-

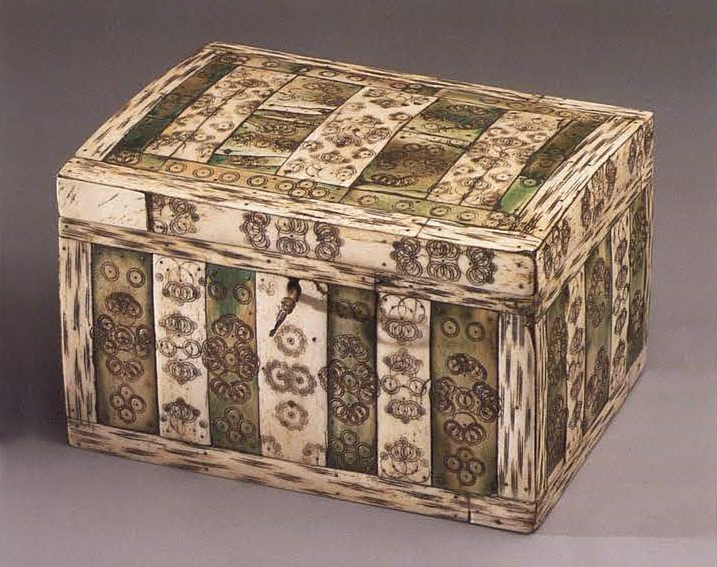

Objectinterior decoration: Casket

-

Type of arts & crafts

-

MediumSatin worked with silk and metal thread, seed pearls; tent, satin, couching, Ceylon, detached needlepoint variations, knotted pile, knots, and crochet stitches; needle lace, metal bobbin lace; wood frame, silk lining, carved wooden feet

-

SizeOverall: 8 Г— 16 Г— 14 1/2 in. (20.3 Г— 40.6 Г— 36.8 cm)

-

Geography details

United Kingdom -

Country today

-

Date1670s

-

Type of sourceDatabase “Metropolitan Museum of Art”

-

Fund that the source refers toMetropolitan Museum of Art

-

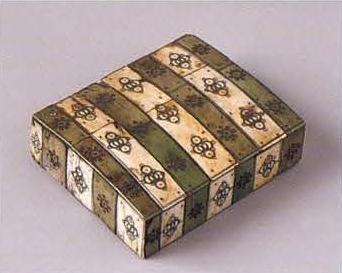

This casket, the largest in the Metropolitan Museum’s collection of embroidered boxes, contains a multitude of objects, from glass bottles, which were typically fitted into boxes of the period, to a large array of sewing implements and materials, including 25 paper thread winders made from folded playing cards, several ivory thread winders, a bodkin, three ivory embroidery tools, a spool of gold filé thread, a silk tassel, several loose skeins of silk thread, a silk needle case, and a piece of detached buttonhole stitch fabric. Some of the objects clearly do not match the casket’s seventeenth-century date. Thread, both dyed silk and metal varieties, was purchased by weight, and the number of objects devoted to the organization of threads speaks to the value of this material. Decorated boxes intended to store sewing implements, among other things, were known on the Continent as well as in England; several seventeenth-century Dutch cushion-shaped containers survive, and seventeenth-century genre paintings confirm their practical use as supports for sewing.

The completion of a decorated casket or cabinet would have been considered the culmination of a young woman’s education in needlework skills, and a few boxes have survived that can be firmly attributed to schoolgirls. Martha Edlin’s dated embroidered objects form the most complete record we have of one person’s output in the seventeenth century (Victoria and Albert Museum, London), although professional contributions at any point in the work would certainly have been possible. The exuberance of the decoration and the rather indiscriminate combination of materials and techniques suggest that this casket is the work of an amateur. Contrast this with the cabinet illustrating scenes from the Life of Joseph (MMA, 39.13.3a-k), which was executed in a single technique (laid and couched silk) and precisely and evenly worked on all faces of the box. This casket also lacks the consistency of theme present on most cabinets; the top of the lid shows the meeting of King Solomon and the Queen of Sheba, whereas the side panels are apparently random combinations of motifs typical of the period: heraldic animals, a castle, and a fountain, all surrounded by oversized flora and fauna. It is possible that the embroidered panels of this casket may have been applied to the wood carcass at a date significantly later than the execution of the decoration. The carcass itself is too large for the embroidered panels; the gaps where the satin foundation fabric does not cover the wood are patched with more silk and disguised with metal bobbin lace. The color and style of the lining—green silk with a padded main compartment—differ from most other boxes of the seventeenth century as well. Another casket in the Lady Lever Art Gallery collection has a similar padded interior, but the silk lining is described as the typical salmon-pink color.

Nevertheless, this casket is important for its possible association with a mirror in the Metropolitan Museum’s collection (MMA, 39.13.2a). The back of the mirror frame is marked with the initials A.P. and the date 1672, and the casket contains thread holders or winders and a metal bodkin marked with the same initials. Both of these objects were in the collection of Percival Griffiths, and early scholars assumed that they were the work of the same maker. Although the mirror frame displays a more skilled and certain command of techniques and materials, it does contain some unusual elements, such as actual shells used in the decoration of the grotto. G. Saville Seligman and Talbot Hughes mentioned “Lady Ann Paulet, who was a very accomplished broiderer” in association with these embroideries, possibly referring to a lady-in-waiting to Queen Mary II (1662–1694), but no other evidence exists to support this attribution. The uncertain date of the construction of the casket, along with the survival of various tools and accessories, speaks to the continued significance of embroidery in the lives of women beyond the seventeenth century.

[Melinda Watt, adapted from English Embroidery from The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1580-1700: ‘Twixt Art and Nature / Andrew Morrall and Melinda Watt ; New Haven ; London : Published for The Bard Graduate Center for Studies in the Decorative Arts, Design, and Culture, New York, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York [by] Yale University Press, 2008.]