 33.7 cm)

-

Geography details

Italy -

Country today

-

Dateca. 1745-50

-

Type of sourceDatabase “Metropolitan Museum of Art”

-

Fund that the source refers toMetropolitan Museum of Art

-

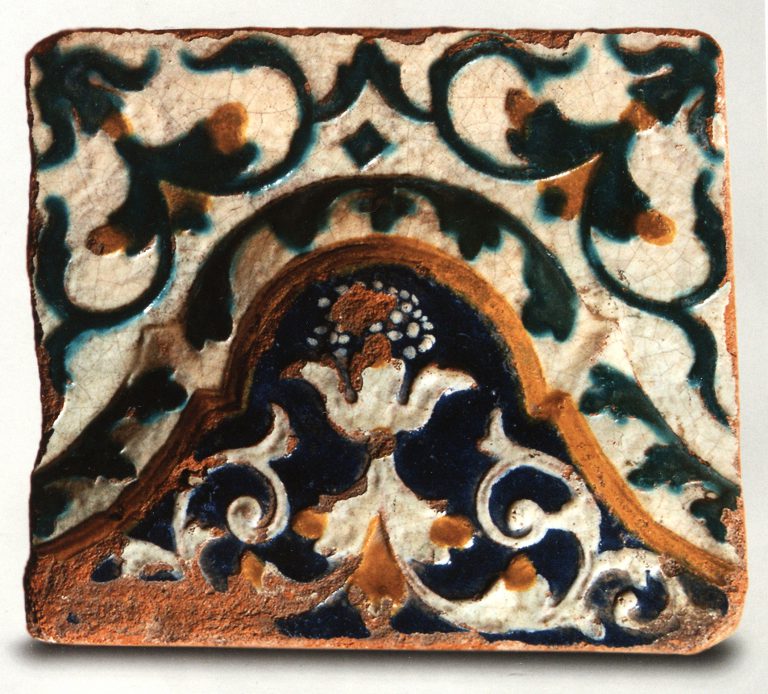

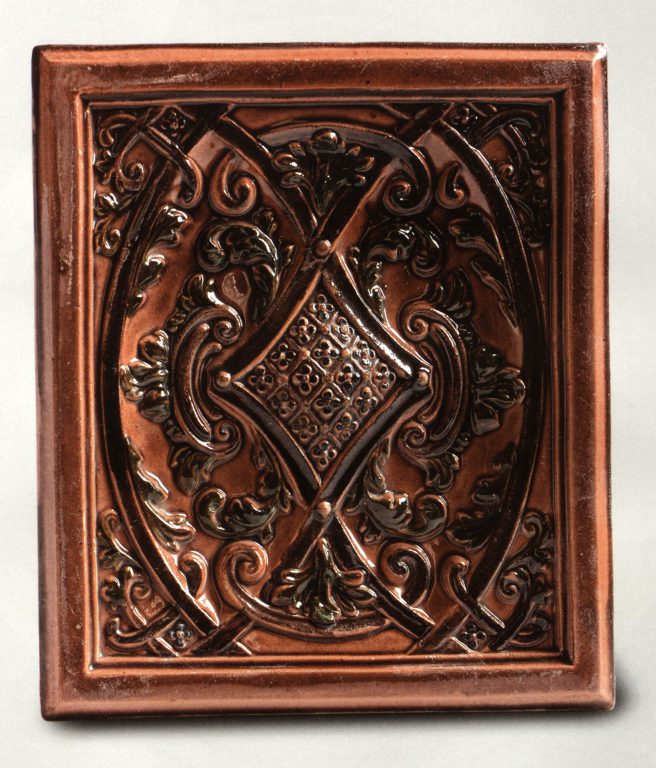

The Carlo Ginori factory, founded at Doccia outside of Florence in 1737, developed a notably wide repertoire of decorative techniques for its wares. Unusually, many of these techniques not only were distinct from one another but were in use more or less simultaneously, which speaks to the factory’s artistic ambitions. A number of these styles practiced at Doccia were unique to the factory, and the most extraordinary involved the use of stencils by which the decoration was applied. This technique became known as a stampino, though the term was not used in the eighteenth century,[1] and the stenciled designs were always executed in cobalt blue, as seen on this dish. Due to the high-firing temperature of cobalt oxide, it could be applied to the biscuit porcelain (fired but not glazed) and then fired at the same time as the transparent lead glaze that covered it, which reduced the total number of firings per object. Furthermore, the use of stencils meant that a relatively unskilled painter could apply the decoration, which was particularly useful at the Ginori factory during its early years when it was establishing its labor force.[2]

The stencils employed for the decoration were made from either paper, parchment, or a thin sheet of copper[3] with the form of the object dictating the material of the stencil. Dishes and plates decorated a stampino commonly follow a standard formula that included a spray of flowers in the center with a surrounding border decoration composed of floral motifs usually linked by C-scrolls. Documents from that time period indicate stenciled motifs were inspired by real flowers, as a letter dated to 1755 identifies a book with flowers that could be copied for copper stencils.[4] The complexity of the stenciled designs varied, and numerous small dishes were produced in which both the borders and central decoration consisted of simple floral motifs assembled in spare compositions.[5] In contrast, the Museum’s dish is one of the most elaborate of the stenciled works produced at the Ginori factory, with an unusually dense border design and a more complex central composition. The components of the border pattern are very similar to those found on several Ginori dishes but do not appear to be identical,[6] suggesting that as stencils wore out new ones were made based upon the earlier models, however, with inevitable slight variations occurring.

It is easy to imagine that the use of a simple decorative technique at Doccia might have been confined to objects to which stencils could be easily applied, such as dishes or plates, or to modest works for which the cost of polychrome decoration could not be justified. Clearly, however, the Ginori factory did not regard a stampino decoration as artistically inferior, and a variety of ambitious objects, including large, two-handled covered pots,[7] coffeepots,[8] baskets,[9] and tureens with stands,[10] were decorated in this manner and attest to the perceived desirability of this particular style.

The underside of the Museum’s dish is marked with the dome of the Florence Cathedral, also in underglaze blue, which is the same mark often found on the Medici porcelain produced in Florence approximately 170 years earlier (see 17.190.2045). While the soft-paste porcelain made in the Medici workshops during the late sixteenth century was a short-lived venture, it was one of the most technically and artistically challenging undertakings of the court under Francesco I de’ Medici (1541–1587), and Carlo Ginori’s (Italian, 1702– 1757) choice of this same mark can only be interpreted as his affirmation of the significance of his own ceramic accomplishments at Doccia. The blue-and- white color scheme of a stampino decoration recalls that of Medici porcelain, which is rooted directly in the Chinese porcelain that defined ceramics of the highest refinement in the European mind during this period. While the motifs chosen for both the Medici porcelain and Ginori’s a stampino wares were European in character rather than Chinese, the choice of cobalt-blue decoration at Doccia can be read as a deliberate link to Chinese porcelain and to the Medici’s attempts to re-create it. It is likely that Ginori regarded the dome mark as conferring a kind of legitimacy to his young ceramic enterprise, while simultaneously suggesting a continuity of inventiveness within Florence’s long-established and rich artistic tradition.

Footnotes

1 One of the terms for this technique that appears to have been used at the time of manufacture is a stampa (Biancalana 2009, p. 146), but the style may have been known simply as blau a fiori (with blue flowers; see Alessandro Biancalana in “Victoria and Albert Museum Collection” 2013, pp. 50–51, nos. 25, 26).

2 Biancalana in “Victoria and Albert Museum Collection” 2013, pp. 50–51.

3 Leonardo Ginori Lisci in Twilight of the Medici 1974, p. 432, no. 257.

4 Biancalana 2009, p. 147.

5 For example, see Biancalana in “Victoria and Albert Museum Collection” 2013, pp. 50–51, nos. 25, 26.

6 See the dish illustrated in Biancalana 2009, p. 147.

7 Agliano 1999, p. 22, fig. 2; Christie’s, Genoa, sale cat., June 19–20, 2000, no. 377 (sale held at Proprieta Galletto, Genoa).

8 British Museum, London (1914,0713.1); Bonhams, London, sale cat., July 6, 2010, no. 38.

9 Mottola Molfino 1976–77, vol. 1, no. 404.

10 Collezione Cagnola 1999, p. 296, no. 317.