-

Objectfurniture, chests, stoves: Petaca

-

Author of the objectUnknown

-

Type of arts & crafts 1

-

Type of arts & crafts 2

-

MediumRattan structure covered with leather, embroidered with agave fiber and lined with fabric; forged, chased and openwork iron lock and hardware

-

Size18 7/8 Г— 24 3/4 Г— 17 3/4 in. (47.9 Г— 62.9 Г— 45.1 cm)

-

Geography detailsMade in

Central&North America -

Country today

-

Dateca. 1772

-

CultureNew Spain (Mexico)

-

Type of sourceDatabase “Metropolitan Museum of Art”

-

Fund that the source refers toMetropolitan Museum of Art

-

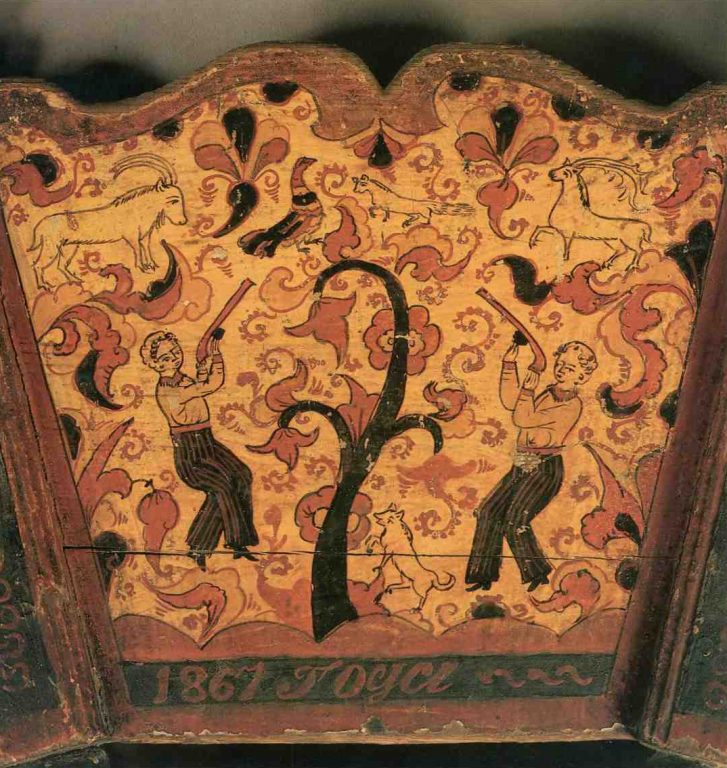

This embroidered leather chest (petaca) from 18th-century New Spain is among the finest and best preserved examples among the handful that survive. It is of exceptional historical importance as the only work of its type whose date and place of origin can be reliably established on the basis of documentation.

The Spanish word petaca, derives from the náhuatl petlacalli, a type of covered storage basket. Like Aztec petlacalli, the underlying structures of New Spanish petacas are woven like baskets. In imitation of chests imported from Spain, they are covered in leather and fitted with forged iron hardware. Local artisans in Mexico mastered Spanish leatherworking techniques and often adopted styles of ornamentation that were rooted in the Hispano-Islamic traditions of Andalucia. The finest petacas feature a type of embroidered decoration known as piteado, executed in pita or ixtle (thread made from maguey fiber). This example is unique among known New Spanish petacas in its use of multicolored embroidery.

Petacas were made for the safe storage and transport of valuables, especially clothing and other textiles. They frequently draw upon the same decorative repertory of human, animal, and floral motifs found in other luxury items made for domestic use in New Spain. This example features a conspicuous iron lock and is embellished with figural motifs that evoke elite tastes and privileges, leisure activities, and courtship rituals. The petaca is associated with a category of artworks from Mexico linked to the tornaviaje, that is, the return voyage to Spain. This group includes not only New World exotica prized by European elites, but domestic furnishings and luxury goods that were taken to Spain for personal use by returning merchants, ecclesiastics and colonial officials. Like most surviving petacas, the present one was preserved in a European collection, suggesting that its owner may not have been a permanent resident in Mexico, but a Spaniard who returned to his native country after living and prospering abroad. By virtue of its use as a travel chest, the petaca is explicitly connected to the mobility of people and goods, not only within Mexico, but in the larger Spanish world. This richly decorated chest and the valuables it once held under the protection of lock and key exemplified the wealth of New Spain and signaled the economic and social status of the person who owned it.