-

Objectfurniture, chests, stoves: Hip-joint armchair

-

Type of arts & crafts

-

MediumWalnut and elm, partly veneered and inlaid with different woods, ivory, bone (camel?) and pewter; covered in silk velvet not original to the armchair

-

Sizeh. 36 1/2 x w. 24 x d. 19 1/2 in. (92.7 x 61 x 49.5 cm)

-

Geography details

Spain -

Country today

-

Dateca. 1480-1500

-

Type of sourceDatabase “Metropolitan Museum of Art”

-

Fund that the source refers toMetropolitan Museum of Art

-

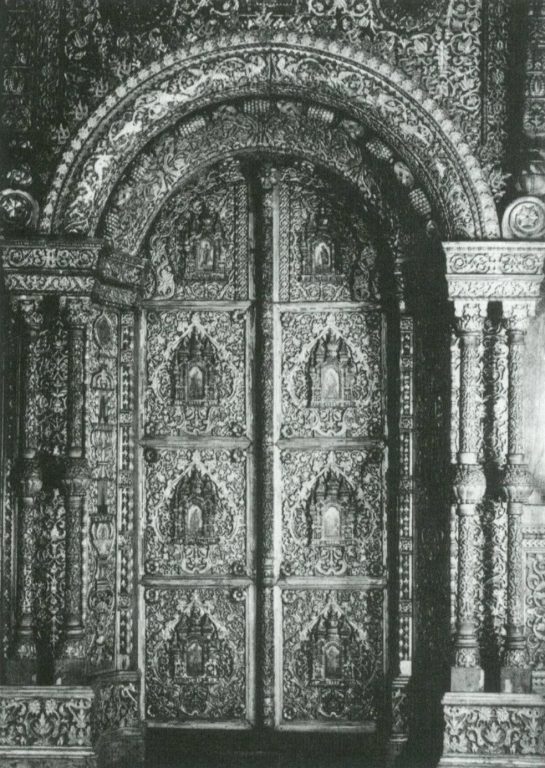

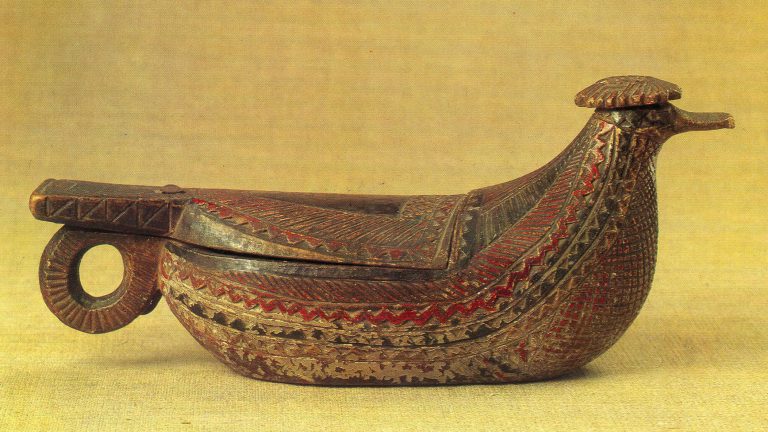

This armchair consists of four S-shaped supports on two runner-like stands. The disks that join two of the supports at front and two at back suggest that the chair can be folded up like a pair of scissors. This is not possible, however. The supports will collide above the turning point, allowing only a small degree of movement. This impractical arrangement can easily be explained by the chair’s derivation. It descends from the sella curulis, or curule chair, an ancient Roman folding seat used by consuls and high officials. In its elegant medieval interpretation, the throne-like chair—by then called a faldistorium—continued to symbolize secular power, and as the customary seat of the higher clergy, it also came to express the authority of the church.[1] The folding mechanism was eventually eliminated, and the place where the joint had been was marked with an ornamented disk.

By the late fifteenth century the seat and back of the curule chair were usually covered with a luxurious textile or embossed and stamped leather, and the frame was ornately inlaid and carved. Contemporary paintings suggest that the decoration on some examples may have reached a surreal level of exaggeration. The golden Throne of Scipio, seen in a cassone painting of 1490–1500 in the Courtauld Institute of Art Gallery, London, is embellished with cornucopias and lions’ paws.[2]

The precious tarsia a toppo marquetry on the frame of the Museum’s chair consists of tiny polygonal pieces of different colored woods, bone, and metal arranged in geometric patterns.[3] Some of the configurations, such as a minute square made up of nine even smaller squares, can be fully appreciated only with the aid of a magnifying instrument.[4] The “points” dependent from the legs of the Museum’s chair make the crescents that they form resemble Gothic ogee arches; however, the broken curves are also reminiscent of the Moorish arcades surrounding the Court of the Lions in the Alhambra at Granada and of the Moorish-Renaissance facade of the Palacio de Jabalquinto in Baeza of about 1490.[5]

The Spanish terms for the curule chair are sillón de cadera (hip-joint chair) and jamuga (saddle for a woman, or sidesaddle).[6] As the chair type spread throughout Europe and parts of Spanish America it acquired many other names. In the mid-nineteenth century, during the Renaissance Revival, it was known as a Dante or Savonarola chair. Possibly for this reason the present chair and three related examples in the Museum were mistakenly catalogued until recently as sixteenth-century Italian furniture.[7] Also evocative of Italy is the marquetry, which resembles twelfth-century Cosmati work[8] as well as lavoro alla certosina, a type of wood inlay very popular, especially in northern Italy, during the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries.[9] Nevertheless, it should be remembered that both of these inlay techniques reflect the influence of Islamic woodwork.

The most convincing reason for attributing the present chair to a workshop in Granada is the existence of a very similar chair formerly in the collection of Paul Almeida, Madrid.[10] The backrest, which retains its original leather cover, is decorated with an embossed Arabic inscription dedicated to the last Muslim sovereign of Granada, Muhammad XI, called Boabdil, who reigned from 1482 until his abdication after the battle of Lucena in 1492 (he died in 1538). It was therefore probably made before the sultan was forced into exile, leaving his beloved residence in Granada. The Alhambra court workshop possibly created that chair and all four of the Museum’s hip-joint chairs.

An origin in Granada may be supported by a fifteenth-century document that mentions a commission for three sillónes de cadera from Granada to be used in the Cathedral of Toledo.[11] (One of them is still kept in the cathedral treasury.) The fact that three chairs were ordered may indicate that they were used during the Mass at high church feasts, when two would have been placed on either side of the third, the bishop’s elevated chair, which would have been more elaborately upholstered and decorated than those of his concelebrants.

Hip-joint chairs remained accoutrements of the mighty throughout the 1500s, not slipping out of fashion for at least another century. Like Hispano-Moresque pottery, they may have been exported from Spain to Italy,[12] stimulating the production of less sophisticated inlaid chairs on the peninsula. A noblewoman is seen seated in a handsome example in a portrait now in the Metropolitan.[13] An etching that illustrates the abdication of control of the Netherlands by Emperor Charles V (1500-1558) in Brussels in 1555 shows hip-joint armchairs,[14] as does a portrait of the powerful archbishop of Canterbury Thomas Cranmer (1489-1556) ten years before he was burned at the stake.[15] A detailed list of property in the 1556 will of Sir John Gage of Firle Place in Sussex includes five Spanish-made chairs decorated with colored bone inlay.[16]

The ritual function of the sillón de cadera has remained alive in Spain until our own times. The Spanish king Juan Carlos I (b. 1938) and H. H. Shah Kerim Aga Khan (b. 1936) were seated side by side on two such inlaid throne-chairs on the occasion of the Aga Khan Award ceremony at the Al-hambra on 5 June 1990.[17]

[Wolfram Koeppe 2006]

Footnotes:

[1] Ole Wanscher. Sella Curulis, the Folding Stool: An Ancient Symbol of Dignity. Copenhagen, 1980.[2] John Morley. The History of Furniture: Twenty-five Centuries of Style and Design in the Western Tradition. Boston, 1999, p. 90, fig. 158.

[3] On this type of intarsia decoration, see the catalog entry for 45.39 and Antoine M. Wilmering. The Gubbio Studiolo and Its Conservation. Vol. 2, Italian Renaissance Intarsia and the Conservation of the Gubbio Studiolo. The Metropolitan Museum of Art. New York, 1999, p. 64, fig. 2-4, and p. 72.

[4] Identically fashioned squares decorate several other chairs. This suggests, but does not prove, that all of them originated in the same workshop. The squares on one chair in the Lemmers-Danforth Sammlung, Wetzlar, are illustrated close up in Wolfram Koeppe. Die Lemmers-Danforth-Sammlung Wetzlar: Europäische Wohnkultur aus Renaissance und Barock. Heidelberg, 1992, pp. 75-76, no. M8a, b.

[5] See Juan José Junquera y Mato. Spanish Splendor: Great Palaces, Castles, and Country Houses. New York, 1992, pp. 289, 279. For the Hispano-Moresque style in furniture, see José Ferrandis Torres. “Muebles hispanoárabes de taracea.” Al-Andalus 5 (1940), pp. 459-65.

[6] Martín Alonso Pedraz. Diccionario medieval español: Desde las Glosas Emilianenses y Silenses (s. X) hasta el siglo XV. 2 vols. Salamanca, 1986; for the etymology, see the excellent summary in Cybèle Trione Gontar. “The Campeche Chair in The Metropolitan Museum of Art.” Metropolitan Museum Journal 38 (2003), n. 38. See also Grace Hardendorff Burr. Hispanic Furniture from the Fifteenth through the Eighteenth Century. 2nd ed. The Hispanic Society of America. New York, 1964, fig. 11; and Andrew Ciechanowiecki. “Renaissance: Spain and Portugal.” In World Furniture: An Illustrated History, ed. Helena Hayward. New York, 1965, p. 62, fig. 191.

[7] Two chairs were acquired in 1945 (the present example and acc. no. 45.60.40a), and two entered the Metropolitan with the Robert Lehman Collection (acc. nos. 1975.1.1978,1979) in 1975. One example with a leather cover (45.60.40a) was published in Cybèle Trione Gontar. “The Campeche Chair in The Metropolitan Museum of Art.” Metropolitan Museum Journal 38 (2003), fig. 27, as having been produced about 1500 in Granada, a date and location originally proposed by the present author, on whose unpublished research notes in the files of the Department of European Sculpture and Decorative Arts, Metropolitan Museum, the Gontar attribution was based. On the Spanish origin of these and other inlaid hip-joint armchairs, see the comprehensive study in Wolfram Koeppe. Die Lemmers-Danforth-Sammlung Wetzlar: Europäische Wohnkultur aus Renaissance und Barock. Heidelberg, 1992, pp. 75-76, no. M8a, b, color ill. p. 172. For the two chairs from the Lehman Collection, see Wolfram Koeppe et al. Decorative Arts in the Robert Lehman Collection. The Metropolitan Museum of Art. New York, 2012, no. 159 and 160, p. 229-232.

[8] One of the most prominent examples is the episcopal throne in Santa Balbina in Rome; see John Morley. The History of Furniture: Twenty-five Centuries of Style and Design in the Western Tradition. Boston, 1999, p. 64, fig. 107.

[9] An example is illustrated in ibid., p. 102, fig. 174, and another is a chest in the Museum’s collection (acc. no. 07.97). A third is in the Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam (acc. no. BK-16629).

[10] Peter Dreyer brought this piece to my attention and made its examination possible in 1991. Two related chairs in the Lemmers-Danforth Sammlung, Wetzlar, have the same provenance; Wolfram Koeppe. Die Lemmers-Danforth-Sammlung Wetzlar: Europäische Wohnkultur aus Renaissance und Barock. Heidelberg, 1992, pp. 75-76, no. M8a, b, color ill. p. 172.

[11] Luis M. Feduchi. Estilos del mueble español. Madrid, 1969, p. 75, n. 37.

[12] Timothy Wilson. “Maioliche rinascimentali armoriate con stemmi fiorentini.” In L’araldica: Fonti e metodi, pp. 128-38. Ti con erre 18. Florence, 1989.

[13] Acc. no. 32.100.66; see Katherine Baetjer. European Paintings in The Metropolitan Museum of Art by Artists Born before 1865: A Summary Catalogue. New York, 1995, p. 38. For a portrait of Bianca Cappello, the second wife of Francesco I de’ Medici (r. 1574-87), by Alessandro Allori (1535-1607), standing next to a hip-joint chair with different inlay patterns, see Karla Langedijk. The Portraits of the Medici, Fifteenth–Eighteenth Centuries. 3 vols. Florence, 1981-87, vol. 1, pp. 317, 319, no. 11, fig. 12, 11.

[14] Enrico Castelnuovo. “Tapezzerie bellissime in figure.” In Gli arazzi del cardinale: Bernardo Cles e il Ciclo della Passione di Pieter Van Aelst, ed. Enrico Castelnuovo, Storia dell’arte e della cultura. Trent, 1990, p. 13, fig. 1.

[15] Anthony Wells-Cole. Art and Decoration in Elizabethan and Jacobean England: The Influence of Continental Prints, 1558–1625. New Haven and London, 1997, p. 37.

[16] Geoffrey Beard. Upholsterers and Interior Furnishings in England, 1530–1840. Bard Studies in the Decorative Arts. New Haven and London, 1997, p. 28. I thank Daniëlle Kisluk-Grosheide for bringing this to my attention.

[17] Connaissance des arts, no. 475 (September 1991), p. 7. I am most grateful to H.S.H. the late Princess Margarete of Isenburg-Birstein for steering my thoughts toward a possible Spanish origin for the chair type and for mentioning in 1985 the existence of several such armchairs at the Museo Arqueológico, Granada.