-

Object

-

Type of arts & crafts

-

MediumLampas, silk and metal thread

-

SizeL. 58 3/4 (with fringe) x W. 62 inches (149.2 x 157.5 cm)

-

Geography details

France -

Country today

-

Date1720s

-

Type of sourceDatabase “Metropolitan Museum of Art”

-

Fund that the source refers toMetropolitan Museum of Art

-

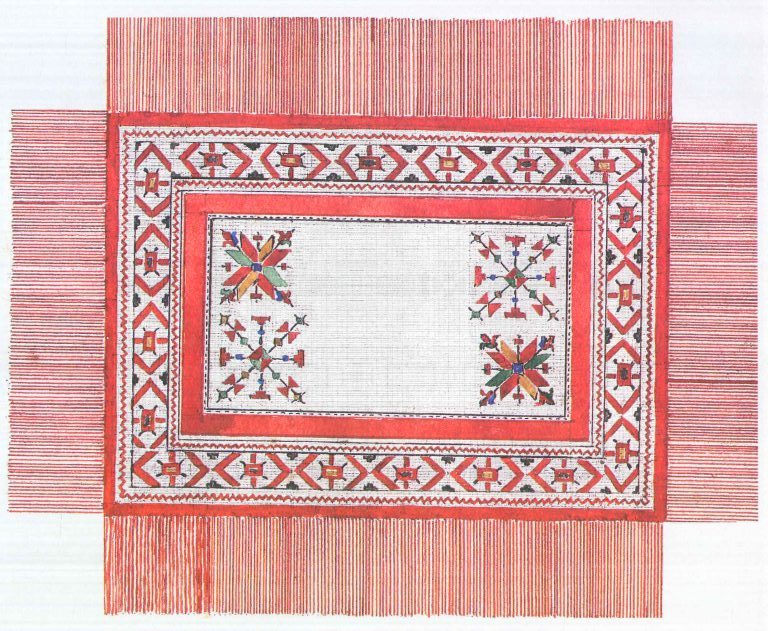

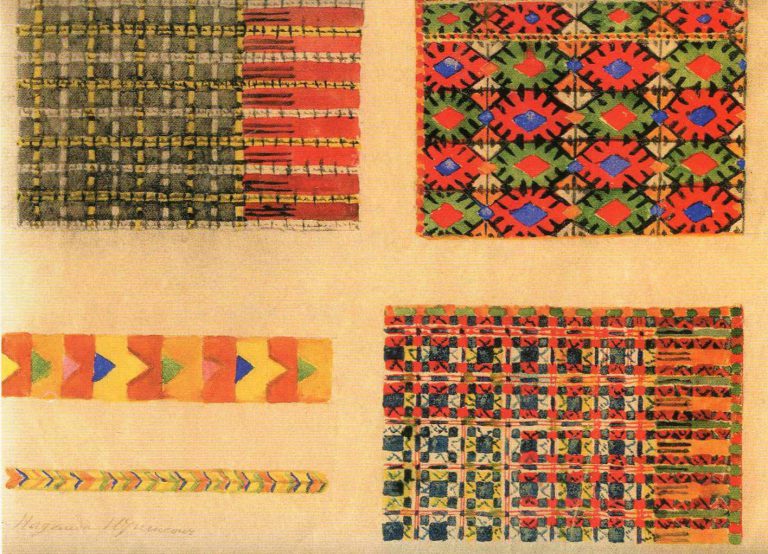

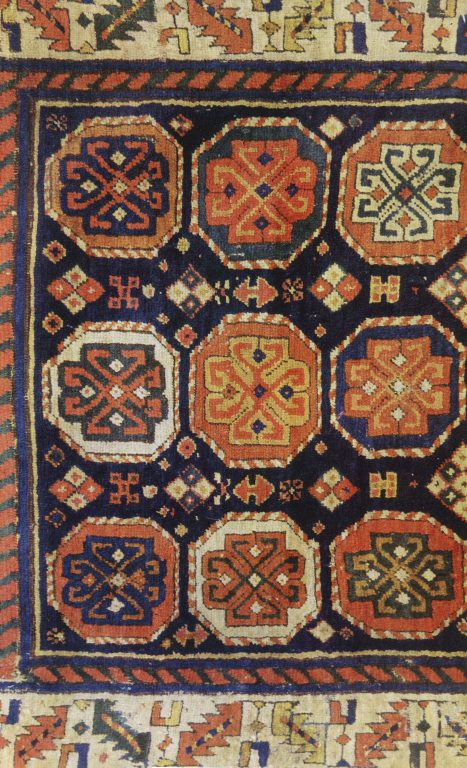

In Le dessinateur, pour les fabriques d’etoffes d’or, d’argent et de soie, a manual for the silk designer published in 1765, one of the textile terms included is persienne. It is described as a weave structure with characteristics that correspond to those of many so-called lace-pattern silks of the 1720s. The principal feature of this fabric was, according to the author, Antoine Nicolas Joubert de l’Hiberderie, the juxtaposition of two contrasting foundation weaves—a dark or boldly colored satin weave and a white plain weave—that were augmented by brocading in additional colors of silk and possibly one or more metallic threads.¹ It is unclear in Le dessinateur whether persienne was a purely technical term or whether it also described a style. In addition to the technical definition given in the 1765 publication, evidence that persienne referred to a style as well as a structure is provided by labels inscribed on the drawings of such designs dating between 1723 and 1730.²

The serrated leaves and rather stiff drawing of the flowers on the present silk piece reflect both Ottoman and Indo-Persian floral designs. In its weave, the silk adheres to the technical definition of a persienne, while suggesting a debt to the art and architecture of the Islamic world in its use of the mihrab-shaped compartments that frame the central plant motif. So, while this distinctive type of silk, made in the weaving centers of France, England, and the Netherlands, is now referred to as “lace patterned” owing to its lacy ribbonlike motifs, the eighteenth-century term might serve just as well.

This type of vibrantly colored floral silk was used in both men’s and women’s fashions, including a number of men’s banyans. That this textile was a product of European looms did not diminish the exotic properties that made it appropriate for leisure wear, just as the so-called bizarre silks were in earlier decades (see MMA 64.35.1).

These European silks also spawned Indian chintz designs that were created both for the European market, like a chintz panel in the Museum’s collection (see MMA 36.90.121), and for sale closer to the Indian subcontinent, such as a long cloth made for the Indonesian market in the Museum’s collection (see MMA 2011.44). The subdued monochrome palette of the chintz panel may have meant that it was intended for mourning wear, the colors of which gradually shifted from black to increasingly lighter shades of blue and the eventual addition of red during the period of observance.³ European fashions in silk design changed rapidly, so it is probably safe to assume that any chintzes made to imitate popular Western patterns were produced fairly quickly so as not to be outdated before they arrived in Europe. However, these patterns might have had a longer life span in markets in the East.

[Melinda Watt, adapted from Interwoven Globe, The Worldwide Textile Trade, 1500-1800/ edited by Amelia Peck; New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art; New Haven: distributed by Yale University Press, 2013]

1. See Leclercq, “From Threads to Pattern Composition, Technique, and Aesthetics,” pp. 139–54, 211–24.

2. Ibid., p. 139 n. 2.

3. See Gittinger, Master Dyers to the World, pp. 176–77, and fig. 150, a mourning wentke in blue and black in the Fries Museum, Leeuwarden, Netherlands (no. 1957-400). See also Hartkamp-Jonxis, Sitsen uit India/Indian Chintzes, pp. 84–85, a mourning wentke in blue with silver accents; and Crill, Chintz: Indian Textiles for the West, p. 103, no. 55, a wentke in black on white, also for mourning.