-

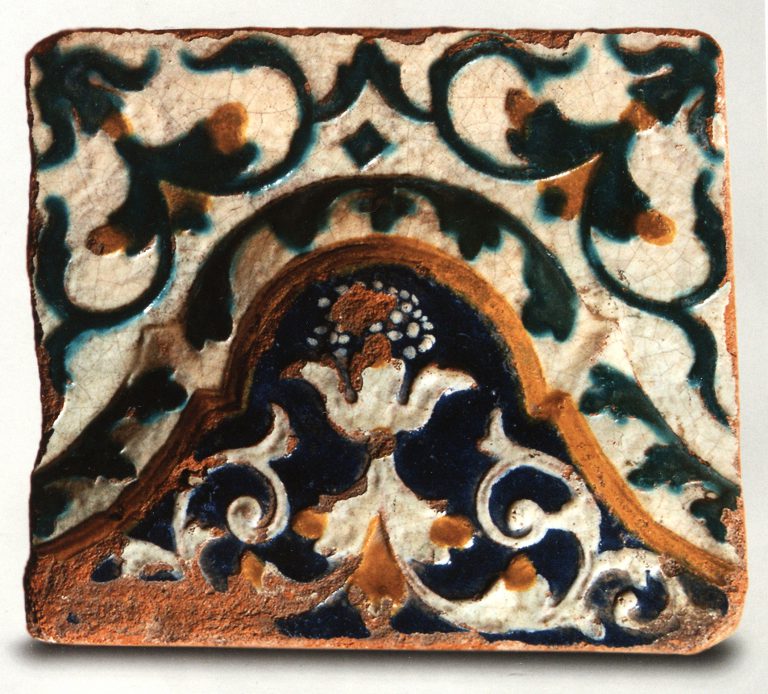

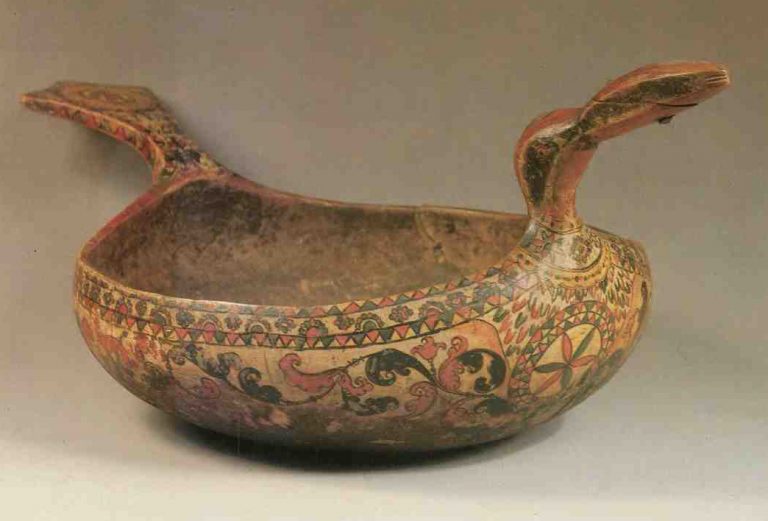

Objecttableware: Dish

-

Type of arts & crafts

-

MediumSoft-paste porcelain decorated in underglaze blue

-

SizeOverall, irregular diameter (confirmed): 2 1/4 Г— 13 3/16 Г— 13 1/8 in. (5.7 Г— 33.5 Г— 33.3 cm)

-

Geography details

Italy -

Country today

-

Dateca. 1575-80

-

Type of sourceDatabase “Metropolitan Museum of Art”

-

Fund that the source refers toMetropolitan Museum of Art

-

The soft-paste porcelain objects produced by the Medici workshops in Florence during the last quarter of the sixteenth century represent the first successful attempts at fabricating porcelain in Europe.[1 The ceramic body made by the Medici potters was an artificial porcelain, lacking the essential ingredients of true porcelain, as found in the Chinese porcelains prized in fifteenth-and sixteenth-century Europe. However, the hard, white Medici porcelain simulated Chinese porcelain, even if the former was composed of elements that were more closely related to the composition of early twelfth-century fritware ceramics produced in the Near East.[2] Chinese porcelains were valued for the whiteness of the clay body, the intense blues of the cobalt decoration, their translucency, as well as their durability, and the Medici collections were particularly rich in porcelains imported from Asia.[3] Cosimo I de’ Medici (1519–1574) must have had the goal of imitating Chinese porcelain when he established a ceramic workshop in the Casino di San Marco in Florence in the late 1560s; however, porcelain was not successfully produced until shortly after his death in 1574.[4] The oft-quoted observation of a Venetian ambassador to Florence in 1575 indicates that porcelain was being manufactured by that date: “Grand-Duke Francesco de’ Medici has found the way of making Indian [i.e., Asian] porcelain, and in his experiments has succeeded in equalling its quality—its transparency, hardness, lightness, and delicacy; it has taken him ten years to discover the secret, but a Levantine showed him the way to success.”[5] The reference to the role played by a potter from the Levant or Eastern Mediterranean may explain the similarity of the composition of the Medici porcelain to other ceramic bodies produced in this region, which were also intended to imitate Chinese porcelain.

Soft-paste porcelain was produced in the Medici porcelain workshops from 1575 to about 1587, the same year Francesco I de’ Medici died, though it is possible that production continued on a much-reduced basis until around 1620.[6] While documents indicate Medici porcelain was made in sufficient quantity to allow approximately 300 pieces to be recorded in the Medici collection in the early eighteenth century,[7] there are only around sixty to seventy pieces known to have survived today.[8] As writers have indicated, the experimental nature of the Medici enterprise is apparent in the surviving pieces.[9] Technical flaws, from slightly warped forms caused by the high heat required to fire the porcelain to blurred painted decoration where the cobalt has slipped, are common, yet it is easy to imagine the delight and admiration these objects must have inspired when they were made. Marks found on most surviving pieces of Medici porcelain suggest its status, as most display the renowned dome of Florence’s cathedral with the letter F below, presumably referring either to Florence or, less likely, to Francesco, and at least four pieces are marked with the six balls of the Medici coat of arms, the initials of Francesco’s name and title, or with both.[10]

The Museum’s large dish is exceptional in several ways. It is one of two pieces of Medici porcelain marked with the balls (or palle) of the Medici arms containing Francesco’s initials and his title cited above, though the letters on three of the palle are faint to the point of illegibility. More significantly, it is the only known piece to be marked with the grand ducal crown above the palle, making it tempting to interpret the elaborateness of the mark as an indication of the justifiable pride taken in its creation.

The ambitiousness of the dish is evident in the painted decoration. The central scene depicts the biblical King Saul falling upon his sword, his armor-bearer stabbing himself, and a townscape in the distance. The figurative scene is encircled by grotesque decoration that incorporates four female figures, fantastic birds, and half-human creatures. The outer rim of the dish is also painted with grotesque decoration that includes half-human creatures, masks, swags, and four cameo-style portrait heads. The organization of the dish’s grotesque decoration provides a subtle visual rhythm to the composition, which is executed with a sureness and lightness of touch. Derived from a print by painter and engraver Hans Sebald Beham (German, 1500–1550), the central scene has been described by Alan P. Darr as the only two-figure narrative composition found on a Medici porcelain,[11] thus exhibiting a degree of complexity and ambition notable for an experimental and short-lived ceramic enterprise. He has also suggested that the depiction of King Saul was intended to offer a parallel to the life of Cosimo, who died shortly before the dish was made, as both rulers were distinguished by their military and political successes, as well as their bravery.[12]

The technical challenges inherent in firing Medici porcelain, and especially an object of this scale, are evident in the faint slope to the rim, in the slight warping seen throughout, in the blurring of some of the cobalt decoration, and in the areas where the glaze has bubbled to a certain extent, but this dish nevertheless is a remarkable artistic achievement, realized in the new medium of porcelain. Further developments in the production of porcelain in Europe were not to take place for around another one hundred years, nor was Medici porcelain an influence on those potters working in France during the late seventeenth century. Without the patronage of Francesco, production of Medici porcelain ceased and escaped artistic and collecting attention until the late 1850s, when the art dealer Alessandro Foresi recognized a ceramic flask as a piece of Medici porcelain.[13] Foresi’s publication in 1859 regarding his discovery ignited a keen interest in Europe’s first porcelain, which has persisted to this day.[14]

Footnotes

1 Documentary evidence reveals there were experiments to make porcelain undertaken elsewhere in Italy earlier in the sixteenth century, but no surviving objects can be linked to these efforts; Thornton and T. Wilson 2009, vol. 2, p. 694.

2 The composition of the Medici porcelain body has been described as “white clay from Vicenza, fine white sand, powdered rock crystal and marzacotto (sand, salt, and calcinated wine dregs)”; Alan P. Darr in Darr, Barnet, and Bostrom 2002, vol. 1, p. 226.

3 The Medici collections included more than a thousand pieces by 1590; Thornton and T. Wilson 2009, vol. 2, p. 694.

4 Useful summaries of the history of Medici porcelain are found in T. Wilson 1987, pp. 157–58; Hess 2002, pp. 198–203; Thornton and T. Wilson 2009, vol. 2, pp. 694–99.

5 Thornton and T. Wilson 2009, vol. 2, p. 694.

6 T. Wilson 1987, pp. 157–58.

7 Spallanzani 1990, p. 317.

8 Differing numbers of surviving pieces of Medici porcelain have been published, and a definitive list does not exist to the author’s knowledge.

9 See, for example, Darr in Darr, Barnet, and Bostrom 2002, vol. 1, p. 226.

10 Le Corbeiller 1988, p. 125.

11 Darr in Medici, Michelangelo 2002, p. 251.

12 Ibid.

13 See Le Corbeiller 1988, p. 119.

14 Foresi 1859/1869.