-

Object

-

Type of arts & crafts

-

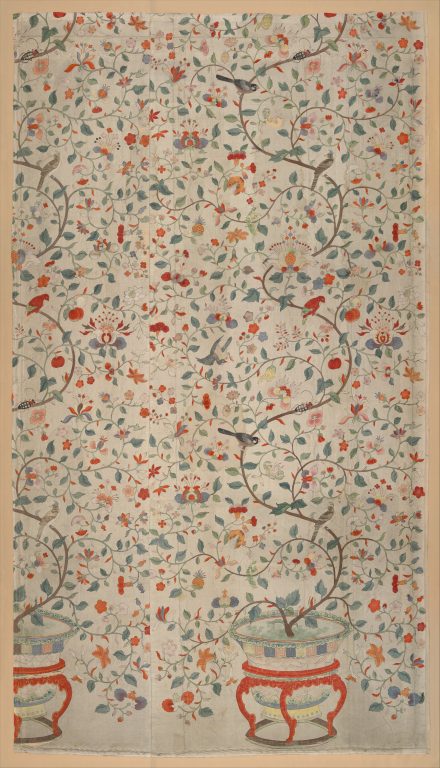

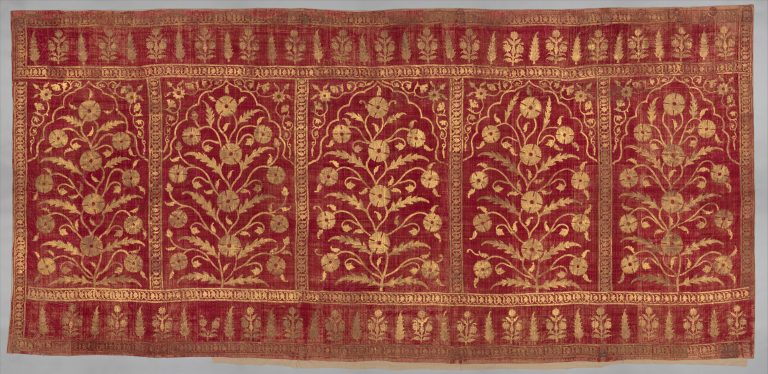

MediumSilk taffeta, painted and printed

-

Size78 x 43 in. (198.1 x 109.2cm)

-

Geography details

China -

Country today

-

Datelate 18th century

-

Type of sourceDatabase “Metropolitan Museum of Art”

-

Fund that the source refers toMetropolitan Museum of Art

-

The Chinese produced both painted wallpaper and painted silk wall hangings for export during the eighteenth century, and the workshops that made these wall coverings may have used the same patterns for both techniques. Silk wall coverings accounted for a very small percentage of the textiles exported from China to the West.¹ Along with the painted papers, however, their influence on the perception of chinoiserie in Europe is probably disproportionate to the actual number produced, as these wall coverings became closely associated with the invention of the “Chinese room,” an essential feature of European country houses and retreats.²

Painted pictorial wall decorations were entirely new products developed specifically for the European export market. Nothing like them were used in domestic Chinese interior decoration. The antecedent may have been the Chinese practice, noted by early travelers, of using monochrome paper coverings on their interior walls to create the effect of a uniformly white wall, without other decoration.³ Painted silk may have been used as a substitute for paper in the eighteenth century, as suppliers had a difficult time manufacturing enough paper to meet the requirements of European clients. In 1759 one such customer, Emily Lennox (1731–1814), great-granddaughter of Charles II of England and wife of James Fitzgerald, Earl of Kildare (1722û1773), commissioned her husband to buy her 150 yards of painted taffeta for bedroom furnishings while he was in London. Although the acquisition of this amount in a single pattern was said to be impossible, he finally succeeded, and according to Emily the painted “Indian” silk was only slightly more expensive than a silk damask available in Dublin, and infinitely more attractive.⁴

Paper hangings depicting garden scenes with flowering trees that grow from large Chinese vessels resting on decorative stands are preserved in several German and English collections.⁵ This painted silk also appears to be influenced by Indian chintz palampores, with their delicate meandering branches bearing a variety of fruits and flowers and populated by assorted small birds and insects. Here the regular meander and the delicacy of the design are closer to the dress silks of the later eighteenth century than to the more regimented garden scenes of the wallpapers. It is a charming hybrid of the Chinese and Indian motifs that continued to be popular into the late eighteenth century.

[Melinda Watt, adapted from Interwoven Globe, The Worldwide Textile Trade, 1500-1800/ edited by Amelia Peck; New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art; New Haven: distributed by Yale University Press, 2013]

1. See Jolly, “Painted Silks from China,” p. 167. This type of export textile may have begun as a luxury good acquired by private individuals in the trade, then presumably made on a commercial scale once they had achieved a certain degree of popularity.

2. Clunas et al., Chinese Export Art and Design, p. 114; Jolly, “Painted Silks from China,” p. 167.

3. Clunas et al., Chinese Export Art and Design, p. 112.

4. Tillyard, Aristocrats, pp. 154 – 55.

5. See Wappenschmidt, Chinesische Tapeten für Europa, pl. 10, figs. 89 – 91.